Are school-issued iPads and Chromebooks becoming a distraction in S’pore classrooms?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

All secondary school students have received personal learning devices since 2021.

PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO

SINGAPORE – Eighteen seconds spent on Google Classroom and more than three hours on entertainment apps like YouTube and TikTok. This was what parents discovered about how their 13-year-old son had been using the school-issued iPad during school hours.

The Secondary 1 student, from Gan Eng Seng School, admitted to his parents that more often than not, he had not been paying attention during lessons as he had been playing online games on his iPad under the table in the classroom.

All secondary school students have received such school-sanctioned tablets or personal laptops since 2021, after the Ministry of Education (MOE) brought forward its original 2028 target by seven years. Online learning became more prevalent during the Covid-19 pandemic, and schools have begun to introduce regular home-based learning.

Schools select from a range of device types – mostly iPads or Chromebooks – and the intent is for all students in the school to be using the same device, for lessons and assignments on online platform Singapore Student Learning Space (SLS), both at home and in classrooms.

But not everyone is in favour of having access to screens in school.

At least eight parents told The Sunday Times that they feel the personal learning devices (PLDs) have caused more distraction in the classroom instead of enhancing learning, and several teachers said they often catch students checking messages or playing games.

Some parents from Gan Eng Seng School said their children have been constantly distracted by their PLDs during lessons since receiving them in April.

The parents said their children would typically spend three to four hours on non-educational activities on their iPads each day in school, based on screen time checks.

These include browsing Instagram and TikTok, using messaging apps like WhatsApp, and taking photos of their teachers and classmates. Some students would plug in their ear buds, move to the back of the classroom and listen to music on Spotify or watch videos on YouTube.

One parent said her child was able to play an online soccer game for five hours while in school.

Most of the parents spoke on condition of anonymity and did not want to reveal personal details for fear that their children would be singled out in school.

Getting past restrictions

All PLDs are pre-installed with a device management application, like Mobile Guardian or Blocksi, that blocks students’ access to undesirable internet content, such as pornography and gambling, and sets screen time limits.

After a global cyber-security breach affected 13,000 students from 26 secondary schools

The worry is that teens will be able to download formerly restricted apps before a new application to manage the use of students’ devices is rolled out. This is slated to be in place by January 2025.

But parents said students had previously been able to bypass the pre-installed device management apps.

A secondary school teacher said students in her form class in 2021 – among the first batch to receive PLDs – already knew how to get around restrictions.

“Within a few days, I saw that they had figured out how to use various chat, entertainment and gaming apps on their devices. Many would then choose to stay back in class to use their Chromebooks during recess and lunchtime, instead of going down to the canteen to eat and socialise.”

Mr Andrew Soo, 50, a nurse, said he and his wife set limits on the use of their two sons’ PLDs at home, but they have no control over usage when they are in school. He declined to reveal the names of their schools.

YouTube and game websites are accessible on their PLDs, he said, even with Mobile Guardian installed. He prefers to install his own parenting software but cannot because of Mobile Guardian.

Both boys, 15 and 17, have their own mobile phones, but Mr Soo uses Google Family Link to restrict their usage, so they can use their phones only for WhatsApp and listening to music.

His younger son was eventually referred to a school counsellor to help manage his iPad usage, and has managed to reduce his screen time since.

Added burden

Parents say they now have to manage the use of another device at home, other than their teenagers’ smartphones. Also, they are often told by their children that the PLDs are needed for school assignments, when this may not always be true.

“I feel like 007. I constantly have to outwit my child so that he doesn’t misuse his PLD,” said the mother of a Gan Eng Seng School student, who is always one step ahead of her in devising ways to covertly use his school-issued iPad at home.

For example, when told to keep his iPad on the table where she could see it, the son placed an empty iPad cover as a decoy instead. She realised he would then head to the bathroom to play games on the device.

She has since confiscated her son’s PLD and is considering not letting him use it in school next year. She said she informed the school leaders and they did not object.

Another parent said her son was able to reset parental controls on his school-issued iPad by creating another user account on the device and using that to log in.

“The kids find out how to reset the factory settings, and then we have to start all over again. I feel like trust has been lost, and it has impacted relationships in the family,” she said.

Parents say the guide given to them on activating parental controls is not enough to thoroughly understand how to manage the PLDs effectively. There are also so many permutations and possibilities when it comes to setting controls.

In response to queries, Gan Eng Seng School said the use of PLDs in the classroom has educational value. With the devices, the school has observed “stronger student ownership” in learning as students are engaged to provide responses on online platforms.

“Students are also taught when, where and how to seek help when needed, for example, when there is misuse of the PLD or when one struggles with excessive use of digital technology,” the school said, adding that it will continue to work with parents to monitor their children’s PLD use closely at home.

The school will also provide counselling, referrals and further intervention when needed, for those who need additional support.

Do screens add value to learning?

When Mr Alex Tan, 45, a sales director, checked his 14-year-old son’s iPad usage on a school day in September, he found that his son had spent three hours and 29 minutes on games and 30 minutes on educational activities.

Calling the device a double-edged sword, Mr Tan said his son could not download many creative apps, such as Procreate, because of Mobile Guardian.

“I want to encourage him to draw and create mind maps to recap what he has learnt, but he couldn’t do it previously. Now without Mobile Guardian, he can, and it is good for his learning.”

Several parents said the PLDs are mainly used for purposes like accessing soft-copy notes on Google Classroom and attempting online assignments on SLS.

If homework required the use of a mouse or keyboard, the students would end up using their parents’ laptops to get it done.

