Free trade is usually seen as an economic issue, but its effects go much further and the global trading system has, over the past seven decades, essentially shaped the world as we know it today.

For Singapore, global trade is intertwined with the well-known story of its economic success. As a newly independent island with no hinterland, it got its start by attracting foreign investors to set up shop here, bringing much-needed jobs.

Today, globalisation continues to be the lifeblood of a nation with no significant domestic market and whose key sectors, such as shipping, depend on a free flow of trade.

A study by management consulting firm McKinsey & Company in March this year ranked Singapore tops in its inflows and outflows of goods, services, finance, people and data, relative to the country's size and population.

POST-WAR POWER STRUGGLE

Global events are also closely linked to trade.

-

US$16.5 trillion

World merchandise trade in 2015, down 13 per cent from US$19 trillion in 2014

US$4.7 trillion

World commercial services trade in 2015, down 4 per cent from US$4.9 trillion in 2014

0.6%

Singapore's Q3 2016 GDP growth compared with same quarter one year ago. The Q3 2015 GDP growth was 1.8 per cent. This is the weakest rate of growth since Q1 2009, when GDP shrank by 9.4 per cent year-on-year in the wake of the global financial crisis.

345

Number of trade restricting policies, such as restriction on imports from certain countries, adopted by Asia-Pacific economies in 2015, steadily rising from 28 in 2008

At the end of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union quickly became rival superpowers that sought to spread their opposing ideologies of capitalism and communism.

Trade with other countries became the US' way of cementing ties with its allies and projecting its influence abroad. In other words, America's economic agenda was an extension of its foreign policy.

As an April article in the Harvard Business Review said: "Together with military alliances, trade agreements helped bind together the major free-market democracies, their growing prosperity serving as an effective counter to the centrally planned economies of the Soviet Bloc and the People's Republic of China."

While the Cold War drew to a close in the late 1980s, economic integration did not diminish in importance. With the US victorious and the Soviet Union disintegrating, countries began worrying about what a world with a sole superpower would mean.

APEC'S U.S. STRATEGY

To guard against US unilateralism in a post-Cold War world, it was invited to join the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) when the trade organisation was formed in 1989, said Dr Malcolm Cook, a senior fellow at ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute. "It was also to keep the US involved in East Asia both at the strategic level and the economic level," he added.

The first Apec ministers' meeting, held in Canberra in 1989, was attended by 12 founding members. An Apec secretariat was set up in Singapore in 1993 and the first leaders' meeting was held in Seattle that year.

It became an annual affair for leaders to discuss freeing up regional trade. Other economies, including China, came on board over the next decade, bringing the membership to 21 in 1998.

Around the time of Apec's founding, China was about 10 years into its economic reforms, opening up to foreign investment.

The country was dubbed the factory of the world as manufac- turing jobs poured in, lifting millions out of poverty.

In 2001, China was admitted into the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Its membership was heralded as a move that would give the emerging power a stake in maintaining a rules-based world order and ensure its continued peaceful rise.

Institutions such as the WTO have provided a stable set of rules and norms that govern cross-border trade and multinational activity, and businesses have grown accustomed to that over the last 20 years, said Dr Davin Chor, an associate professor of economics at the National University of Singapore.

"This has given firms the confidence and certainty to expand into new markets, as well as adopt new production and sourcing arrangements that span multiple countries," he said.

The meetings of such trade organisations have also evolved into important forums for world leaders to discuss the state of global affairs, "particularly at times when we think the world has changed and we're trying to grasp what it means", said Dr Cook.

For instance, the 2001 Apec Summit was the first major international meeting after the Sept 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York.

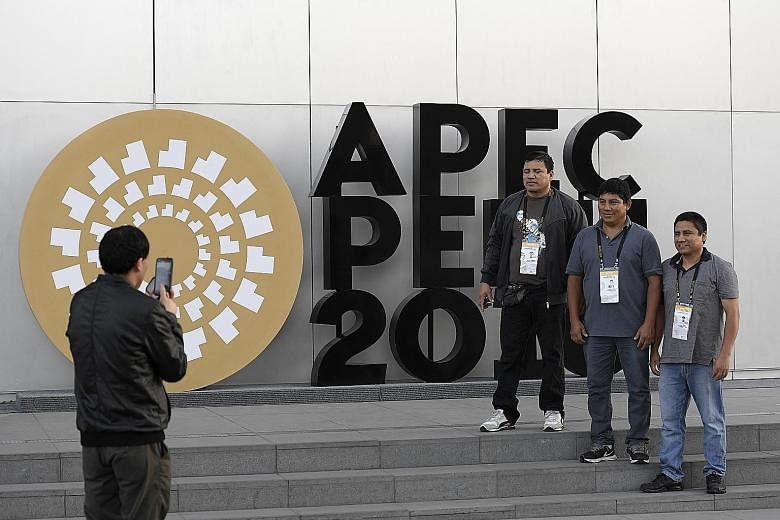

Similarly, last month's Apec Summit in Peru took place a week after a pivotal event in the US - when Mr Donald Trump became the US president-elect on an anti-free trade platform. This has fuelled anxiety that the US will detach itself from the world economy, and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said at the summit that this will risk unsettling the global trading system that it had helped nurture and foster over the decades.

For now, it is still too early to tell what direction the new United States leadership will take.

But if indeed the world's No. 1 economy turns inwards, such an outcome can only be negative for Singapore.