An Australian ‘lightbulb’ that illuminates science secrets

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

ST breaks down the nuts and bolts of the Australian Synchrotron and the range of scientific discoveries it can open doors to.

PHOTO: AUSTRALIA'S NUCLEAR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ORGANISATION (ANSTO)

SINGAPORE - From 2023, more Singapore scientists will get to use a high-tech research facility in Australia

The Straits Times breaks down the nuts and bolts of the Australian Synchrotron and the range of scientific discoveries it can open doors to, and how it compares to the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source.

Location of the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source at the National University of Singapore and the Australian Synchrotron in Clayton, Melbourne.

ST GRAPHIC: LIM YONG PHOTO: KRZYSZTOF BANAS

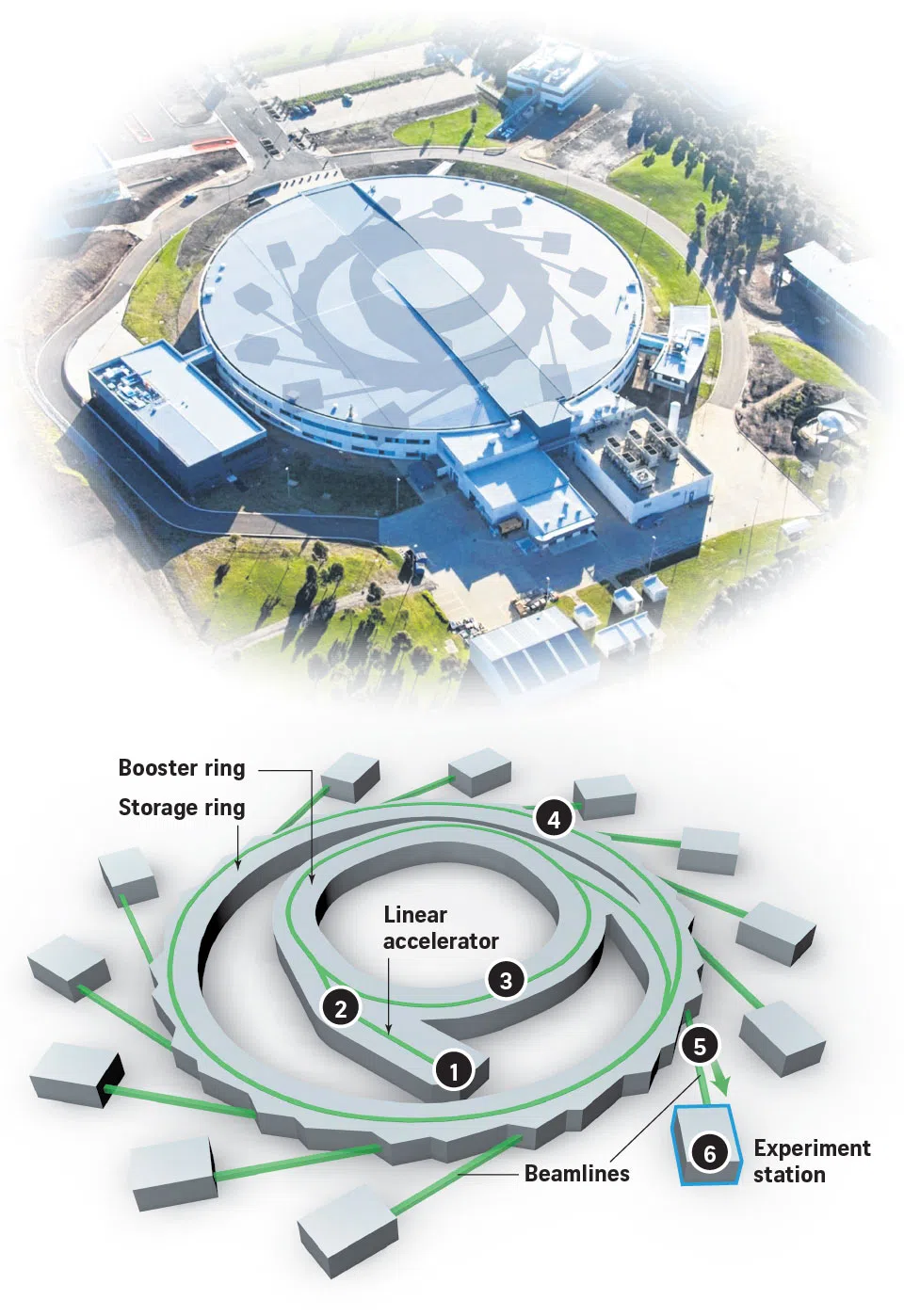

The Australian Synchrotron

Illustration of the synchrotron’s interior.

