Separation shows Singapore was and still is a miracle

That period from Merger to Separation holds lasting lessons for Singapore. The following is an abridged version of the speech given by Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the launch of The Albatross File exhibition on Dec 7.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

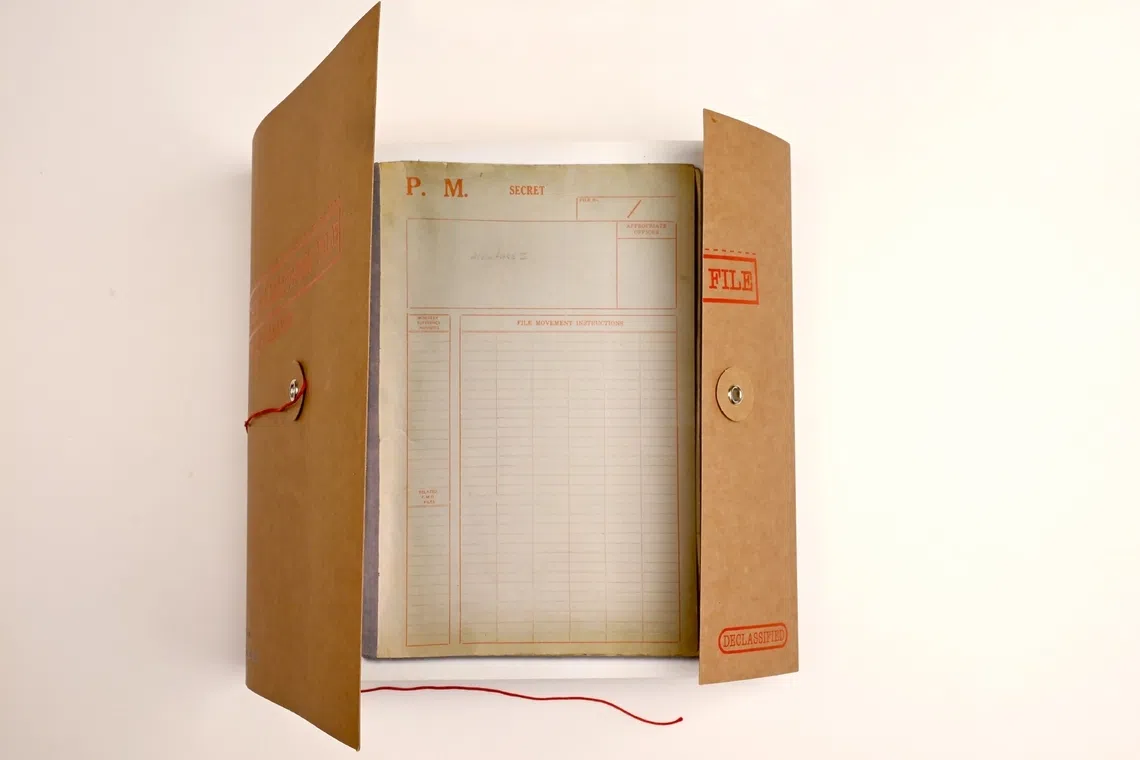

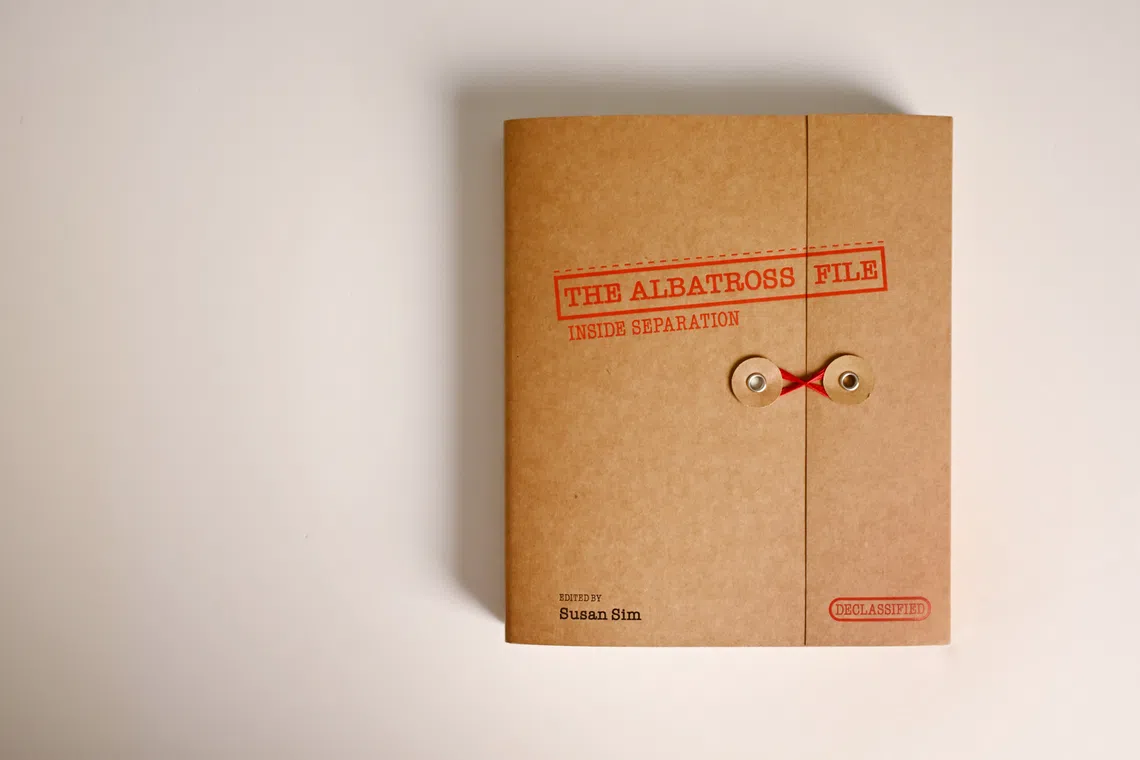

The Albatross File gives a vivid sense of what happened – a dramatic, blow-by-blow record of how Singapore came to separate from Malaysia.

ST PHOTO: STEPHANIE YEOW

The main contours of the story of Separation have long been well known. Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Malaysian Prime Minister then, recounted some of them in his 1977 memoirs, Looking Back. More information emerged as British, Australian and New Zealand diplomatic cables and reports of that period were declassified from the early 1990s onwards. Mr Lee Kuan Yew told the story from his perspective in his memoirs, The Singapore Story, relying on some of the same documents we are releasing today, as well as oral histories that he and his close colleagues had recorded in the early 1980s. Historians have also written about Separation. Professor Albert Lau’s definitive account, A Moment Of Anguish, appeared in 1998, the same year as Mr Lee’s The Singapore Story.

