Allow youth above 14 to seek help without parental consent: Mental health treatment providers

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

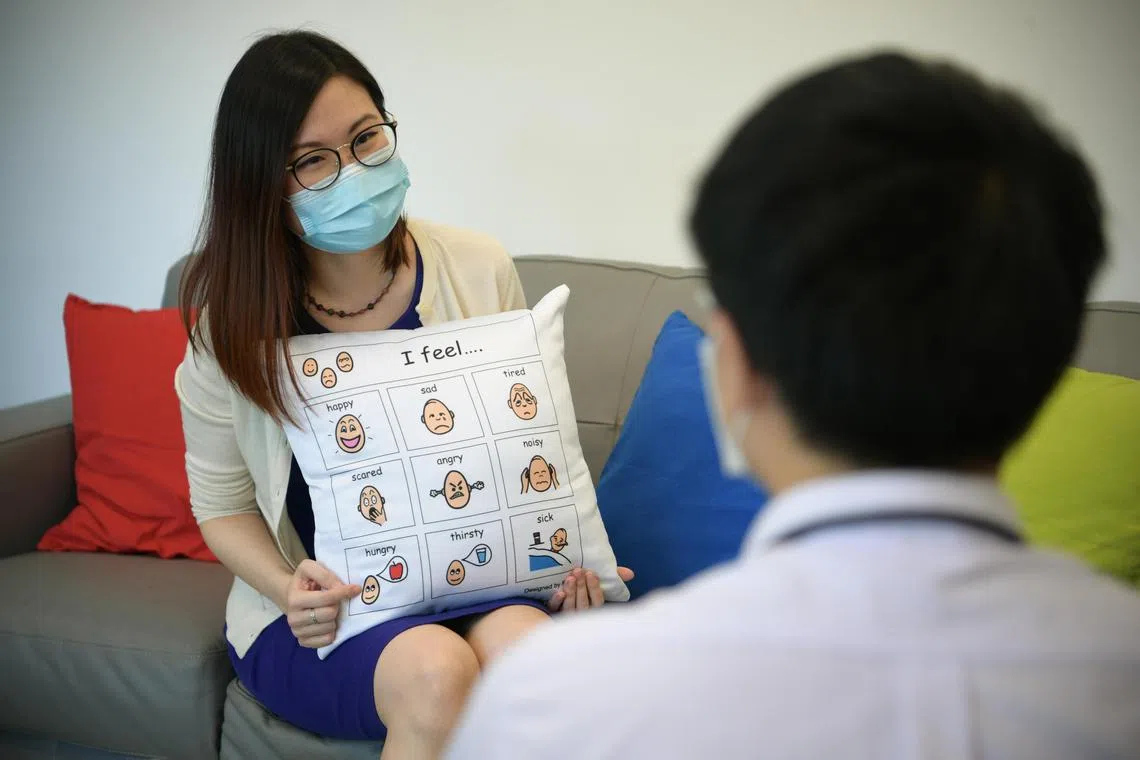

With the need for parental consent, some young people do not seek help for their mental health.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE - A teen with anxiety issues turned to an external counsellor for help, as he did not wish to see the one provided by his school. When told that his parents would have to consent to his treatment, he flatly refused.

“He said, ‘Never mind, I will just wait till my 18th birthday’,” a counsellor told The Sunday Times.

With the need for parental consent being a key reason why some young people do not seek help for their mental health, some mental health treatment providers here are calling for the removal of such a requirement for those above the age of 14 – an age when many begin to show symptoms.

At the same time, safeguards should be put in place for situations where the young person’s safety or those around him or her is at risk, while providers should also continue to work towards having parents involved, they said.

At a February meeting of the inter-agency task force on mental health and well-being, the proposal to give those above the age of 14 more leeway was brought up and acknowledged, ST has learnt.

When asked if the task force was looking into the proposal, a Ministry of Health spokesman said: “One of the focus areas of the task force pertains to strengthening services and support for youth mental well-being, including enhancing the accessibility and range of quality mental health services for youth and equipping parents with youth mental health and cyber wellness knowledge and skills.

