Parents want well-read kids, but are they themselves reading?

Books power learning, but parents too need to embrace this ethos of reading for child development to really take flight.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Reading should be done preferably with a physical book rather than an iPad.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Twice this month, I was startled by the cleverness and literacy of a very young child.

On both occasions, I was on public transport and was so taken by their precociousness that I simply had to ask the parents how old the children were.

First was a little girl on the MRT, eyes bright as buttons, chatty with strangers. When I asked her her name, she said Emily. She then proceeded to spell it out for me, letter by letter.

I was speechless. At that same age, growing up in Kampong Potong Pasir in the 1950s, I couldn’t even say my own name in full, let alone read or spell.

My second encounter was with a little boy, face infused with brightness, at an LRT station in Punggol. He pointed to the signboard and read it out to his father: Punggol Point. My jaw dropped.

Both were only three years old.

These episodes have reinforced my conviction that our children today have an advanced level of intelligence and maturity that my Merdeka Generation did not possess. Though they might have been reciting from memory, there is still some measure of literacy. Modern children have a greater opportunity for learning, and we should take advantage of this.

It is incumbent on us as parents, family members and friends of those with children to nurture this delightful spontaneity in them and their love for knowledge.

Family elders and parents must nurture a love of learning

Children are curious spirits, constantly yearning for adventure and spoiling for a new discovery. Learning comes naturally to them, but reading takes this further by opening up the mind to new possibilities and cultivating a sense of imagination.

Research shows reading to children at a young age helps them expand their vocabulary, and develop stronger language skills and abstract thinking.

Being immersed in a favourable home environment packed with knowledge boosts literacy. A 2018 Australian National University study of 160,000 adults around the world found teenagers aged 13 to 14 who grew up in a house full of books had literacy rates comparable with university students with few books at home

The recent 2022 Singapore Writers’ Festival (SWF)

New Zealand young adult novelist Chloe Gong, whose 2020 debut novel These Violent Delights had been a New York Times bestseller, spoke to a full house during both of her speaking sessions at the Victoria Theatre then. The chamber was packed with hundreds of reading enthusiasts who later rushed to the pop-up bookstore to make their purchases and get their books signed.

“Young people are reading and writing, and engaging with texts more than ever before,” SWF director Pooja Nansi told local media last November.

“The #Booktok trend on social media… has led to a revival of reading culture. People are bringing poetry to every medium possible. Just look for a poet on Instagram and you’ll see that their followers are in the tens of thousands.”

But do we ourselves read?