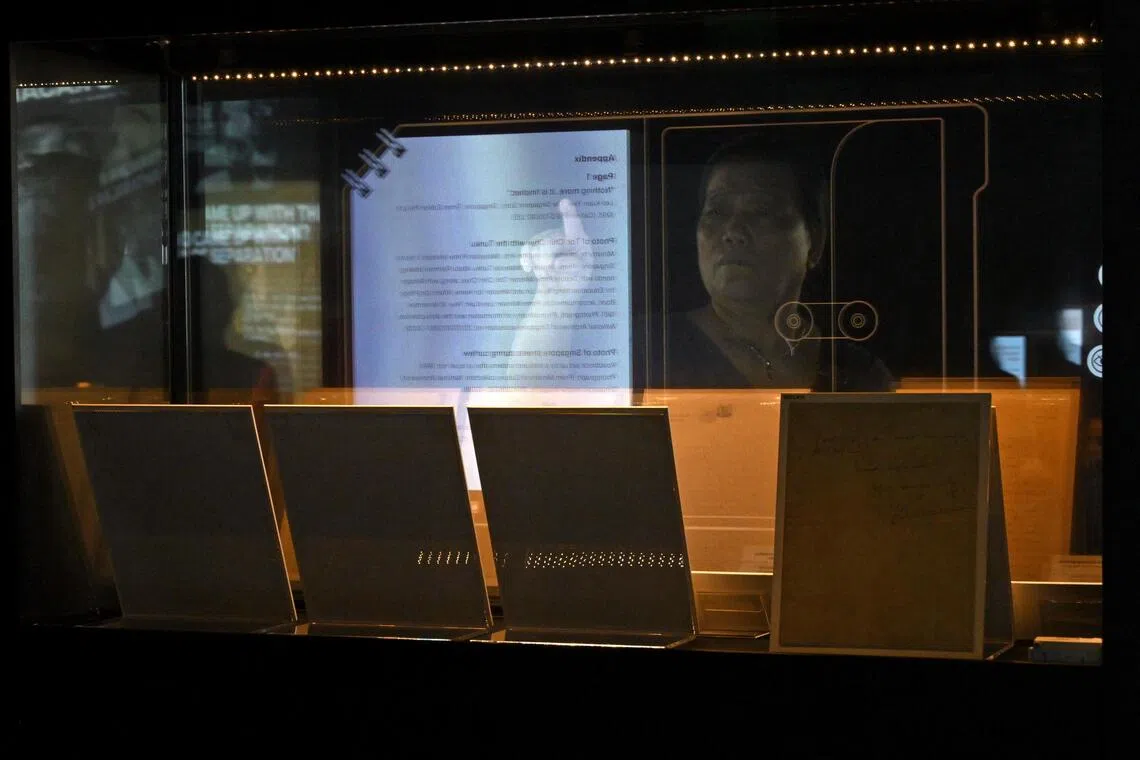

Still, the core of this book – The Albatross File

For a period the file was lost, before it was found in a storeroom in the Ministry of Defence (MINDEF) in the early 1980s. It was discovered by Dr Tan Kay Chee, a MINDEF officer who had then interviewed Dr Goh and some of our founding leaders for an oral history project on the political history of Singapore. Dr Goh relied on the file in his own oral history interviews, and read into the record several of the documents in the file. But for Dr Tan’s efforts and fortunate discovery, this precious record might have been lost to history, and we would have been all the poorer for it. The public first learnt of the existence of the file in 1996, after Dr Goh mentioned it in an interview with Dr Melanie Chew for her book Leaders Of Singapore.

The Albatross File gives a vivid sense of what happened – a dramatic, blow-by-blow record of how Singapore came to separate from Malaysia. There are incisive Cabinet papers setting out the fundamental issues at stake, analysing the strategic choices facing the different actors, and describing the state of political play after Merger with Malaysia. There are specific proposals on how Singapore might achieve a looser federation within Malaysia. There are succinct records of conversations with Malaysian leaders, and British and Australian diplomats. And there are the meticulous handwritten notes by Dr Goh of his meetings with then Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak and other Malaysian ministers to negotiate the Separation Agreement.

When I was prime minister, I decided that the Albatross File should be declassified and published. Together with the file, I also decided to publish relevant extracts from the oral histories of key participants involved in Separation, to bring together and put on the public record a fully documented account of this seminal event in our independence journey.

The core of this book – The Albatross File – is something that has not previously been put out. It contains important documents from the period, most of which have not been published before.

ST PHOTO: STEPHANIE YEOW

Was Singapore kicked out?

The key question concerning Separation is this: “Was Singapore kicked out by Malaysia, or did we seek Separation?” Originally, the prevailing view was: “We were kicked out.” The Tunku himself said at the time that the decision to kick Singapore out of Malaysia had been taken by him, solely.

But of course such an earth-shaking – and at that time, unexpected – outcome could not have had a simple or singular cause. The Tunku certainly was a decisive figure in Separation. But many factors forced his hand and led him to conclude that letting Singapore go was the best option, for him and for Malaysia.