“The task force is also looking into how to better support youth with mental health needs, including areas where consent may be involved. This is still being deliberated, and will be announced when the recommendations are finalised.”

The age of consent

Speaking to eight mental health treatment providers here, ST found there is a general rule that those under the age of 18 should seek parental consent before counselling or therapy can be carried out, but there is no clear legislation on this.

Under the Children and Young Persons Act, those under 14 years old are considered children, while those between the ages of 14 and 18 can be considered young persons.

But many of the providers noted that this general rule has been a deterrent for many youth seeking help. They pointed out that it could be the parents who directly contribute to the youth’s mental health distress, or that the parents do not believe in the need for mental health treatment.

Other reasons could be that the youth were not ready to tell their parents yet, as they were worried about their parents’ reactions.

“International studies show that 50 per cent of people who struggle with mental health issues start to show symptoms from age 14, so allowing those at that age to seek help more easily can only do good,” said Mr Asher Low, executive director of youth mental health charity Limitless.

Annabelle Kids clinical child psychologist Christine Kwek said that if, as a society, Singapore wants to make mental health support accessible to its young, then it should take steps to recognise mental health services as an additional service that can be accessed by them, with or without the need for parental consent. She added that from a developmental perspective, children from the age of 14 should be able to give consent for such services, as they are able to develop sufficient understanding.

Ms Bettina Yeap, principal counsellor at Care Corner Insight, noted that the Government has put in effort over the years to provide mental health services to youth, with the setting up of Community Resource, Engagement and Support teams (Crest) at social service agencies, among other moves.

“At the same time, if there is this parental consent clause that keeps them away, all the resources are out there, but they cannot access them due to the lack of consent,” she said.

Many agencies in the mental health sector, such as Care Corner and Singapore Children’s Society, require parental consent for treatment.

Others, such as Limitless, exercise a bit more flexibility by using the Gillick competency test when it is not possible to obtain parental consent.

The test, which originated in the United Kingdom, is typically used to assess whether a child under the age of 16 is mature enough to consent to medical treatment.

Providers noted that it comes down to each organisation’s internal guidelines and risk appetite.

Limitless said it also makes sure to understand why the young person is hesitant to seek parental consent.

“We identify the risk of parental harm – if they would traumatise the child, or if they are the problem. We also look for whether there is risk of self-harm, such as suicidal ideation or poor coping mechanisms such as the usage of drugs or alcohol,” said Mr Low.

Where possible, the agency works towards getting the parents involved eventually. “If parents are supportive and involved, a lot of good can come out of it. Treatment moves at a much faster rate because someone is helping them along.”

About 15 per cent of the agency’s cases are aged 14 to 18, and most do not have parental consent when they come in, said Mr Low.

Some providers also pointed out that young people between the ages of 14 and 18 are generally allowed to seek medical treatment at general practitioners, so extending this leeway to mental health treatment should not be that far a stretch.

Others highlighted that there is no legal requirement for parental consent for minors to undergo an abortion, which is largely seen as a more invasive procedure than mental health treatment.

ST ILLUSTRATION: CEL GULAPA

Tackling challenges

While the premise of such a move has its benefits, mental health providers that ST spoke to were also quick to point out several challenges.

One would be that parents could be unhappy with this change, as they may feel it is within their rights to know what is going on in their child’s life.

It is also important to assess that young people are suited to seek help independently.

Mr Low said his agency has turned away people who were found to be not competent according to the Gillick test matrix.

“We turn them away or require them to get consent because it is not safe to do treatment otherwise,” he said, adding that should something go awry, there is the issue of liability.

He suggested other professional safeguards that could be introduced by the authorities, such as a form of testing or assessment that could be used across the board to identify whether young people have the necessary competency.

Care Corner’s Ms Yeap suggested that a move to lower the age of consent could also be piloted at certain agencies first, to work out the potential pitfalls as well as safeguards that need to be put in place.

Annabelle Kids’ Ms Kwek added: “In the absence of clear and practical legislation or guidelines, mental health professionals may find themselves practising defensively if there is likely to be an argument about whether consent was validly obtained, possibly negating any benefit from lowering an age guideline.”

“The most effective safeguard will come from clear, practical and unambiguous guidelines on when a mental health professional may or may not provide mental health services to a minor without parental consent.”

