Navin Rajagobal, For The Straits Times

Roots of international law in 1603 incident off Changi

In recent weeks, stories about Singaporeans' knowledge of their history (or lack thereof) have been prominent in the media. Here is one event that Independent Singapore should remember.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

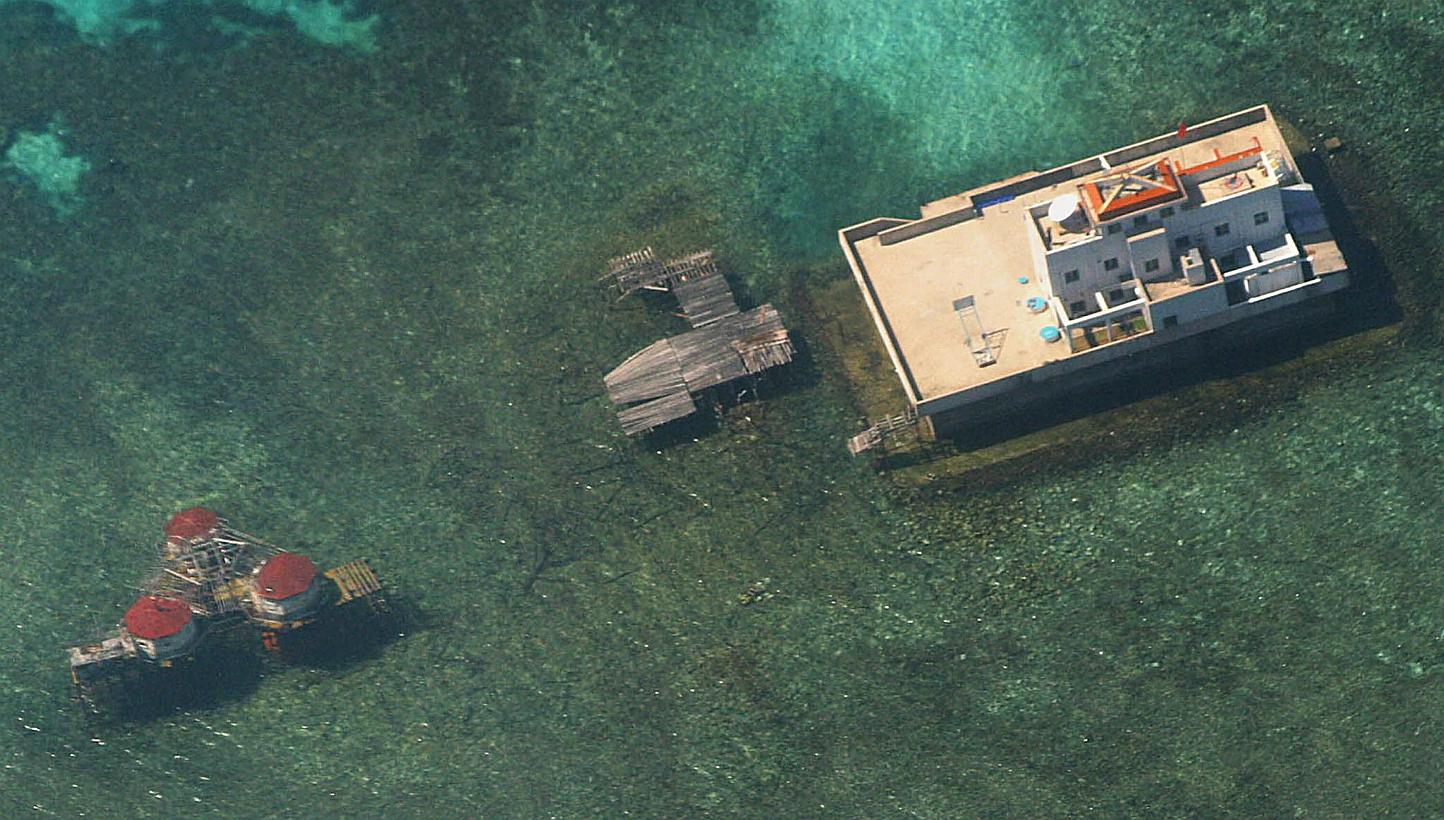

Chinese-built structures in the disputed Spratly Islands. Some observers have suggested that China's "nine dashed lines" map, which seems to enclose the busy sea lanes of the South China Sea, harks back to the mare clausum (closed sea) principles favoured by the Portuguese in the 1600s.

PHOTO: AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

I would like to take this opportunity to highlight an important historical incident with lasting global repercussions that took place very near our island.

Few residents of Singapore would be aware of this event, and I would not blame them for this, because it occurred in 1603.

This Wednesday, Feb 25, marks the 412th anniversary of the event.

