Coronavirus pandemic

Being quarantined taught me not to be complacent

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

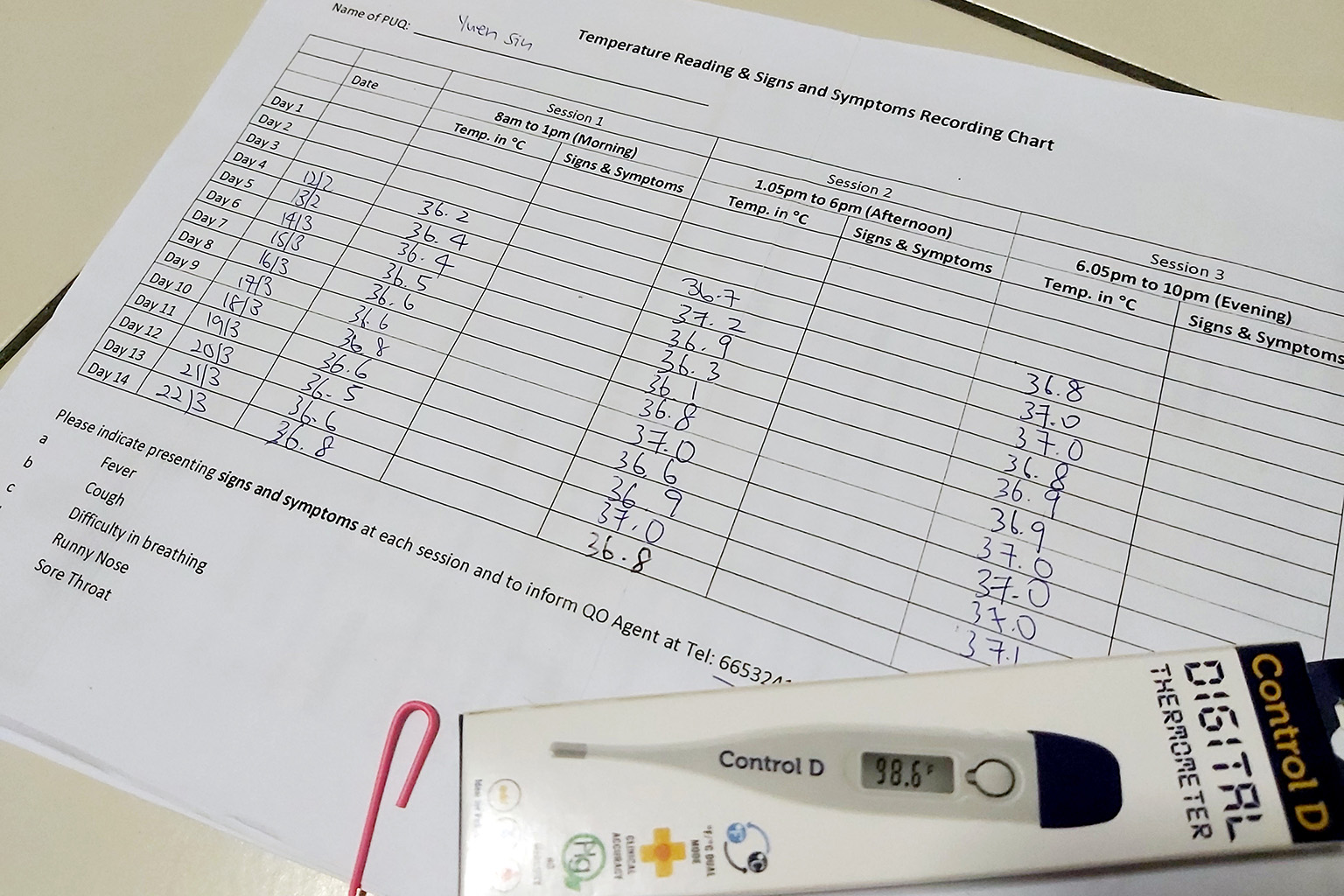

The writer’s temperature log, which she had to fill in three times a day, on top of monitoring herself for symptoms such as fever, sore throat and breathing difficulty, while she was quarantined at home.

ST PHOTO: YUEN SIN

At the beginning of the month, the coronavirus situation in Singapore had appeared to be improving.

The number of cases reported daily was tapering off, with just a few new ones every day.

While there were reports of the outbreak escalating in countries such as South Korea and Italy, things in Singapore were generally calm, though additional measures such as temperature screening had to be observed.

Events and meetings carried on, and people continued going to shops and restaurants, though some were emptier than usual.

Even Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong was encouraging Singaporeans to give the tourism sector a much-needed boost by visiting local attractions or booking staycations.