In classrooms, different teachers have varying approaches when it comes to adopting technology for learning. A humanities teacher, who has been in the service for more than 25 years, said learning how to use PLDs during lessons was a steep learning curve.

“When I started teaching, we were using transparencies. Now we have Google Classroom, so I have had to evolve,” said the teacher, who uploads notes to Google Classroom for her students to retrieve.

The teacher, who is in her late 50s, also uses the PLDs for her students to do project work on platforms like Canva.

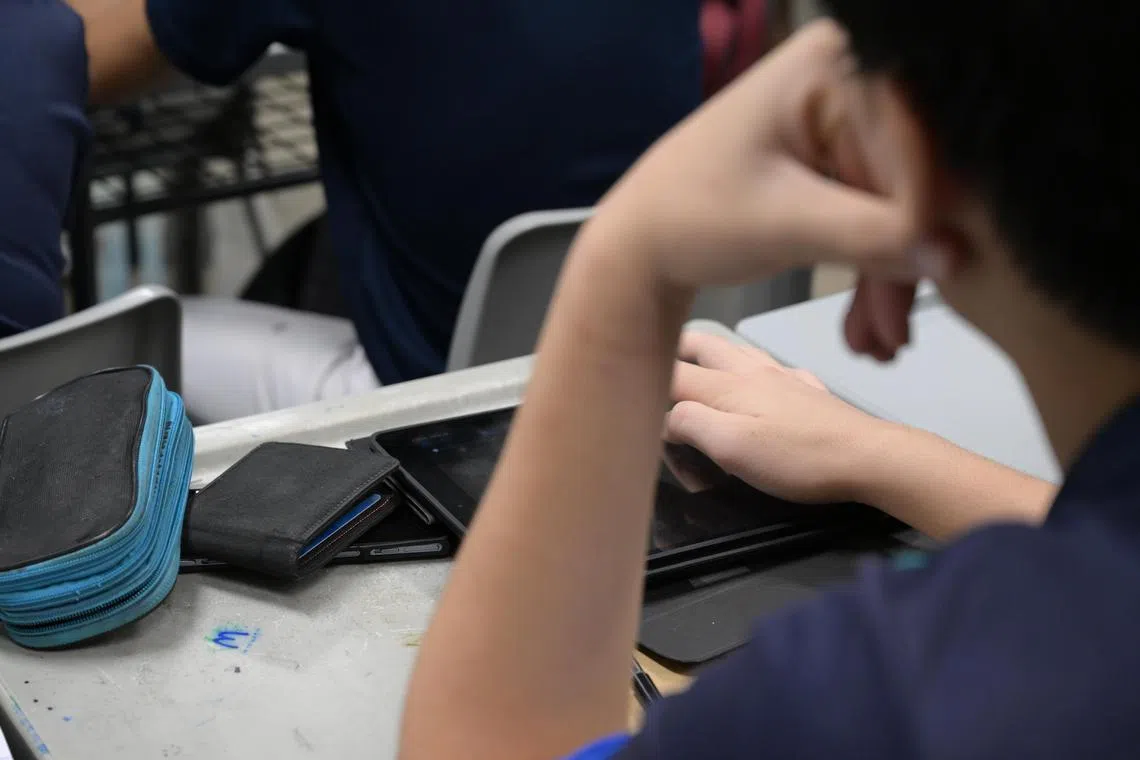

Some parents said their children would typically spend three to four hours on non-educational activities each day in school on their iPads.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

An English-language teacher, 33, who has been teaching for eight years, said that with PLDs, his students are able to work together and share knowledge on platforms like Padlet and Google Sheets.

This interactive approach to learning in real time makes lessons more engaging, he said.

“During class discussions, I may not be quick enough to capture every single person’s point of view if I rely on myself and the whiteboard. It all gets lost in the air. These platforms allow us to capture all our thoughts, and they become a repository for students to refer to.”

That being said, teachers noted that sometimes, it is easier not to use PLDs during lessons to avoid technical difficulties, such as connectivity issues or low battery levels, and minimise the chances of students being distracted.

A science teacher, 38, said she has caught students on several occasions using the devices to check messages and play games. She would give them verbal warnings first before confiscating their PLDs for the rest of her lesson.

What is the right age to introduce screens in schools?

Some like Ms Carol Loi, a digital wellness educator, feel that it would be more appropriate to introduce screens for learning in school later, like in Secondary 3.

“At Sec 1, they are trying to make new friends, get used to more subjects, and they feel a lot more pressure. So maybe we should give our young people a chance to settle (in) first,” said Ms Loi, 53.

“If we want to give PLDs at Sec 1, then we need to prepare them from primary school. That means in upper primary, we should be teaching kids how to use social media and how to manage their time on their devices.”

Apart from providing parents with guides, schools and parents need to have deeper conversations about supporting children in the use of digital devices at home and in school, she added.

Responding to queries, an MOE spokeswoman said the PLD initiative aims to provide opportunities for secondary school students to develop digital literacy and technological skills, as well as good digital habits for an increasingly tech-saturated environment.

To ensure that the PLD is used safely and responsibly during school hours, schools have standard operating procedures and classroom routines to guide student behaviour, as well as teacher-led instructions, she said.

Self-regulation increases with maturity and adult teaching and reinforcement, she added.

Parents play a key role in guiding and monitoring their child’s leisure online activities, she said, and they can provide feedback to the school on their child’s inappropriate use of PLDs. For students who require more support, schools will put in place measures to help them regulate their use of PLDs.

“It is important for schools to embrace educational technology to enrich our students’ learning experiences. This will allow our students to grow up to be digitally savvy and take on the opportunities and challenges of the future,” she said.