Singapore built a nation underpinned by public health, but new threats loom

Sixty years after independence, Singapore has come a long way from the time it battled malnutrition and poor hygiene. Very different enemies lurk in the future.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Healthier SG, a major national health reform, is pivoting the system from treating sickness to promoting wellness.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The year is 1965.

You wake to the clatter of metal buckets, as night soil collectors begin their rounds to empty the outdoor latrine shared by four households. The stench is overwhelming, mingling with the acrid smoke from nearby charcoal fires where a street food vendor fries dough fritters in reused oil.

You send your barefoot child off to school with a coin for lunch – likely a bowl of watery porridge or cheap fried noodles. At the school tuckshop, there is little green in sight, mostly fried snacks and sugary drinks. Most of the children in school do not own a toothbrush, and many already suffer from significant tooth decay by the time they are seven.

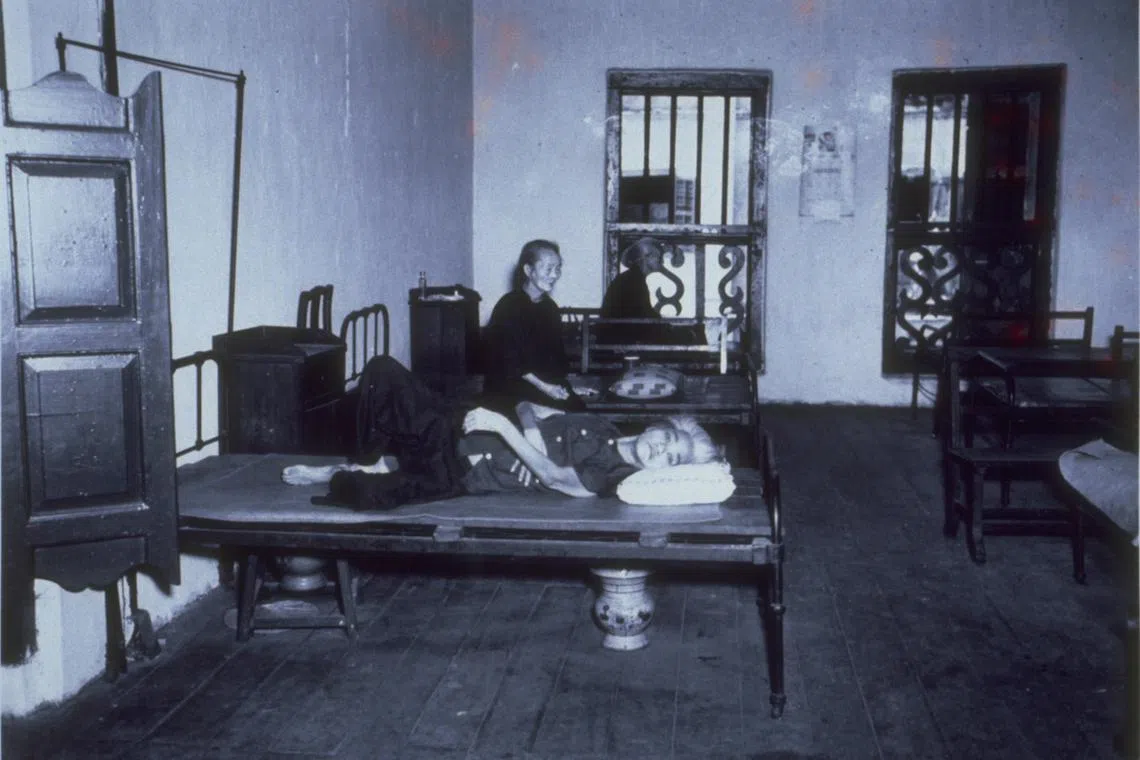

Passing your neighbour on her way to the “death houses” in Sago Lane – shophouses where the terminally ill are taken to die – you learn that her mother has tuberculosis. Her daily visits provide her mother essential sustenance, as there is otherwise little food offered to the occupants.

At the shipyard where you work, news circulates that a night-shift worker has lost a finger in a drilling accident – the third such incident in a month. Workplace safety is minimal, with no established protocols or protective gear.

This was the public health reality for the average Singaporean at independence.

Singapore in the 1960s faced the full weight of post-colonial neglect. Malnutrition and poor sanitation were widespread, and infectious diseases such as typhoid, tuberculosis and gastroenteritis were common causes of death.

The healthcare system was under-resourced, with insufficient doctors, nurses and clinics. It also lacked coordination across public services.

Health at the heart of the nation

Despite these harsh conditions, Singapore’s leaders recognised that public health was not merely a social need, instead it was the foundation for national development. Priorities included clean water, proper sewage systems, pest control, food safety, vaccinations and safe working environments.

Systematically, the government established the physical infrastructure and policy regulations to eliminate key threats to the health and wellbeing of the people.

Mass public housing projects by the Housing and Development Board replaced overcrowded slums with flats equipped with running water, modern sanitation and centralised garbage disposal. Proper sewage infrastructure supplanted the bucket latrine and night soil collection system.

