1 in 10 S’poreans does not have close friendships; most still make friends in person: IPS study

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

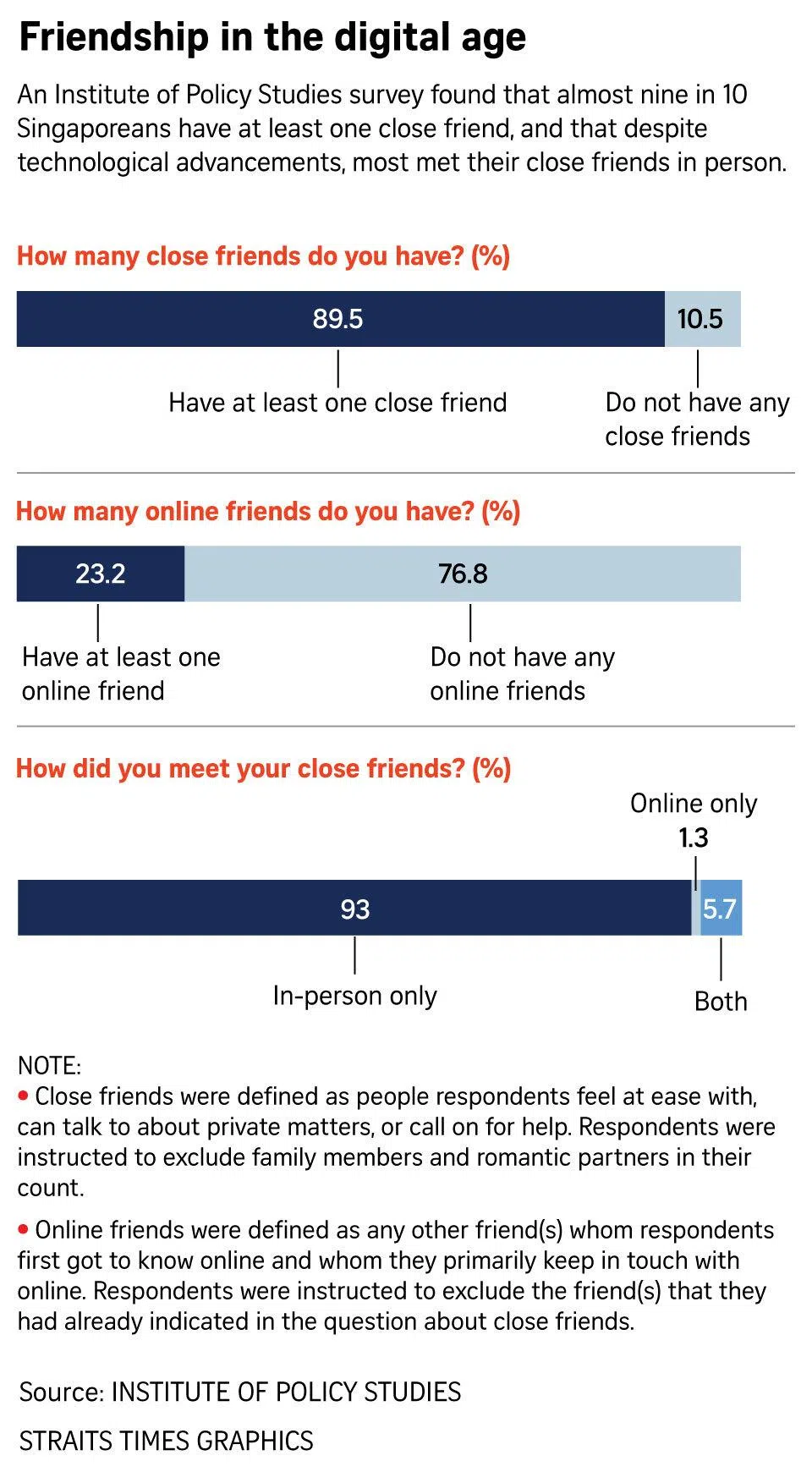

An Institute of Policy Studies study has found that 89.5 per cent of Singaporeans have at least one close friend – defined as people whom respondents feel at ease with and can talk to about private matters, or call on for help.

ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

SINGAPORE – Slightly more than one in 10 Singaporeans do not have close friendships, and despite technological advances, most still get to know their close friends in person.

These are new findings from a survey by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), which also found that among respondents, having diverse friendships across differences like age, gender and ethnicity is correlated with higher social inclusion and a sense of belonging.

The study, titled Fraternity and the Social Fabric in the Digital Age, also found that a minority of Singaporeans are turning to artificial intelligence (AI) for companionship, although most still said that interactions with AI do not replace close human friendships.