As long as we took precautions such as washing our hands frequently, life could go on as normal, I thought - until I was issued with a home quarantine order on March 11.

Here's what happened: I had visited a climbing gym a few days before, and I happened to be there at the same time as someone who was later diagnosed with Covid-19.

The contact tracer from the Ministry of Health (MOH) who had called me could not tell me if I had been in close proximity with the patient during the few hours that I had spent there, but it appeared that everyone who had been at the gym that day at the same time as the case had to be quarantined.

It was likely that MOH was being more careful, as the contact tracer told me that many could have touched the same surfaces on the climbing walls even if they were not in close contact with the confirmed case.

In the absence of more information that could help me determine whether I was really at risk of being infected - how close was I to the case; were we at the same areas in the gym; and did we touch the same surfaces? - fear and worry began to set in.

Most of all, I felt guilty towards the people I had been in contact with, though they assured me that I was not to blame. Before I found out about the quarantine order, I had met a group of friends, had meetings with two work contacts and also covered a business forum for work. I had not felt ill at all.

Though there was no official obligation to do so, I informed these contacts about my quarantine order, and told them to monitor their health closely over the next two weeks. I was also worried about my parents, who are in their 60s, and began isolating myself even before the quarantine papers were issued to me.

We often go about our daily lives without paying much attention to little habits that we have, such as touching our faces. But in those moments of receiving the news about being potentially at risk, I started to play back my interactions with others like a movie in my head, alternately reacting with relief and regret at my actions.

Strike one - my friends and I had ordered food in for dinner when we met at a friend's house, and decided that we could go without serving spoons for dessert because it was troublesome to do so.

Strike two - while meeting someone for a contact lunch, we had also shaken hands despite general advisories cautioning against this.

On the plus side, I had remembered to wash my hands thoroughly after leaving the climbing gym, and had not touched my face at all while I was inside. While covering a business forum the next day, I had also kept far away from the VIPs, which meant they were not at risk at all.

Because I was working from home, I had not come into contact with most of my colleagues, which spared them potential inconvenience if the worst-case scenario of me coming down with Covid-19 happened.

As the days of my quarantine passed, things began to look up. My temperature readings, which had to be taken thrice a day and reported to an MOH officer via video call, were normal.

I did not experience any symptoms, and I also found out from a circular that the patient who had been at the gym had been in a different area from me, which meant that I was probably at low risk.

Still, I took extra precautions, and avoided meeting people on March 22 after my quarantine order lifted at noon.

My experience also gave me an appreciation of the intense work that goes on behind the scenes in Singapore's efforts to contain the coronavirus. The MOH contact-tracing team had called me promptly, despite the fact that more than 100 people also had to be quarantined on the same day that I received notice.

The Certis officers also had to work late into the night to deliver the quarantine papers and call people to inform them of what they had to do, on top of manning a 24-hour hotline that quarantined people can call if they have any queries or face any issues.

With more than 38,000 people now serving out stay-home notices, the workload of those in charge of enforcing such notices has also probably increased exponentially. It is not easy work.

The coronavirus situation has escalated over the past few weeks, with the World Health Organisation labelling it a pandemic and numerous countries going into lockdowns.

Life in Singapore cannot go back to normal, at least for the next few weeks - all workers are now being urged to telecommute if possible, and you risk jail or a fine if you venture out of your house on a five-day MC, or if you intentionally fail to observe safe-distancing guidelines.

After my quarantine scare, my family also started using serving spoons during meals and separate toilets as a precautionary measure.

I'm minimising activities that will put me in close contact with strangers, such as going to yoga studios or gym classes.

Some may think the measures are too stringent and question their necessity. Others may cite instances where it may not yet be practical or feasible to carry out such measures - such as on public transport during peak hour - and conclude that there is no point in rolling out safe distancing if it cannot be observed across the board.

In our daily lives, it is also not so easy to shift norms or behaviour.

Shaking hands feels like the intuitive, polite thing to do. It feels awkward to insist on keeping your colleagues at arm's length if you see them in the office. Telecommuting for work is troublesome, and it feels depressing to have to cut down all physical social interactions to a minimum.

But every little step counts.

Whether or not you observe these steps could have a direct impact on whether you may be classified as a close contact, or on the likelihood of you developing symptoms should someone in your midst come down with Covid-19.

And with the number of cases now spiking in Singapore, owing to a rise in imported cases, the chances of one coming into contact with someone infected are much higher.

Completing my quarantine does not grant me any immunity to Covid-19, and though nobody is to blame if they come down with the disease, we can all play a part in containing this situation so that one day, we can finally start having gatherings, events and overseas holidays to look forward to.