Ms Vivyan Chee, deputy director of the Singapore Children’s Society and head of its Oasis for Minds Services, said the best interests of the child must be at the core of it all.

“A critical part of the discussion that must take place concurrently is the ability of the social service practitioners to be able to make accurate assessments, and to be able to explain things clearly such that the child or young person can make an informed consent.”

Another area that has to be looked into carefully is which mental health treatment services would come under this potential change.

For example, the providers that ST spoke to were in consensus that treatment for youth requiring the prescription of medication, such as antidepressants, should continue to require parental consent.

Ms Dorothy Lim, deputy head of the Singapore Association for Mental Health’s community intervention team, said there may be room to lower the age guidelines for youth seeking certain services such as mental health screening and assessment, counselling and basic emotional support, to encourage early help-seeking behaviour.

Parents a key part of equation

Providers were also in consensus that parents remain a key part of the equation in ensuring youth mental well-being.

As for the service providers ST spoke to that were not fully onboard with a lowering of the age guideline, their reservations mainly had to do with the importance of involving parents.

Ms Andrea Chan, who heads Touch Community Services’ mental wellness team, said there must still be a trusted adult involved. This could include parents, guardians, relatives or teachers.

But as much as possible, parents should be involved in the therapy process and know that the child is seeking mental health help, as research has shown that family involvement leads to better treatment outcomes.

“Clinical experience also informs us that in an event of safety risk, it is important to have someone who is responsible for the child whom we can reach out to,” she said.

“If we remove parents from the equation, then we are potentially removing a good support system. Instead, we should be aspiring to create a support community for youth to seek professional help and recover in the most conducive manner.”

Some resources that youth can tap

Annabelle Kids:

- Youth under 18 will require parental consent, but exceptions can be made sometimes, especially if parents contribute to the issues.

- In such circumstances, the clinic generally asks for a close family member above the age of 18 to acknowledge that the youth is seeking services with it.

Samaritans of Singapore:

- As SOS’ work focuses primarily on suicide prevention, the premise for its interventions is based on the suicide risk of the client, regardless of age.

Singapore Association for Mental Health:

- SAMH tries to get parental consent from those aged under 18, but for situations where the youth strongly refuses or comes from a family where doing so would jeopardise his or her safety, SAMH will assess the situation.

- It may ask the youth to obtain consent from or involve another trusted adult member of the immediate or extended family.

Singapore Children’s Society:

- Parental consent is sought before intervention is given to children.

Limitless:

- Ideally, parental consent is sought for those under 18, but for those who are unable to obtain it or will be put at risk by an attempt to obtain it, a Gillick competency test is carried out.

Care Corner:

- Parental consent is required for those under 18 to seek professional interventions such as therapy or counselling. However, mental health screening and basic emotional support are available to those between the ages of 13 and 25. Appointments for the services can be made through the Carey platform.

Touch Community Services:

- Parental or a trusted adult’s consent is required for those under 18 to receive mental health intervention services.

Schools:

- School counsellors will seek parental consent as part of their duty of care before counselling begins, said a Ministry of Education spokesman.

- While observing confidentiality of information is key for school counsellors to maintain trust with their students, school counsellors will also explain to students before the start of counselling the situations when they may have to bring in their parents for support. This applies when there are serious concerns about the student’s safety and wellbeing.

- All schools are resourced with at least one full-time school counsellor. In total, there are about 410 counsellors deployed.

Helplines

Mental well-being

Institute of Mental Health’s Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222 (24 hours)

Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444 (24 hours) /1-767 (24 hours)

Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

Silver Ribbon Singapore: 6386-1928

Tinkle Friend: 1800-274-4788

Community Health Assessment Team 6493-6500/1

Counselling

TOUCHline (Counselling): 1800-377-2252

TOUCH Care Line (for seniors, caregivers): 6804-6555

Care Corner Counselling Centre: 6353-1180

Online resources

mindline.sg

stayprepared.sg/mymentalhealth

eC2.sg

www.tinklefriend.sg

www.chat.mentalhealth.sg

carey.carecorner.org.sg

www.impart.sg