Embracing mother tongue, one book at a time: Reading clubs seek connection to culture

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Members of the Maya Illakiya Vattam, a Tamil reading club founded in 2019, sharing their thoughts during a reading session at Woodlands Regional Library.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

- Some reading clubs promote mother tongue languages and local literature, but face challenges attracting younger members.

- Reading clubs use various methods to boost interest, some with NLB's support.

- Experts emphasise accessibility, relevance, and integrating MTL into daily life to increase youth engagement in reading.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – On a Sunday evening at Woodlands Library, Ms Rama Suresh gathered with about 20 others to discuss The Goddess In The Living Room, a Tamil book by well-known local writer K. Kanagalatha highlighting the experiences of Singaporean Tamil women.

Beyond the usual conversation on the book’s themes, the highlight of the two-hour book club session was the chance to share her views directly with Ms Latha, who is also an associate editor at Tamil Murasu.

The Tamil-language reading club is among a small but determined group of book clubs here with outsized dreams of encouraging bilingualism and deeper ties to local culture through the mother tongue languages.

Their membership numbers may not be large, but they have found their niches. For example, the Maya Literary Circle is focused on showcasing Singaporean Tamil writers, while the Taxi Shifu and Friends book club was formed two decades ago to bring together fellow drivers and their friends.

Many of these clubs are content to carry on with their dedicated bases even as they contend with the challenges of recruiting younger members.

Ms K. Kanagalatha, 57, a two-time winner of the Singapore Literature Prize and associate editor at Tamil Murasu, at a reading session for the Maya Illakiya Vattam, a Tamil reading club founded in 2019.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

Ms Suresh, 47, herself an accomplished writer, founded Maya Literary Circle in 2019. The club has 25 members, mostly aged between 35 and 65.

The only regular young participant is her daughter Sadhana Suresh, 18, who helps with online publicity.

The Year 1 mass communications student at Republic Polytechnic said: “I don’t read Tamil books as much as English ones, but I like what my mum is doing, which is to bring recognition to local writers.”

For many members, passing on the love of Tamil literature to the next generation is easier said than done.

Ms Priya Rajiv, 44, a homemaker and Tamil literature graduate, said she enjoys the intellectual stimulation from the sessions but cannot compel her children, aged 16 and 20, to read Tamil books or join the club.

“They can read Tamil but they are more into English literature,” she said. “You cannot force someone to read.”

To encourage reading in mother tongue languages (MTLs), the National Library Board (NLB) currently supports more than 40 active Chinese, Malay and Tamil language book clubs.

NLB co-curates book club programmes, provides spaces for these sessions and collaborates with book clubs during events such as World Book Day.

Ms Chow Wun Han, director of collection planning and development at NLB, said the clubs allow the public to share their literary interests with others and discover new works by overseas and local writers.

Beyond preserving language, reading clubs help build communities, develop critical thinking and encourage habitual reading, she added.

During a typical session, members meet to discuss a selected book they read beforehand. Membership in most clubs is free.

There is no official count of reading clubs here, as many are ground-up and independently run. English book clubs have had a pickup in interest recently. The Straits Times reported that at least seven or more have formed

An online exhibition on Chinese reading clubs in October 2025 said there are about 30 active groups here.

More youth wanted

Across Singapore, attracting young people to these clubs is an uphill task, as they often gravitate towards English books and reading clubs given the language’s prevalence.

Mr David Lee, vice-chairman of Xin Zhi Reading Club, one of Singapore’s oldest Chinese reading clubs, founded in 1997, said younger Singaporeans may not see the value of reading MTL books in their pursuit of academic or career advancement.

“It’s not simply about declining interest in Chinese,” the 60-year-old school counsellor said. “It’s the prevalence of English in our work and studies.”