Not least was the intense political campaign that Mr Lee and others in the Singapore leadership mounted to fight for a “Malaysian Malaysia”. As Dr Goh observed in his oral history, after the July 1964 race riots in Singapore, Mr Lee decided on a counteroffensive, “at great risk to himself”. “It was Lee’s policy,” Dr Goh said, “that if we were to get good terms out of (the Malaysian leadership), either total separation or a new working arrangement (within Malaysia), that they (the federal authorities) must find existing arrangements intolerable”.

So, Mr Lee brought enormous political pressure to bear on the federal government. There was the crucial speech in the Malaysian Parliament on May 27, 1965, where Mr Lee spoke in fluent Malay. The Tunku later described that speech as “the straw that broke the camel’s back”. And there was the Malaysian Solidarity Convention that Dr Toh Chin Chye and Mr S. Rajaratnam had initiated, which held rallies up and down the peninsula.

Those were very tense days. Mr Lee was aware that the federal authorities were considering arresting him, and that he was in grave peril. But as he told Britain’s High Commissioner to Malaysia Antony Head, he would not – he could not – back down. And as Mr Head noted, there was considerable truth and force in what Mr Lee said.

I was 13 then. One day, on the Istana golf course, he told me that if anything were to happen to him, I should look after my mother and younger siblings. Fortunately, as we later learnt, the British Prime Minister then, Mr Harold Wilson, had warned the Tunku that the UK would have to reconsider its relations with Malaysia if he arrested Mr Lee. So by the end of June 1965, the Tunku had decided that it would be best to “return Singapore to Lee Kuan Yew” instead.

The Tunku’s decision led to talks between Mr Razak and Dr Goh from mid-July onwards. Within three weeks, the Separation Agreement was drafted and signed, and Singapore was on its own. The albatross had finally loosened off our neck. As many historians have since characterised it, Separation was a mutually negotiated outcome.

But it was not the outcome that Mr Lee preferred. The Albatross File, as well as the oral histories, present evidence that Mr Lee was quite torn about Separation. Indeed, it was Mr Lee’s counter-strategy that forced the Tunku’s hand. And it was he who directed Mr E.W. Barker to draft the Separation documents, soon after Dr Goh’s first meeting with Mr Razak on July 15, 1965. But his aim was to strengthen Singapore’s position politically, so as to compel the federal government to grant Singapore greater autonomy.

Mr Lee recounted in his oral history and in his memoirs how in the talks between Dr Goh and Mr Razak, he had instructed Dr Goh to press for a looser constitutional rearrangement within Malaysia, and that Separation was to be an option only if Singapore could not get such a rearrangement. But Dr Goh came back to report that “Razak wanted a total hiving off”. Mr Lee accepted this, and took decisive steps that enabled Separation – which he called a “bloodless coup” – to happen.

Yet till the very end, Mr Lee was ambivalent. On Aug 3, 1965, when he was on holiday with the family in Cameron Highlands, Dr Goh telephoned him to report on his latest meeting with Mr Razak, and to confirm that Separation was on. In those days, calls to Cameron Highlands had to go through telephone operators, who mostly did not speak Chinese. So Dr Goh and Mr Lee spoke in Mandarin – not Dr Goh’s strongest language.

I remember that phone call. I was in the room at Cluny Lodge when my father took the call that afternoon, and I heard him tell Dr Goh in Mandarin: “This is a huge decision; let me think about it.” I did not know then what it was about, but it became plain soon enough. This was less than a week before Separation Day.

And even on Aug 7, 1965, after Dr Goh and Mr Barker had settled the Agreement with Mr Razak, Mr Lee saw the Tunku again to ask if they could have a looser federation instead – perhaps even a confederation. It was the Tunku who said flatly that it was over. I remember sleeping that night on the floor in the corner of my parents’ bedroom at Temasek House in Kuala Lumpur, before the family drove back to Singapore the next day. My father got up repeatedly throughout the night to write notes to himself.

