News analysis

Why we should not give up on local farms despite setbacks faced by the sector

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The buoyant appetite for high-tech farming was not to last, and the local farming sector has seen closures and falling output.

PHOTO: ST FILE

SINGAPORE – In February 2019, there was much fanfare when fish farm Barramundi Group launched its expanded nursery off Pulau Semakau.

The Republic was nurturing fertile ground (and waters) to propel local farming to greater heights, fuelled by a new target to produce 30 per cent of Singapore’s nutritional needs by 2030. More farms sprouted up, and the agri-tech sector was raring to go.

The buoyant appetite for high-tech farming, however, was not to last – and the local farming sector has since been gripped by closures and falling output.

Yet, Singapore cannot give up on trying to build up its local farming sector, as having a local buffer against supply shocks is non-negotiable.

This is especially so with climate change, geopolitical conflicts and animal disease outbreaks posing a constant threat to imported food supply – Singapore’s key strategy to safeguarding its food security.

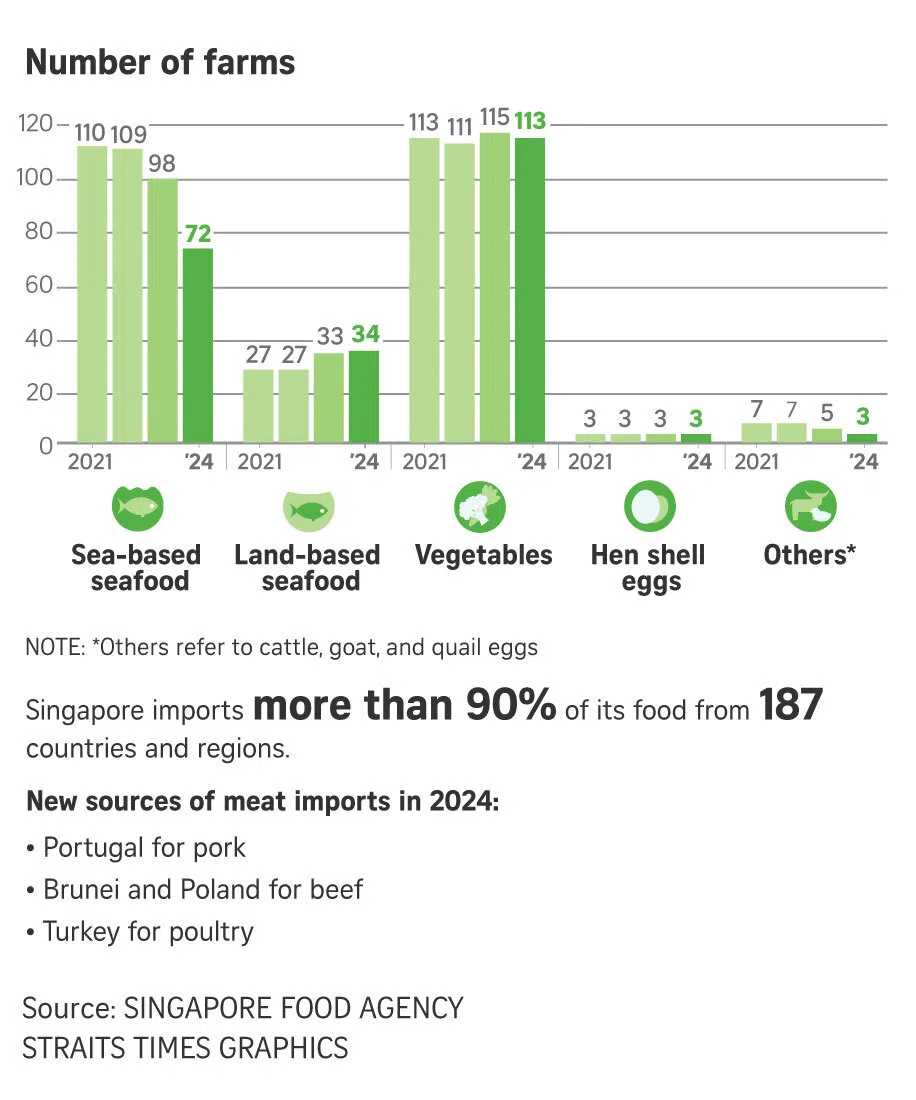

Even though Singapore is importing food from 187 countries and regions, it is not prudent to rely on just external sources when droughts and extreme weather can upend the world’s food bowls as climate impacts worsen.