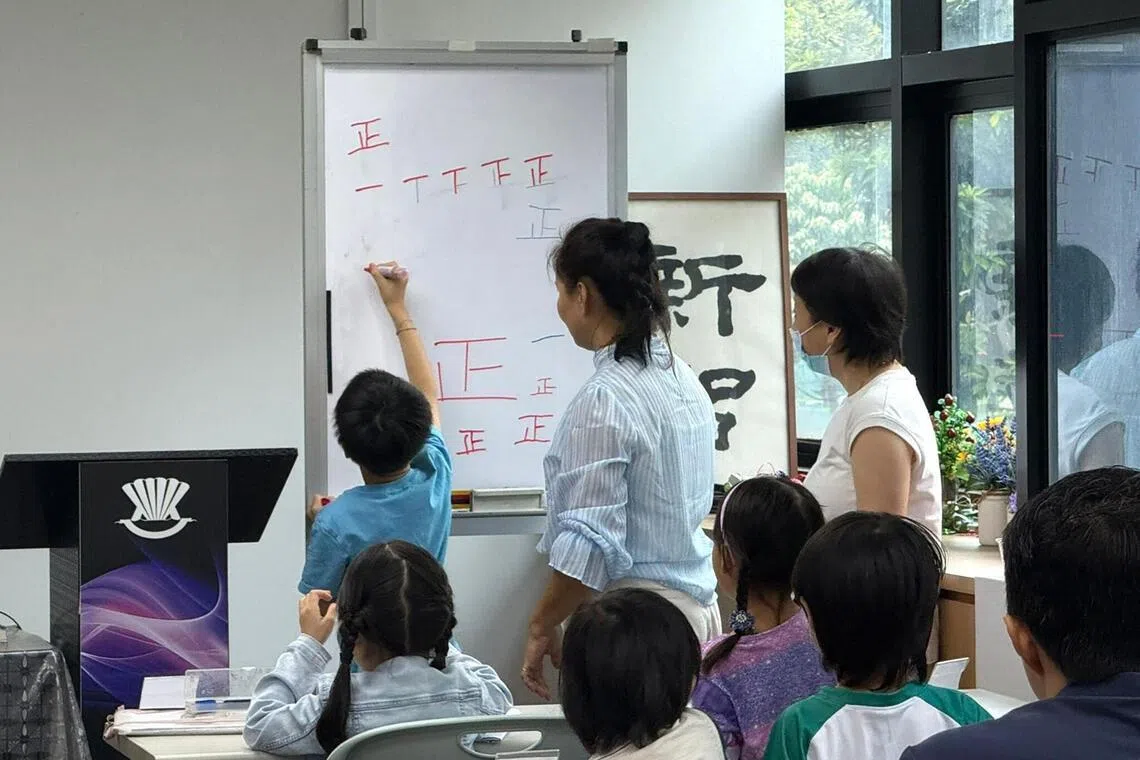

Xin Zhi Reading Club introduced parent-child lessons on classical Chinese texts to attract new members.

PHOTO: XIN ZHI READING CLUB

Xin Zhi has about 180 members, mostly aged 50 to 70.

Besides monthly reading sessions at Sims Avenue Centre, it organises calligraphy classes, ukulele workshops and community service projects, including reading with prison inmates.

It has also introduced parent-child classes on classical Chinese texts, and works with the Ministry of Education and NLB on reading competitions and World Book Day events to boost young people’s interest in their mother tongue.

A reading session organised by Xin Zhi Reading Club, one of the oldest active Chinese-language book clubs in Singapore, at Sims Ave Centre.

PHOTO: XIN ZHI READING CLUB

Mr Seng Say Lee, president of Taxi Shifu and Friends, said lifestyle changes have compounded the challenge.

The 86-year-old retired taxi driver said: “Besides English being our working language, younger people also tend to read from their phones, rather than physical books.”

The Chinese-language club, which meets six times a year at Ang Mo Kio Library, has about 40 regular members from their 30s to 80s. Its focus is on local Chinese titles.

Chinese-language book club Taxi Shifu and Friends, which meets six times a year at Ang Mo Kio Library, has about 40 regular members aged from 30s to 80s.

PHOTO: TAXI SHIFU AND FRIENDS

The club is open to walk-ins and non-members. Some sessions have attracted up to 100 attendees.

NLB has also set up MTL reading clubs to cater specifically to young readers.

It formed the Chinese-language Youth Readers Club for those aged 17 to 25, and the Starry Rain Book House for students aged 13 to 17 in 2024.

Ms Justina Sia, 22, a first-year business student at Nanyang Technological University and former secretary of the Youth Readers Club, said she made like-minded friends who wanted to explore culture and history. She left after two years because of her busy schedule, but noted that language confidence remains a key barrier. The club has about 15 members.

Ms Justina Sia, front row (right), said Youth Readers Club offers a space to meet like-minded friends to explore culture and history.

PHOTO: JUSTINA SIA

“When people hear ‘Chinese reading club’, their first reaction is, ‘My Chinese is not good’, so they avoid it,” she said.