ST GRAPHIC: LIM YONG

What is it

The stadium-like building in Clayton, Melbourne, houses a network of tunnels inside that are connected to numerous experiment stations.

Energised electrons whizz through the tunnels to create intense light across the electromagnetic spectrum that reveals the innermost secrets of objects – from a fossil to human tissue.

What it does

An electron gun shoots out electrons, which travel down the linear accelerator.

Microwave radiation is also pushed into the accelerator, to enable the electrons to reach 99.9997% of the speed of light.

Pockets of electrons are injected into the booster ring, and their energy is raised from 100 million volts to 3 billion volts. The electrons reach 99.9999985% of the speed of light.

The heavily-charged electrons are pushed into the outer storage ring. When magnets in the ring cause electrons to bend, the electrons release energy in the form of light – which can be up more than a million times brighter than the sun.

The light energy – which ranges from infrared to visible light to x-rays – will be filtered to travel through separate beamlines into individual experiment stations.

Scientists carry out experiments here. To study proteins and viruses, for instance, a station with an x-ray beam would be suitable.

Top: An illustration of an experiment chamber. Below: The synchrotron’s X-ray-fluorescence microscopy experiment chamber.

ST GRAPHIC: LIM YONG PHOTO: THE AUSTRALIAN SYNCHROTRON

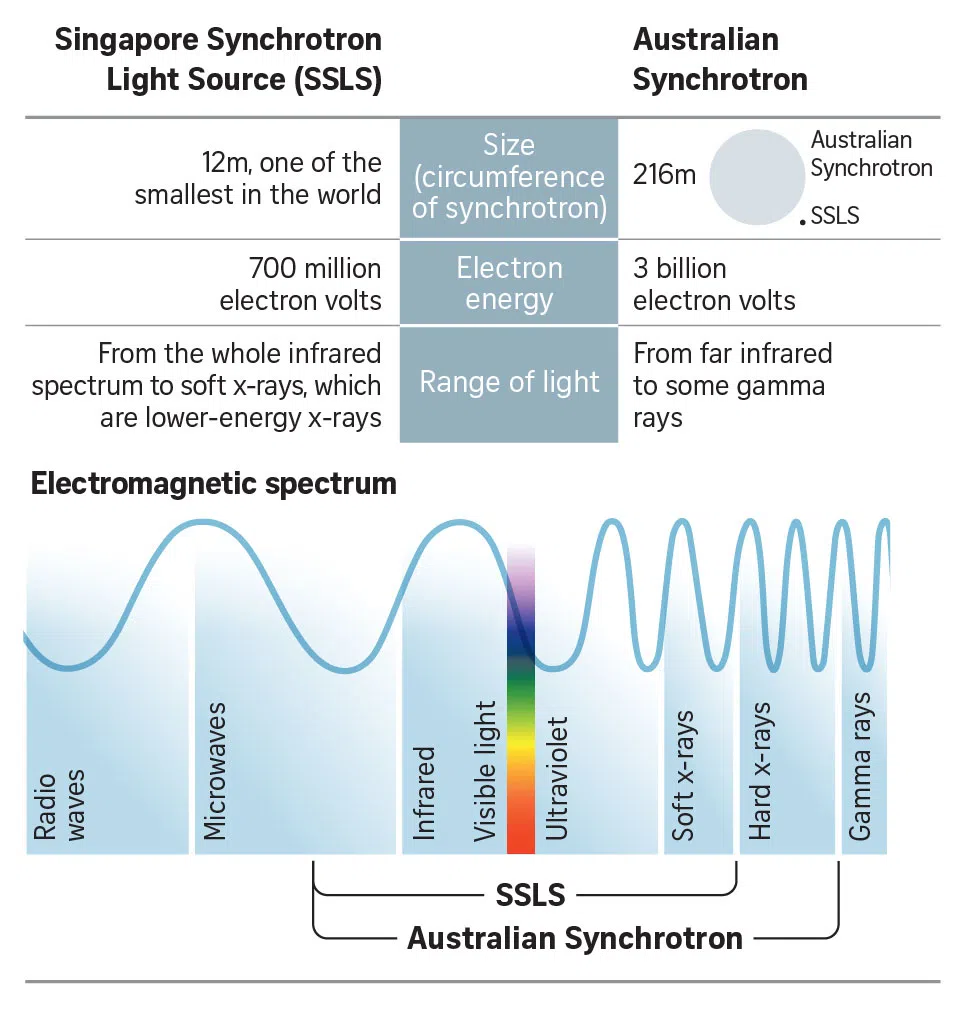

Singapore V Australia

How SSLS and the Australian Synchrotron differ.

ST GRAPHIC: LIM YONG

Singapore and the Australian Synchrotron

In October, Singapore inked an agreement to allow Singapore researchers preferential access to the Australian Synchrotron. Australia’s facility is more advanced than the compact Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS) at the National University of Singapore.