On June 5, the national food statistics showed a drop in the output of vegetables and seafood from local farms

The country’s three egg farms, however, bucked the trend. These high-tech facilities produced 34.4 per cent of all eggs consumed in 2024, up from 31.9 per cent in 2023. This was due to the farms’ upgrades and operational efficiencies.

At the same time, about 50 per cent of bean sprouts consumed come from local farms, Singapore Food Agency (SFA) chief executive Damian Chan told the local media on May 29.

So, these successes give some hope that leafy greens and fish can turn the tide with time and effort.

In recent years, farms here have had to grapple with multiple setbacks – including animal disease outbreaks, soaring electricity prices and an investment winter.

Barramundi Group, for example, was hit by a fish virus outbreak in 2023 that grounded its commercial operations. It was also revealed that the group was making plans to exit Singapore

Singapore, which imports more than 90 per cent of its food, has already had a taste of such disruptions in imported food supply.

In early 2023, farms in Malaysia were inundated by floods, and the lower vegetable yields affected Singapore

In 2022, Malaysia imposed a chicken export ban

Back then, more than a third of Singapore’s chicken supply came from Malaysia. This resulted in higher chicken prices, and a number of small shops and hawkers decided to pause business as they were reliant on Malaysian poultry.

Mr Chan has outlined an overarching strategy to address farms’ pain points – from initiatives to ensure consistent sales to supplying a local pipeline of healthy baby fish.

This overarching plan is a step in the right direction, said experts, but they also stressed that the agri-food sector cannot skip getting the basic science of aquaculture and growing crops right.

High-tech farming is a nascent sector in Singapore and globally, and technologies used to increase productivity are not yet at a plug-and-play stage.

Local vegetable producer Artisan Green’s CEO Ray Poh said he approached this business cautiously to understand the levers that make farming work in the Singapore context.

“Some farms have approached (high-tech farming) from the engineering angle, but ultimately, without the foundational plant science knowledge, the systems are not optimised for plant health and growth,” he said.

Singapore has also made strides in ensuring that fish farming in the Strait of Johor north of the country, where dissolved oxygen levels are low and pathogen levels are high, can be more productive, by elevating farming practices in late 2024.

Under the plan, farmers are urged to use proper pellets instead of expired bread to feed fish, and must track nutrient levels in the water.

Professor Dean Jerry, director of the Tropical Futures Institute at James Cook University, Singapore, said: “Many farms do not purchase high-quality fish feeds matched to the requirements of the species farmed, so the fish are not growing at their best performance and there is a lot of wastage.”

He added: “Singapore waters are a hotbed of pathogens that, if not detected early, managed and eliminated from systems, can rapidly cause massive mortalities.”

It is clear that efforts are being made to help Singapore’s farms cope. But there are some pain points faced by local farms that recent initiatives do not address.

Agri-food consultant Lee Eng Keat suggested investing in infrastructure to reduce the distribution cost of produce, which is the expense incurred in getting fresh produce from the farm to consumers.

“Currently, much of this is undertaken through distributors and supermarkets. They charge a relatively high margin to take on this risk. Perhaps the Government can consider alternative models to better support farmers with the distribution cost,” he said.

Lack of adequate farming infrastructure is another challenge that existing plans do not flesh out.

Barramundi Group had cited the lack of infrastructure as a reason why it planned to exit the Singapore market. Transporting fish feed and equipment was challenging with no dedicated jetty for fish farmers to use.

But SFA said in 2024 that it is looking to improve fish farming infrastructure

Similar infrastructure problems exist in the Strait of Johor, where almost all of Singapore’s 72 at-sea farms are found. For one thing, most farms have to rely on diesel as they have no means of tapping electricity from the grid.

Several farms and experts have also called for shared post-harvest facilities.

Mr Poh said: “Stronger support through longer conditional land tenures, customised grants based on each farm’s performance and potential, and even favourable infrastructure rates through shared facilities can be considered.”

But helping farmers boost productivity to increase the supply of local produce is just one part of the picture.

On growing demand, the Singapore Agro-Food Enterprises Federation has brokered long-term contracts between a bloc of farmers and retailers, to ensure the continuous sale of marine tilapia and leafy greens.

But this can be scaled up with contracts with schools and the military, suggested Associate Professor Matthew Tan from the Singapore Institute of Technology.

Prof Tan – who chairs the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation’s Policy Partnership on Food Security for sustainable development in the agriculture and fishery sectors – also urged farms to align with retail partners, insurers and logistics players early to secure market access and reduce operational risks.

“A structured approach that combines innovation, prudent business management and environmental stewardship will be essential to avoid repeating such costly exits,” he said.