Hawker centres were constructed to rehouse street food vendors, incorporating proper waste disposal and hygiene regulations. Rodent infestations and unsafe food practices were addressed through a combination of enforcement and education.

The death house at Sago Lane where terminally ill inmates are left to die.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The Factories Act of 1973 established national standards for protective equipment, accident reporting and safety training, ensuring safer working conditions across the different emerging industries.

The national School Milk Scheme addressed malnutrition by providing essential nutrients to generations of children. Smoking bans, initially in buses and cinemas, were progressively extended. This, along with other measures, enabled Singapore to have one of the lowest smoking rates in the world today.

Mandatory tooth-brushing drills in primary school, using disclosing tablets to highlight unremoved dental plaque, helped instil lifelong oral hygiene habits.

Even the concept of dying with dignity was addressed. Policies expanded palliative care and community-based support for the terminally ill, replacing the death houses of old with proper care facilities.

These stories illustrate that health is never just about the doctors and hospitals, but also about housing, education, clean water and workplace safety.

A nation’s development is intrinsically linked to systematic investments that first protect the health and wellbeing of the people, enabling them to pursue education and work opportunities to further build the nation.

A different challenge now

As Singapore grew wealthier and more educated, the public health challenges evolved.

Today, the nation grapples with complex health issues linked to societal, lifestyle and demographic changes. Although life expectancy has reached 84 years (it was 67.5 years in 1965), many spend the last decade of life managing chronic illnesses.

Conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cancer and heart disease are increasingly appearing in younger age groups, often because of sedentary lifestyles, poor diets and stress.

Mental health has become a major concern. The pressures of success, balancing work and caregiving as well as meeting peer and societal expectations weigh heavily on many. Young people struggle silently with anxiety and depression, while older individuals face loneliness. Unlike the old days where ailments were mostly physical and visible, today’s struggles are often hidden behind closed doors and phone screens.

Managing long-term diseases invariably places sustained pressure on healthcare services, drives up medical costs and increases demand for trained healthcare workers. These trends are further compounded by an ageing population, bringing challenges of social isolation, financial strain and a looming shortage of caregivers.

This is why Singapore’s current health policies reflect these shifts. Healthier SG, a major national health reform, is pivoting the system from treating sickness to promoting wellness. Family doctors are now frontliners in prevention. Seniors are encouraged to enrol with a regular GP, receive screenings and stay active through community programmes.

The National Mental Health and Well-being Strategy recommends embedding additional support into schools, workplaces and the community.

Efforts are also under way to design cities conducive to walking, cycling and social connection – because good health isn’t just about medicine, it’s also about the environment we live in.

Future health threats

Looking ahead, Singaporeans’ health will be threatened by both internal and external forces.

Domestically, the demographic transition is sobering. Very low fertility rates and a rapidly ageing population point to a future with fewer young workers supporting a growing elderly cohort. Meeting the care needs of this population will require innovations in eldercare, or a heavier reliance on migrant workers – the former likely involving technology and higher costs, and the latter becoming less tenable amid geopolitical uncertainties.

We must also rethink our physical infrastructure to accommodate an ageing population. From age-friendly housing and accessible public transport to workplace redesigns for older workers, urban planning must now centre around accommodating an increasingly aged society.

But it is the external threats – what I term as global threats – that are going to loom even larger.

Climate change and biodiversity loss pose direct health risks to our people through heat-related illnesses, more frequent and prolonged episodes of dengue outbreaks and respiratory conditions caused by air pollution. They also threaten food security when entire natural ecosystems collapse, and drive the emergence of new zoonotic diseases with pandemic potential.

Precisely because the world is now in a pandemic era, we anticipate there will be increasingly frequent outbreaks of new infectious diseases. As Covid-19 demonstrated, such events can devastate lives and livelihoods alike.

Even familiar pathogens are becoming more dangerous. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – where bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites evolve to resist existing treatments – threatens to undo decades of medical progress.

AMR could render once-treatable infections deadly again. Routine operations, cancer chemotherapy and management of chronic disease complications heavily rely on antibiotics. When these drugs no longer work, the foundation of modern medicine collapses. Combating AMR requires stringent regulatory stewardship, new drug development and global cooperation.

We’ll always need foresight

The health challenges of the next 60 years will be more complex and more global than ever before. They will defy traditional sectoral boundaries and cannot be tackled by the health sector alone.

The principle of “health in all policies” must be deeply embedded in Singapore’s governance.

Decisions on transport, education, housing, urban planning, finance and trade all have health implications. Singapore’s future leaders must continue to prioritise health and human capital at the core of policymaking across government.

At the same time, many serious threats are transnational. Singapore must strengthen its role in global health diplomacy – actively shaping international norms, contributing to multilateral bodies like Asean and the World Health Organisation as well as addressing root causes through collaborative global action.

Just as visionary leadership, pragmatism and long-term planning underpinned Singapore’s early public health successes, the same foresight is now needed to navigate an increasingly uncertain and volatile future.

Singapore’s public health journey is far from over. But if history is any guide, it is a journey that the nation must be prepared to continue – boldly, and with foresight.

Teo Yik Ying is vice-president for global health and dean of the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at the National University of Singapore.