Singapore courts, unlike United States courts, are "leery" of going outside the text of the Singapore Constitution in declaring unspecified rights, as it is dissimilar to the US Constitution, which preserves rights not specified in text.

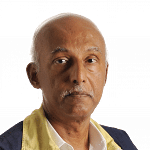

Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, in some of the clearest remarks on how the courts here deal with constitutional challenges, has underscored why courts have turned down suits filed to assert such rights and held that the matter was for Parliament.

"The more the judiciary is resorted to for the resolution of matters of searing social controversy, the more the line between legal and political questions will be blurred and the more likely citizens will begin to see the courts as a forum for the continuation of politics by other means," he told an audience in the US earlier this month.

Giving the annual Bernstein lecture in Comparative Law at Duke University's law school titled Executive Power: Rethinking the Modalities of Control, the Chief Justice discussed judicial review in Singapore, which he described as the "sharp edge that keeps government action within the limits of the law".

He said all legal power has legal limits, meaning that the constitutional role of the courts was simply to declare what the law is, and not what it ought to be.

This is unlike the US Constitution, where a "savings clause" preserves rights not specified in the document .

"By contrast, (the Singapore) Constitution does not have a savings clause that contemplates the possibility of unenumerated rights. It was for that reason that we have tended to be leery of going outside the confines of the text of the Constitution to find rights which petitioners have sought to assert," he said.

The Chief Justice cited a 2015 case in which a plaintiff asserted caning was a form of torture prohibited by the Constitution, even though there is no explicit prohibition against torture as such.

He said the Court of Appeal dismissed the case as the act complained about was not torture, but made clear that, even if it was, for the sake of argument, "where a right cannot be found in the Constitution (whether expressly or by necessary implication), the courts do not have the power to create such a right out of whole cloth simply because they consider it desirable".

Stressing the difference between the rule of law and the rule of judges, he said reading unenumerated rights into the Constitution would entail judges "enacting their personal views of what is just and desirable into law, which is not only undemocratic but also antithetical to the rule of law".

Chief Justice Menon said a restrained approach to the exercise of judicial power was mandated by the rule of law and the Constitution and pointed out that the courts are not well placed to address complicated policy issues and would remove these questions from the realm of democratic decision, with all its advantages, if they did so.

He said judicial review is most effective when the judiciary has secured the respect of the other branches through honest, competent and independent judgment that is respectful of the constitutional prerogatives of the other branches.

In such a climate, the executive will voluntarily review its policies and adjust its conduct in the light of the guidance given, even without the need for a formal challenge.

He noted that all countries have the difficult task of striking an appropriate balance between affording governments the ability to act swiftly and decisively in the public interest and providing for adequate safeguards against governmental excess.

There was no one correct model for all times and places, he argued.

"I can think of a number of cases where I wished that the law was other than what I concluded that it was and that a different result could be reached, but whenever I catch myself thinking in this way, I remind myself that it is neither my role nor do I have the constitutional mandate to say what the law ought to be, only to say what it is," said Chief Justice Menon.