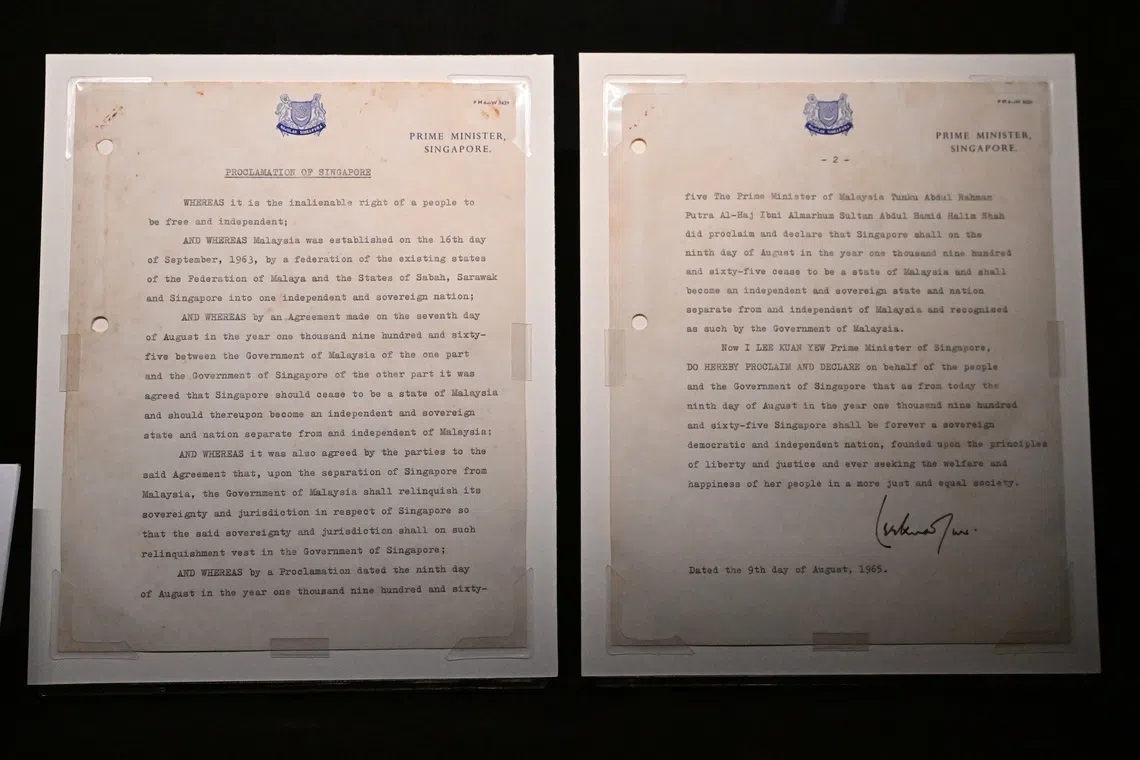

The Albatross File exhibition and book show how Singapore came to be “forever a sovereign democratic and independent nation”. It was hardly foreordained. It was - and still is - a miracle, says SM Lee Hsien Loong.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

This explains Mr Lee’s state of mind at Separation, and why at the press conference on Aug 9, 1965, he broke down, and spoke about “a moment of anguish”. My mother said in her oral history that that was the closest he came to a nervous breakdown.

Decades later, when Mr Lee was preparing his memoirs, he obtained Dr Goh’s permission to read his oral history. It was only then that Mr Lee discovered that contrary to his instructions, Dr Goh had, from the start, gone for a clean break, and never tried for the looser federation that Mr Lee preferred, and had instructed him to try for.

Mr Lee was so astonished that he made note of the exact time, date and place when he first learnt this. In the margin of the transcript of Dr Goh’s oral history, next to the passage where Dr Goh confirmed that it was he, and not Mr Razak, who had suggested Separation, Mr Lee wrote: “1st time read on 22 Aug ’94, 5.40 pm in the office.” Mr Lee had been trained as a lawyer. Mr Lee told some of the ministers about this, and his great surprise at what had really happened. He also spoke to me about it.