It polled 3,713 Singaporeans and permanent residents above age 21 in 2025. IPS’ social lab head Mathew Mathews released the findings during an online panel discussion convened by the think-tank on Jan 20.

The study found that 89.5 per cent of Singaporeans have at least one close friend – defined as people whom respondents feel at ease with and can talk to about private matters, or call on for help.

Respondents were asked to exclude family members and romantic partners.

It also found that 23.2 per cent of respondents have at least one online friend, defined as a friend whom they first got to know online and whom they primarily keep in touch with online.

Respondents excluded people they had already counted as close friends earlier.

More than nine out of 10 respondents said they first met all their close friends in person, with schools and workplaces the primary starting points for these connections.

The study found that younger people and those of higher socio-economic status (SES) are more likely to report having close friends, while those who reported having no close friends tended to be older and of lower SES.

Younger and more educated respondents are also more likely to have online friends. Of those aged 21 to 35, 43.5 per cent said they have online friends, compared with 20.6 per cent of those aged 51 and above.

Of respondents with degrees, 35.8 per cent said they have online friends, compared with 23 per cent of those with a secondary school education or below.

Half of those with online friends met at least one of these friends via social media, and four in 10 met via texting or messaging apps.

Respondents were also asked to break down the demographics of their close and online friends by gender, ethnicity, age, nationality, educational attainment and housing type. Online friendships are more diverse than close friendships across most of these attributes, the study found.

It also found that having a more diverse network of friends is associated with having fewer gaps in roles that friends fulfil, such as having people to confide in or spending time with.

Close online friends can also serve a similar mix of functions as offline friendships, the study said.

It concluded that people can turn to online friends for meaningful support, challenging existing assumptions that online friendships are superficial.

The study found that having a higher level of diversity is positively correlated with an increased sense of inclusion, increased social cohesion, trust in the community and increased civic involvement.

For example, a strong sense of inclusion is reported by 42.6 per cent of those with higher friendship diversity, compared with 30.9 per cent reported by those with a lower friendship diversity.

Respondents with more diverse friendships are also more likely to say they feel accepted and connected with others.

Indian and Malay respondents are more likely to have diverse friendships, compared with Chinese respondents, which IPS said reflected majority-minority dynamics and differing opportunities for contact.

Can AI be a friend?

The study also examined the emerging role of AI chatbots in Singaporeans’ social lives, and found that their usage is more prevalent among younger and higher-educated respondents.

AI chatbots are still primarily used to search for information or to help with work or school, but around one in 10 respondents also uses them for casual conversation, emotional support or mental health help.

Women are more likely to seek emotional support or mental health assistance from AI chatbots, with 13.8 per cent of women saying they have done so versus 7 per cent of men.

Younger respondents are also more likely to have done so, with 15.9 per cent of those aged 21 to 35 having done so versus 6.1 per cent of those aged 51 and over.

Most respondents remain cautious about AI chatbots, with 92.8 per cent of respondents saying people need to exercise more caution.

Most also said they do not view AI chatbots as a satisfying substitute for real-life interactions, with three-quarters of respondents disagreeing that it is possible to form “friendship-like” connections with such chatbots.

In the panel discussion on the results on Jan 20, National University of Singapore associate professor in computational communication Kokil Jaidka said AI chatbots offer interaction without obligation, meaning that people cannot create shared experiences or mutual dependencies, which help to bridge social development.

At the same panel, Ms Grace Ann Chua, the co-founder and chief executive of social organisation Friendzone, said digital platforms make it easier to go from strangers to acquaintances, but people often face barriers in going further.

“Participants share that they rely heavily on small digital signals, such as the speed of the reply, tone, messaging style and grammar to assess sincerity, safety, trust and comfort.”

This has also created a new source of tension, she said.

Her organisation, which runs programmes to connect people through structured conversations, is looking into designing support to better build people’s social skills and support “low-pressure” and repeated interaction among young people, so that friendship can grow over time.

More needs to be done to scaffold growing friendships outside the traditional pathways of work and school, panellists said.

Prof Jaidka, who studies friendship and social mixing, said her research shows that friendship is not just about openness or values, but instead requires sustained interaction, emotional effort and time.

These resources are critical as lives become more pressured and friendships are increasingly consolidated within familiar ties and class boundaries, she said.

This means it is necessary to design institutions and systems that reduce the effort to sustain friendships.

“If we care about cohesion, we need to treat friendship not just as an individual choice, but as an outcome shaped by social structure and institutional design.”