While Singapore’s facility is suitable for the physical sciences, it is not primarily equipped to support biomedical research, said senior research fellow Chen Ce-Belle from the NUS Physics department.

This is because the SSLS does not have hard, or high energy, x-ray beams that can penetrate thicker samples such as living tissue.

The range of light SSLS produces ends at the soft, or lower energy, x-ray region. Without hard x-rays, scientists here have to place their biological samples in a vacuum environment or dehydrate them, which kills living samples, limiting what they can study.

Dr Chen is looking to access Australia’s facility to study human development and cancer therapies. Singapore scientists have submitted more than 30 research proposals to access the facility Down Under.

How high-tech Synchrotrons boost science

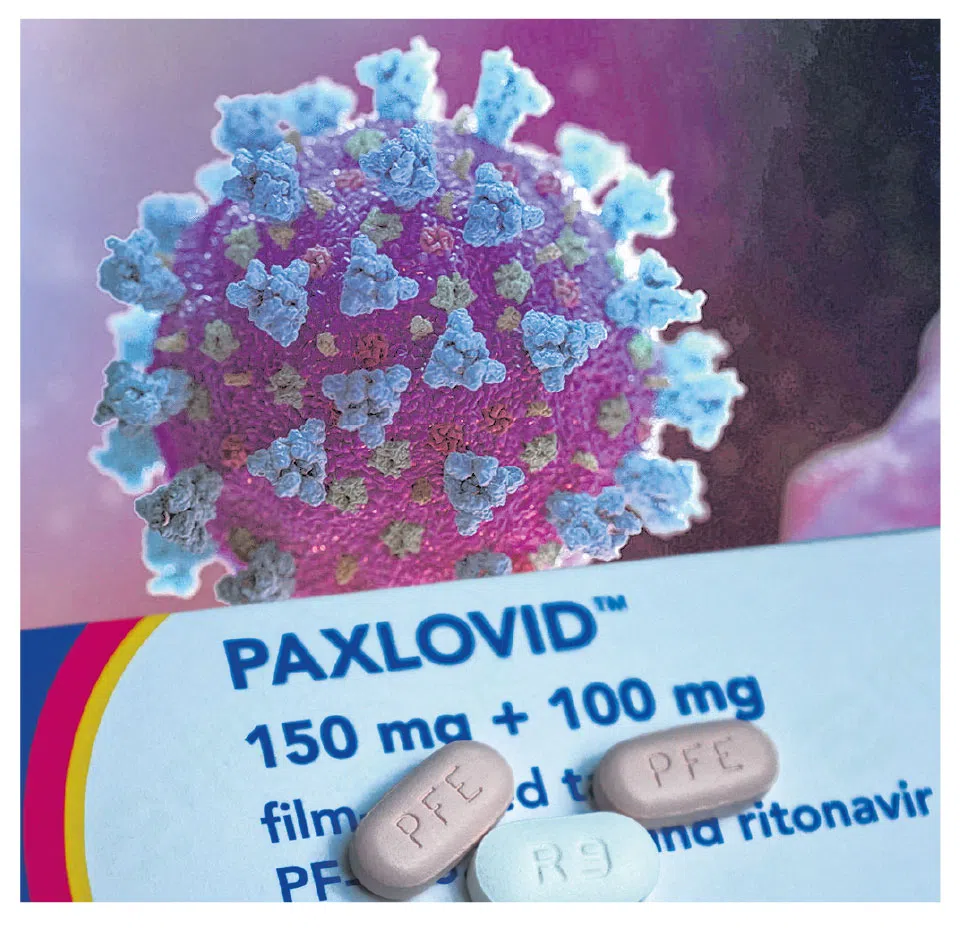

Developing Covid-19 drugs

Paxlovid was developed with the help of a synchrotron.

PHOTOS: REUTERS

When a hard X-ray beam is aimed at molecules, such as copies of the Sars-CoV-2 spike protein, the protein’s structure is amplified.

When scientists inject a potential antiviral into a solution containing the spike protein, they can observe if the drug is effective in stopping the virus from replicating.

Pfizer’s antiviral drug Paxlovid was developed with the help of a synchrotron.

Deep dive into volcanic eruptions

This satellite image shows smoke and ash being released by the Hunga-Tonga - Hunga-Haa’pai volcano just over one week before a massive eruption destroyed most of the island on January 15.

PHOTO: AFP, MAXAR TECHNOLOGIES

Like a human CT (computerised tomography) scan, X-ray beams can penetrate volcanic rock to reveal its components and hidden gas molecules.

Scrutinising volcanic rocks allows scientists to look back in time and map out how a volcano erupted the way it did.