The incident I refer to happened off Singapore's upper east coast, near Changi. The Santa Catarina, a Portuguese merchant ship captained by Sebastian Serrao, was attacked and seized by smaller ships commanded by Jacob van Heemskerk from the Netherlands.

The Santa Catarina and its precious cargo of silk, porcelain, camphor and other spoils were swiftly dispatched to Amsterdam. When these were auctioned, the proceeds amounted to about £300,000, a princely sum in 17th-century northern Europe.

Naturally, the Portuguese wanted their treasure back, while many in the Netherlands were troubled by the legality and morality of the seizure.

The Dutch wished to disrupt Portuguese domination of Europe's trade with Asia as part of their continuing conflict with their former overlord, Habsburg Spain, which ruled Portugal.

But van Heemskerk's mission to Asia, meant to promote trade, was not explicitly authorised to attack Portuguese shipping, and so the assault on the Santa Catarina could be construed as piracy.

In response to the brewing domestic and international scandal, van Heemskerk's sponsor, the United Amsterdam Company, hired an up-and-coming young lawyer named Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) to draft a paper that would defend the seizure of the Santa Catarina.

Grotius shrewdly justified the incident off Changi by claiming that van Heemskerk's action had lawfully challenged Portugal's unfair monopoly on commerce with Asia.

He explained that the Portuguese had not only blocked the Dutch from Asian ports and markets, but also used unlawful force against other Europeans and Asians to maintain their domination of the Asian trade. Hence, by seizing the Santa Catarina, van Heemskerk had engaged in a "just war" to punish Portuguese transgressions and defend freedom of navigation between Europe and Asia.

Grotius' views on the Santa Catarina incident, published as Mare Liberum (The Free Sea) and De Jure Praedae (On the Law of Prize and Booty), and the opposing arguments generated by his views, became the spark that ignited the development of modern international law. Some scholars refer to this as the "Grotian Moment".

For example, Grotius' affirmation that the high seas were international territory and that any country was free to use it for maritime trade became a cornerstone of international law relating to oceans.

This principle was eventually codified in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), which is widely recognised as a "constitution" for oceans and seas.

In addition, Grotius' assertion that war is justifiable only when it serves a right (just war theory) became a guide for international law relating to the use of force and self-defence. This was later enshrined in the United Nations Charter. The charter justifies use of force by states only for self-defence or if endorsed by the UN Security Council in the interest of international peace and security - in other words, for the right reasons rather than for aggression.

Not surprisingly, Grotius is considered to be the "father" of international law or at least one of its earliest pioneers.

The connection to Singapore initially appears to be a case of incidental geography. But there is more to this story, because van Heemskerk did not act alone. The resident population helped him.

The Santa Catarina, which was sailing from Macau to Malacca, was anchored off eastern Singapura. The local authority at the time, Johor-Riau, had been founded by evacuees fleeing the Portuguese conquest of Malacca in 1511. Therefore, Johor-Riau was happy to ally with van Heemskerk and provided intelligence, combatants and rowing yachts to carry out the raid.

In fact, Raja Bongsu (later Sultan of Johor-Riau) had sought out van Heemskerk in Pattani and invited him to sail to Singapura to set a trap for the Portuguese. He and other native leaders were probably on the Dutch flagship, the White Lion, during the raid on the Santa Catarina.

The battle began at about 8am on Feb 25, 1603. The raiders focused on the Santa Catarina's sails so as not to damage the cargo or sink the ship. Even so, the confrontation was fierce, with at least 70 casualties.

By 6pm, the Portuguese surrendered the Santa Catarina in return for safe passage to Malacca, which was granted.

The Netherlands' alliance with the local authority was a major plank of Grotius' legal justification for the seizure of the Santa Catarina. By supporting the locals in their struggle against Portuguese Malacca, van Heemskerk was not a pirate, but an agent of Johor-Riau.

Singapura, of course, went on to become a major international hub for trade and shipping. Freedom of navigation, access to global markets and free trade - concepts that would have been familiar to Grotius - are now key elements of Singapore's foreign policy, as they have been crucial for the island-state's economic success.

Recent developments such as the South China Sea territorial and maritime disputes have also highlighted the importance of international law relating to the seas.

Some observers have suggested that China's "nine dashed lines" map, which seems to enclose the busy sea lanes of the South China Sea, harks back to the mare clausum (closed sea) principles favoured by the Portuguese in the 1600s.

This would be contrary to the mare liberum (free sea) principles championed by Grotius after the Santa Catarina incident and subsequently encapsulated in Unclos.

I am therefore of the view that Independent Singapore, as it turns 50 this year, should remember the 412-year-old Santa Catarina incident, since it spurred the development of international law, and it happened just off Changi.

stopinion@sph.com.sg

The writer is director, faculty affairs, at Yale-NUS College and former deputy director of the National University of Singapore Centre for International Law.