News analysis

2024 is first Dragon Year since 1964 that failed to lift Singapore’s fertility rate

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

![CMG20240228-JasonLee01/出生率下降:拍婴儿 [Blk 103A Bidadari Park Drive]Generic photos of 5 months old baby.](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/straitstimes/0c1db98a4f996c6b0502ebfbb9451d5cae4eacab5f0d454770c42fef8d945796)

In 2024, Singapore’s resident total fertility rate held steady at 0.97 - a historic low first reached in 2023.

PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO

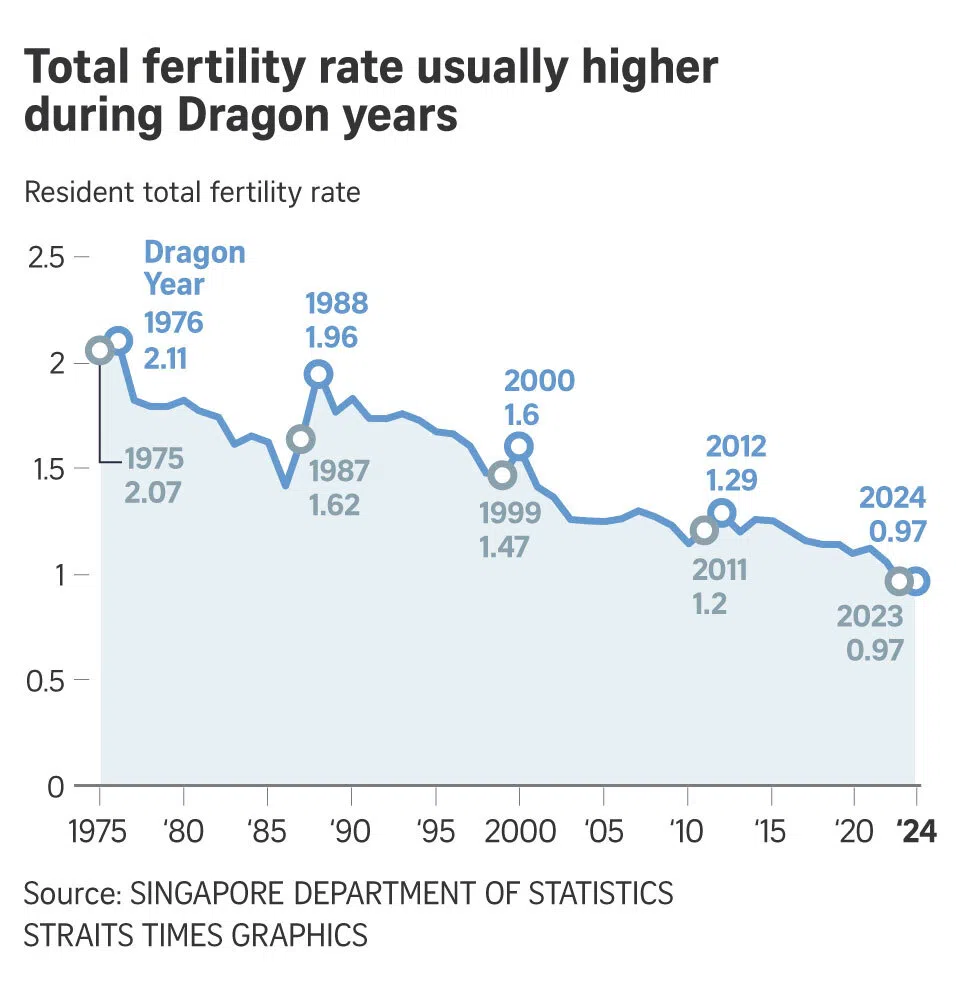

- 2024 marked the first dragon year since the 1964 dragon year when the overall total fertility rate (TFR) was not higher than the preceding year.

- Sociologists cite financial security, career concerns, and weaker beliefs in auspicious years as reasons for low fertility rates, despite government incentives.

- A 1.2% rise in citizen births in 2024 was offset by an increased childbearing-age female population, indicating no change in fertility behaviour, posing long-term challenges.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – So the 2024 Dragon Year failed to deliver the baby boom that was much hoped for.

But more than that, 2024 also marked the first Dragon Year since the 1964 Dragon Year when the overall total fertility rate (TFR) did not rise from the year before, based on public data records since 1960.