In 1977, when the Tunku sent Mr Lee a copy of his memoirs Looking Back, he inscribed on the flyleaf: “To Mr Lee Kuan Yew – The friend who had worked so hard to found Malaysia and even harder to break it up.” The first half of the sentence was true enough – Mr Lee had indeed worked hard to achieve Merger with Malaysia. But the second half was incorrect. Rather than a break with Malaysia, Mr Lee’s aim was a more secure and workable constitutional arrangement for Singapore within Malaysia.

Mr Lee felt torn. On the one hand, he felt deeply his responsibility to the Singaporeans whom he had persuaded to merge with Malaysia. On the other hand, he felt keenly his obligation to all those in the rest of the Federation, whom he and the Malaysian Solidarity Convention had mobilised to fight for a Malaysian Malaysia. It weighed heavily on him that he was abandoning and letting down the millions left behind when Singapore separated.

On his part, Dr Goh was convinced that Merger was doomed and that the Malaysian leaders themselves wanted us out. Hence, when he negotiated with Mr Razak, he pressed for total separation, assuring Mr Razak that Mr Lee would be amenable to the idea.

Thankfully, the stars were aligned. Within a few years of Separation, all our founding leaders – especially Mr Lee, and even those like Mr Rajaratnam, Dr Toh and Mr Ong Pang Boon, who had signed the Separation Agreement most reluctantly – concluded that Separation was the best thing that ever happened to Singapore. In this SG60 year, we are very glad that Dr Goh did what he did. Singapore has thrived and progressed far beyond anything the Founding Fathers imagined.

It was far from inevitable that events would turn out this way. In all likelihood, had Separation not been achieved, sooner or later the break-up would somehow have occurred – but most probably not as peacefully. The contradictions between the two societies were so profound that they could not have been resolved without a parting of ways.

SM Lee Hsien Loong greeting Ong Pang Boon at the launch of The Albatross File: Inside Separation and exhibition opening for The Albatross File: Singapore’s Independence Declassified, on Dec 7.

ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

Four key leaders

Four men were key to bringing Separation about. On the Malaysian side, the Tunku and his deputy Mr Razak. On ours, Mr Lee and Dr Goh.

If Tunku had not decided on Separation early, and remained firm in that decision, it would not have happened. Mr Lee said Tunku was decisive – not a “ditherer”. Dr Goh said he was a man “who can think in terms of big and serious things”.

In contrast, Mr Razak often changed his mind. Fortunately, he got along with Dr Goh, the two having known each other since their student days in London. And Mr Razak was friends with Mr Barker too – they had played hockey together in Raffles College. That basic trust between key figures on both sides, despite their deep political differences, enabled a peaceful Separation, unlike many other partitions and break-ups of the post-colonial era.

On Singapore’s side, Dr Goh was the “Architect of Separation”, as Mr Barker called him. In Dr Goh’s own words: “I’d had enough of Malaysia. I just wanted to get out. I could see no future in it, the political cost was dreadful and the economic benefits, well, didn’t exist. So it was an exercise in futility... It was a project that should be abandoned once you saw that it was worthless.”

Between July 15, 1965, when Dr Goh first met Tun Razak, and the early hours of Aug 7, 1965, when the Separation Agreement was settled, Dr Goh was intent solely on one goal: Singapore and Malaysia going their separate ways. He handled the negotiations brilliantly. He sensed his Malaysian counterparts wanted Singapore out too, and assiduously fed that desire. He adroitly avoided what he considered distractions, including the possibility of a looser federation. He stiffened Mr Razak’s resolve when Mr Razak wavered, reminding him of the painful alternatives to “hiving off”. He also committed Mr Lee to Separation by asking for a letter authorising him to negotiate constitutional rearrangements with Malaysian leaders. And he did not tell Mr Lee that he was not pursuing any of the other possible rearrangements that Mr Lee had instructed him to press for, except one – Separation.

Separation was not Mr Lee’s preferred outcome. But he supported Dr Goh in the negotiations, and supervised Mr Barker to include key clauses in the Separation documents. He went to great lengths to persuade all his ministers to sign the Separation Agreement, so there was no Cabinet split, and independent Singapore started out with a strong, united leadership team. At the strategic level, it was the political pressure that Mr Lee orchestrated, the international stature that he had built up, and the courage and leadership that he showed, which compelled the Tunku to let Singapore go.