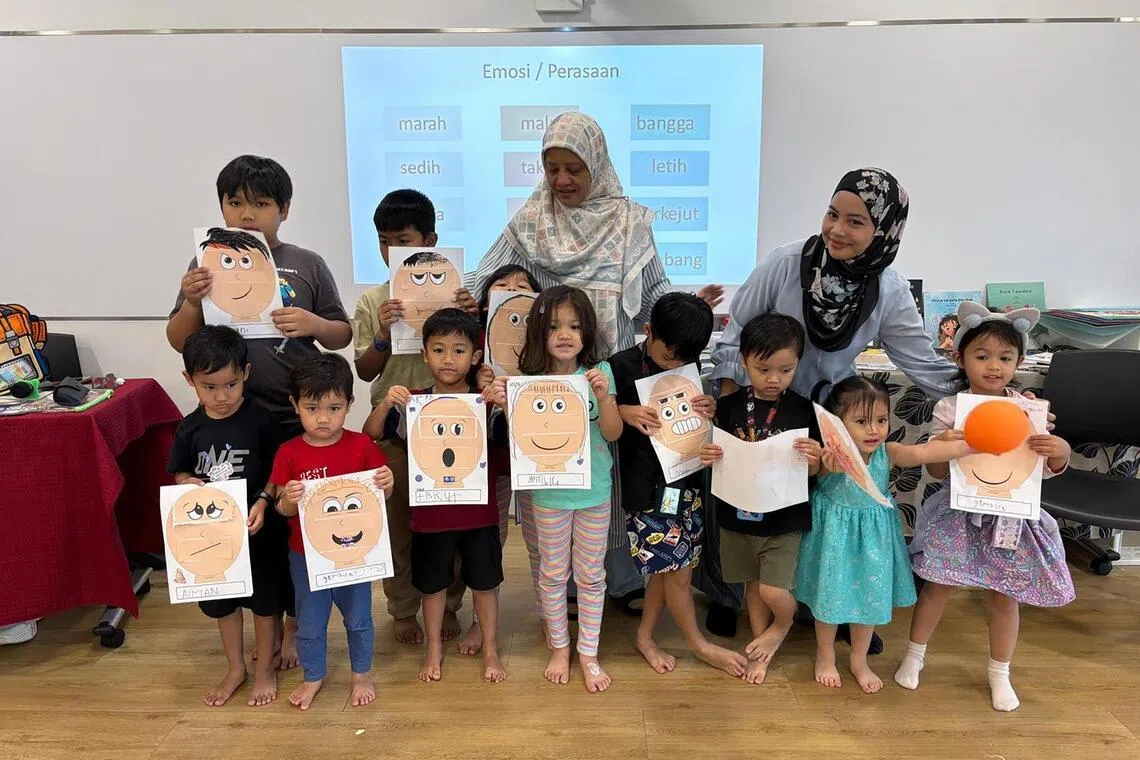

Parental encouragement from a young age is crucial, said Madam Norislinda Ismail, who has taken her six-year-old daughter Maya to Kelab Baca Ria sessions at Yishun Library for the past 1½ years.

The Malay-language reading club, established by NLB in 2024 for children aged four to eight, attracts 10 to 15 children with their parents monthly.

Established in 2024 by NLB, Kelab Baca Ria @ Yishun Library, a Malay-language book club for children, attracts 10 to 15 children with their parents monthly.

PHOTO: KELAB BACA RIA@ YISHUN LIBRARY

“My daughter is now interested in browsing Malay storybooks and speaks more Malay at home,” said the 41-year-old homemaker.

She added that the sessions are engaging as they incorporate acting, dancing, art and crafts, games and prizes.

Accessibility and relevance are key

Reading books is fundamental to both learning and appreciating a language, said Dr Lee Wee Heong, who oversees Chinese studies at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS).

“Books expose readers to the full expressive range of a language – its rhythm, imagery, cultural references, emotional depth and stylistic possibilities,” he said. “Through sustained reading, learners internalise vocabulary, syntax and discourse patterns in a way that rote learning cannot achieve.”

Award-winning local Tamil writer Azhagunila, 51, an active member of both Maya Literary Circle and another Tamil-language reading club Vaasagar Vattam, said an English reading club may give access to global literature, but a Tamil reading club strengthens cultural roots and gives a sense of pride in the rich heritage.

“Reading in our mother tongue helps us to inherit centuries of wisdom and carry forward traditions, values and voices that shaped our community.”

In Singapore, reading MTL books is especially important as everyday exposure to these languages outside the classroom is increasingly limited, Dr Lee said. The challenge, he added, lies less in cultural dilution than in changing reading habits and language use.

The 2020 Census of Population by the Department of Statistics Singapore showed an increase in English as the language most frequently spoken at home

Accessibility and relevance are key to drawing more to reading, said Dr Lee, who suggested social media book recommendations, short-form reviews and hybrid physical-digital events to target younger readers.

Singapore-based and regional MTL literature also reflects local experiences that resonate with the readers’ own lives, such as concerns about identity, social change and intergenerational relationships.

“In this sense, reading is crucial not just for language proficiency, but for helping learners see their mother tongue as meaningful, contemporary and connected to their identity,” he said.

Associate Professor Lim Beng Soon, head of the Malay language and literature programme at SUSS, suggested that MTL teachers can also be involved in the reading club activities to share their knowledge.

“These clubs can also help our young to understand the ethos, values and challenges of the community as reflected through local literary works.”