S. Rajaratnam: Recounting the life and work of one of Singapore’s core founding fathers

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Follow topic:

Old Guard member S. Rajaratnam played a pivotal role in Singapore’s history, and his contributions are covered in the second volume of a biography by former journalist and ex-MP Irene Ng out in July.

These edited extracts from S. Rajaratnam, The Authorised Biography, Volume Two: The Lion’s Roar, published by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, touch on the 1964 racial riots, the Separation in 1965, and the crafting of the national pledge, as well as his visit to China in 1975, the first by a Singapore leader since independence.

How Raja handled a riot in the face of ‘arsonists playing firemen’

As he listened to the frantic voice on the phone, S. Rajaratnam realised that his greatest fear had come to pass. As one of the chief architects of Singapore’s independence, he had experienced some tough situations – but this was the worst tragedy to befall his country in his five years in politics.

It was July 21, 1964, barely a year after Singapore merged with Malaya and two Borneo states, Sabah and Sarawak, to form Malaysia in September 1963.

The voice on the phone that late afternoon was that of his close colleague Othman Wok, the social affairs minister. Othman had looked up to Raja, as the culture minister was usually known, since their journalism days in the 1950s. Raja had led the Singapore Union of Journalists as its president with Othman as his deputy.

On 1965 Separation: ‘My dreams were shattered’

Raja looked over the Separation Agreement that Lee Kuan Yew had handed him, and said: “I will not sign it.” He could not bow to the decision to split Singapore from Malaysia. And he would not. It was Aug 7, 1965, and he was enduring the most painful hours of his political life.

Lee had broken the news to Raja as soon as he strode into Temasek House in Kuala Lumpur just past 8am. Raja had rushed up after being summoned by a phone call from Lee in KL at about 1am.

Upon arriving at the two-storey bungalow, Raja found Lee in a “very agitated frame of mind”. Without any pleasantries to ease the blow, the PM laid out the Tunku’s proposals. They sounded to Raja like an ultimatum mixed with a threat: either leave Malaysia willingly, or be responsible for a racial bloodbath.

National pledge: Putting Singapore’s essence into words

One February day in 1966, Raja sat in his spartan office in City Hall and settled into his rich world of ideas. Each day brought new conflicts and decisions. But few were more demanding on Raja’s creative faculties than the task at hand – distilling the essence of Singapore’s ideals and identity into one sentence.

The exercise had begun in response to a request for help from education minister Ong Pang Boon. With Singapore’s independence, an important part of Ong’s brief was to inculcate national consciousness among the half million pupils who made up over a quarter of the country’s population.

In his letter headed “Flag Raising Ceremony” dated Feb 2, 1966, Ong sought Raja’s advice on the wording for a students’ pledge of allegiance to the flag. Furnishing two versions drafted by staff, he asked Raja for his comments and for “whatever amendments you wish to suggest”.

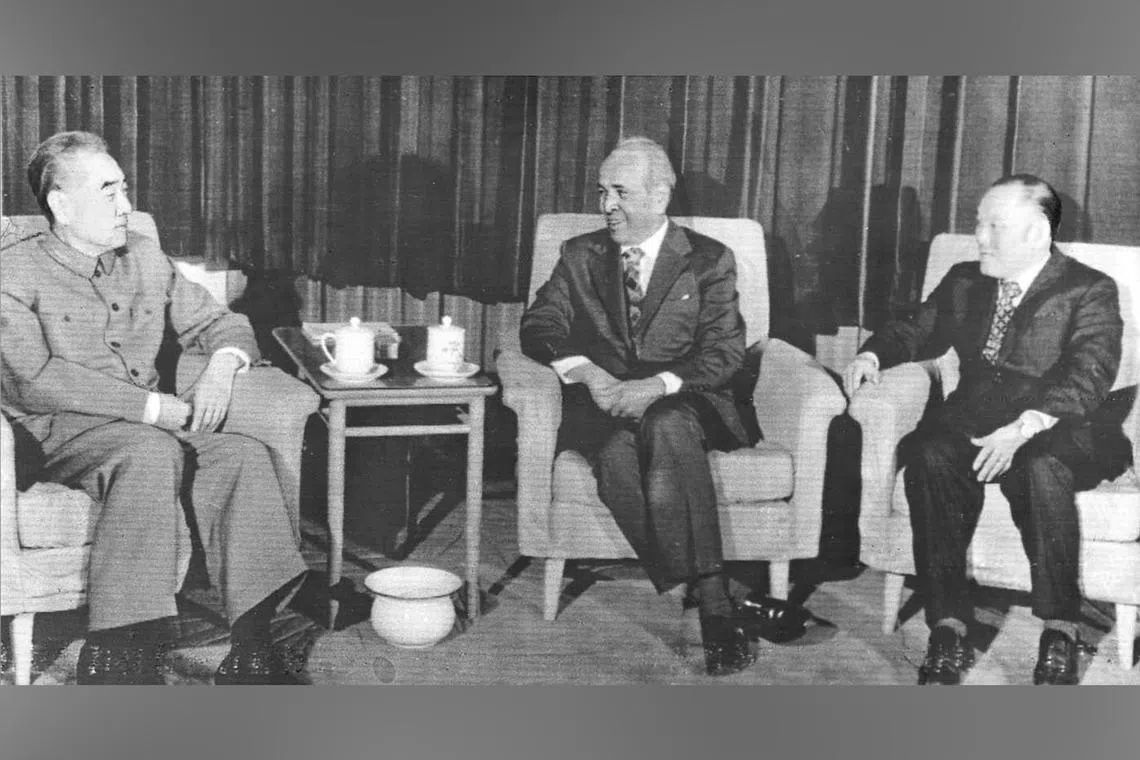

Like Marco Polo: When Raja met Zhou Enlai

It was past 9pm, Sunday, March 16, 1975. Raja, the first Singapore leader to visit China since Singapore’s independence, was in a Chinese-made Red Flag limousine, curtains drawn, being whisked through the near-empty streets of Peking to an undisclosed place. He was not told where it was exactly, but what he knew was enough. He was on his way to meet the ailing Chinese premier Chou En-lai (Zhou Enlai) at a place that the Chinese had described as a hospital.

The late-night arrangement was not on the programme when he arrived in Peking with a four-man delegation three days earlier. In fact, he was told about it only that very evening over a dinner, after rounds of intensive talks with Chinese foreign minister Chiao Kuan-hua (Qiao Guanhua).

There were several unexpected turns during Raja’s nine-day goodwill mission from March 12 to 21, but none as momentous as his dialogue with Chou. It was a landmark event in the tumultuous – and currently stalled – state of Sino-Singapore relations. It would in fact end a decade of official sullen silence and open a new era in relations between the two countries.