Instead, in 2024, Singapore’s resident TFR held steady at 0.97 – a historic low first reached in 2023. It was also the first time the TFR, which refers to the average number of babies each woman would have during her reproductive years, fell below 1.

The latest TFR figures were contained in the Population In Brief 2025 report released by the National Population and Talent Division on Sept 29.

Traditionally, the Dragon Year – which comes around every 12 years in the Chinese zodiac calendar – is considered auspicious for births.

Parents once planned to have “Dragon babies”, who are believed to be destined for good fortune, success and leadership, among other desirable traits.

In past cycles, this translated into significant increases: The TFR rose from 1.47 in 1999 to 1.6 in 2000, and from 1.62 in 1987 to 1.96 in 1988.

The years 1988 and 2000 were Dragon Years.

The only other exception was the 1964 Dragon Year, when the TFR fell from the year before.

But that came amid a broader fertility decline in the 1960s as Singapore’s economy developed and family planning policies started to take hold, said the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) senior research fellow Tan Poh Lin.

Sociologists and academics say that financial security, career development and childcare concerns far outweigh zodiac considerations when it comes to having children these days.

Dr Mathew Mathews, head of the IPS Social Lab, said that attitudes and conditions were different in the earlier decades, which saw a bump in births during the Dragon years.

In those years, Singaporeans had fewer fears about career trade-offs, and felt they could better afford the cost of housing and raising a child, he said.

At that time, couples also wed at a younger age, so they could have more children if they wanted, or at least face fewer fertility issues, as fertility declines with age, he said.

Now, Singaporeans are more worried about career or lifestyle trade-offs if they have children. The lingering economic uncertainty and concerns about the cost of living are also stronger than any zodiac effect, Dr Mathews said.

Rising education levels also mean that beliefs about auspicious years have weakened, he added.

Small uptick in TFR for Chinese women

Dr Tan pointed out that there was a “small uptick” in the TFR for Chinese women in 2024, although the overall TFR, which is calculated based on women of all races, remained unchanged from 2023.

The TFR for Chinese women was 0.83 in 2024, up from 0.81 in 2023.

Meanwhile, the TFR for both Malay and Indian women fell from 2023 to 2024.

Dr Tan said it is “too hasty” to conclude the Dragon Year phenomenon no longer exists, although its effect has waned over time.

The Population In Brief report showed that citizen births – babies with at least one Singaporean parent – rose by 1.2 per cent, from 28,877 in 2023 to 29,237 in 2024.

IPS senior research fellow Kalpana Vignehsa noted that besides the number of births, the calculation of the TFR also takes into account the size of the female population of child-bearing age.

If the number of such women rises in step with births, the TFR may stay flat or even fall.

Dr Vignehsa called the 1.2 per cent rise in citizen births a “marginal bump”, and not a structural shift.

The unchanged TFR, she said, shows that the larger number of births was offset by a larger pool of women of childbearing age.

“In other words, fertility behaviour didn’t change. What changed was just population size dynamics. So in the scheme of things, it’s not significant.”

Existential problem, lasting implications

Singapore’s ultra-low fertility rate – among the world’s lowest – coupled with its rapidly ageing population, poses an existential challenge.

In 2026, Singapore is expected to become a super-aged society, defined by the UN as one where at least 21 per cent of the population are aged 65 or older.

In 2025, 20.7 per cent of Singaporeans are already in this age group, up from 13.1 per cent in 2015.

Dr Mathews said that as families shrink and seniors age, there are fewer people to look after loved ones who need care.

He said: “Ultimately this means that more will need to rely on state and community resources, and even employers’ support to manage the care demands, (which are) now provided by very few individuals.”

Dr Vignehsa said that with a TFR below 1, over time, this means fewer Singaporeans entering the workforce, heavier reliance on foreign labour and greater productivity pressures to sustain economic growth, among other challenges.

She added: “Singapore already leans on immigration to mitigate the demographic crunch, but relying too heavily on immigration without a sustainable citizen birth rate raises long-term challenges relating to social cohesion and identity.”

The Government has introduced a slew of policies and initiatives to encourage the stork, ranging from more parental leave, higher childcare subsidies and promoting flexible work arrangements.

The Large Families Scheme was recently introduced to provide additional financial support of up to $16,000 for each third and subsequent citizen child.

Whether such policies will lift the TFR remains to be seen – but at the very least, the hope is that it will not fall further.