Lasting Lessons

Had Mr Lee shown any signs of being afraid, or being willing to bend, we would have been rolled over. Singaporeans saw Mr Lee stand up to the radicals in UMNO – the “Ultras”, as he called them. They knew he could not be intimidated. They realised that he was prepared to risk all, including his life, to secure their future. It was through this experience of Merger followed by Separation that Mr Lee and the People’s Action Party (PAP) solidified their support among our Pioneer Generation.

Mr Lee was not the only Singapore leader to show courage in the crisis. In the week before Dr Goh’s first meeting with Mr Razak, two significant events happened. The meeting was on July 15, 1965, but first, on July 8, 1965, several key PAP ministers – Dr Toh Chin Chye, Dr Goh, Mr Barker and Mr Lim Kim San – held a press conference to declare that they stood with Mr Lee, and would not “quietly acquiesce” if Mr Lee were detained.

Then, on July 10, 1965, there was a by-election in Hong Lim constituency. Singapore’s leaders believed the federal authorities had engineered this by-election to test the PAP’s support. The PAP had lost Hong Lim twice before. This time, it fielded Mr Lee Khoon Choy as its candidate. It campaigned on the issue of a Malaysian Malaysia. And Khoon Choy won, with 60 per cent of the votes.

These two events surely convinced the federal leaders, especially the Ultras, that they could not cow or suppress Mr Lee and his team, and hence they were better off with Singapore out of the Federation.

Trust in Government, and in the political leadership in particular, is founded on the people knowing their leaders will always have their backs. That is one important lesson from our two years in Malaysia. Our founding leaders won the right to govern because Singaporeans were convinced that Mr Lee and his team could not be intimidated into compromising Singapore’s interests. His successors have not forgotten this lesson. No Singapore PM has ever allowed any force or power, whether foreign or domestic, to intimidate us into compromising our national interest or sovereignty.

The other enduring lesson is never to take our racial and religious harmony for granted. From September 1963, when the PAP won all three Malay-majority seats in the general election, to July 1964, when Singapore was engulfed in race riots, was only 10 months. Within this brief period, the Ultras succeeded in sowing deep distrust between the Malays and Chinese.

Asked for his most vivid memories of the two years in Malaysia, Mr Lee said: “First, how easy it is to arouse communal passions. That once you get people excited over race differences, language differences, religious differences, and they start butchering... or maiming each other, distrust and fear seeps through the whole community. And I watched with despair and dismay that so much work to bring the races together (over) so many years could be wrecked in such a short time.

“So when I look at the new housing estates where we’ve mixed them all up, I have never allowed myself to forget that this air of interracial harmony and trust is very fragile. It can be snapped, broken, smashed... The dynamics of communal politics or communal politicking will override reason and logic.”

We separated from Malaysia because of identity politics based on race and religion. We will never allow race or religion to break up Singapore.

The proclamation of Singapore signed by Mr Lee Kuan Yew on Aug 9, 1965, seen at the exhibition opening for The Albatross File: Singapore’s Independence Declassified.

ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

Many Singaporeans today look at Separation as a distant memory. Indeed, they wonder why some of our leaders were so conflicted about leaving Malaysia. But at the time, when the issue was live and the stakes were huge, it was far from obvious that Singapore should be independent, or had such a future.

For those who lived through those times, each step was uncertain, each negotiation harrowing, each decision wrenching. Neither our founding leaders nor the people they led could be certain Singapore would survive, let alone thrive, as an independent island-nation. As Mr Lee once said, he was glad he did not have to live through again the 23 months from Merger to Separation. He wasn’t sure we would be so lucky as to emerge intact again from those terrifying times.

I encourage Singaporeans, young and old, to experience through this book and exhibition how Singapore came to be “forever a sovereign democratic and independent nation”. You will realise it was hardly foreordained. It was – and still is – a miracle.

The full speech can be found

here

.