The undersea Hunga TongaHunga Ha’apai volcano erupted in January, becoming the largest eruption of the 21st century so far. A volcanologist from New Zealand collected volcanic samples and fragments to nd out how the unexpected eruption happened, with the Australian Synchrotron’s help.

He hopes the micro clues gained from the research on Hunga could then be applied to better monitor volcanoes in the Pacific. Hunga is located in the South Pacific Ocean.

Hidden painting

Portrait of a woman by French painter Edgar Degas.

PHOTO: NATIONAL GALLERY OF VICTORIA

Art experts at Australia’s National Gallery of Victoria had a hunch that French artist Edgar Degas’ Portrait Of A Woman was painted over another artwork. Hints of the concealed painting appear as dark smudges on the woman’s left cheek.

To uncover the mystery, powerful X-ray beams were red across the canvas at the Australian Synchrotron.

The researchers detected different metallic elements in the pigments that Degas used, which included copper, zinc and cobalt.

They digitally reconstructed the hidden painting – a fair woman with auburn hair.

A digital reconstruction of the hidden painting.

PHOTO: SCIENTIFIC REPORTS

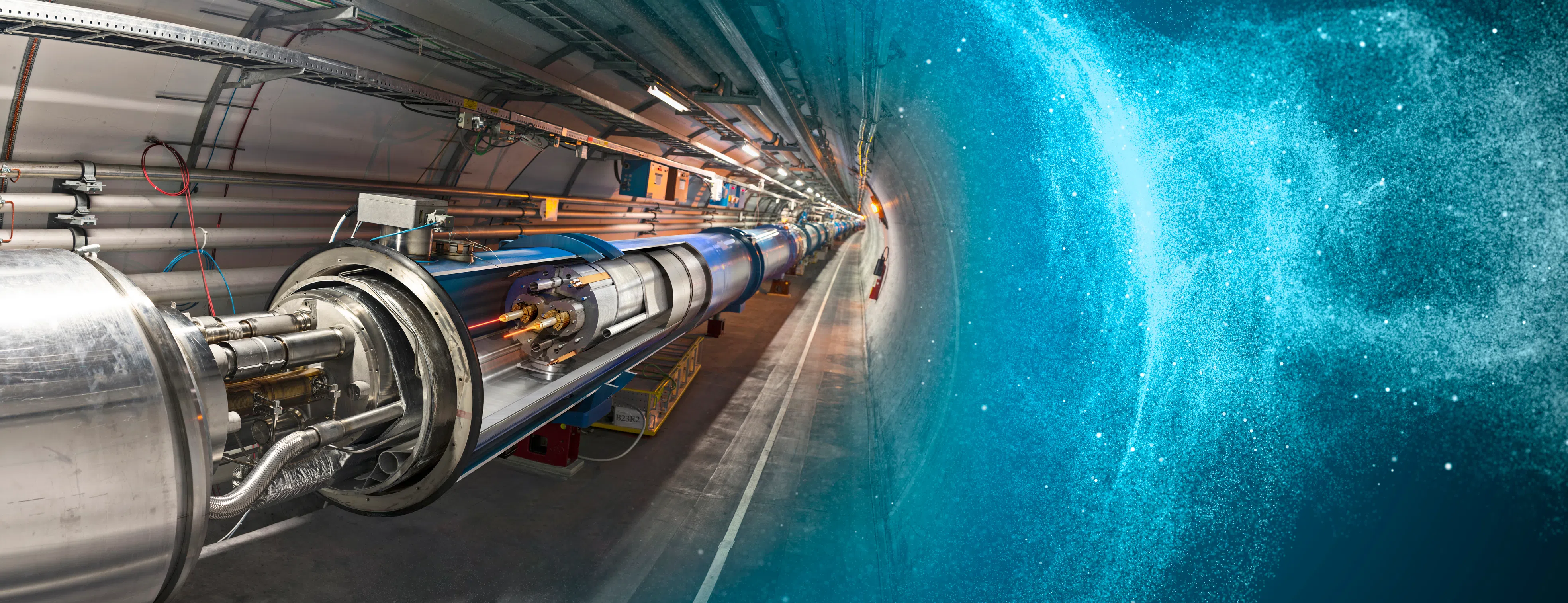

Synchrotron v Large Hadron Collider

The Large Hadron Collider

PHOTO: CERN

The Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, Switzerland, is the world’s largest science experiment.

While both mega-structures accelerate charged particles, their objectives are different.

The Large Hadron Collider makes subatomic particles such as protons smash together millions of times per second, to study the fundamental forces of the universe.

SOURCES: PROFESSOR MICHAEL JAMES, PROFESSOR MARK BREESE, ANSTO, NATIONAL RESEARCH FOUNDATION