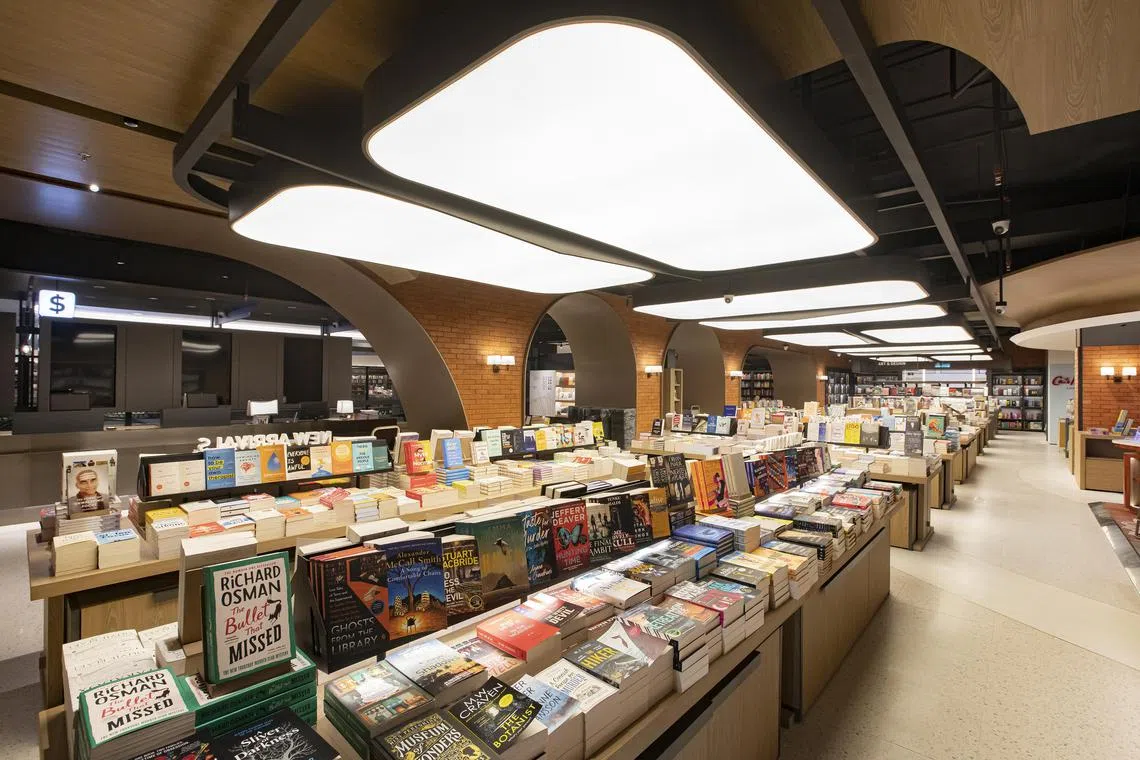

But if we want our children to read, are we role-modelling exemplary behaviour? Are Singaporean parents themselves reading? The latest opening of a 70,000 sq ft Eslite bookstore

Eslite bookstore in Kuala Lumpur’s The Starhill is the Taiwanese brand’s first in South-east Asia.

PHOTO: ESLITE SPECTRUM

Our track record might look dismal at first sight. We are a country where many big bookstore names such as Borders and MPH have shuttered over the past decade, and others like Times and Popular are filling shelves with stationery and toys rather than books. Apart from Kinokuniya, people are hard-pressed to recall another major bookstore chain.

Perhaps we are swopping bookstores for libraries? Our numerous national libraries located downtown and in heartland malls of convenience are typically packed with young readers and families. On the online National Library Board (NLB) app Libby, books are always going out on loan and can have long, snaking digital reservation queues.

In that sense, our dearth of bookstores speaks more to the success of our public libraries. It is a tragic trend, but does not herald the demise of reading.

Basic economics too seems to explain our bookstore desert situation. Retailers, including booksellers, have long lamented the high costs of rental and staffing making it challenging for big bookstores to stay solvent in Singapore. Let’s hope the second-hand gems in Bras Brasah continue to thrive.

Perhaps there is some way of reducing rentals and reviewing goods and services tax on books like in countries such as the United Kingdom, so that costs do not deter people from investing in reading.

Our love for the practical gets in the way

Any form of reading which we engage in has its positive benefits, whether it’s simply for serious facts, information or for light entertainment. The more the reader takes in information from the book, the more the reader is using the left brain, involving logic and analysis.

In reading fiction, however, the language and scenarios employed by the writers give space for the reader to use his imagination and expand his mind in a different way – functions that exercise the right brain. This is why reading fiction has a different role compared with pragmatic or functional reading. The reader interacts with the written word. This interaction sparks exploration and creativity – a paramount reason to encourage children to read fiction.

Still, a deeper look at our national attitudes towards learning and how reading is viewed in this universe reveals disturbing patterns.

We have an aspect of creativity and innovation in Singapore but these seem reserved for business and practical things. We place national primacy on Stem (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and fixate on jobs that pay the most.

Even when we educate children, we focus their minds on functional reading – on mastering textbooks that are the subject of exams, on comprehending concepts in assessment books and even for fiction, to check off classical texts on required reading lists.

What cultural currency children gain today is less from stories and tales of the written word, and more from Disney cartoons viewed passively, which begins as YouTube videos screened during mealtimes to get restless toddlers to sit and eat.

Our lazy reading patterns as adults betray our thinking that reading is hardly the national pastime. More people are reading, according to the National Reading Habits Study by the NLB, but only a third

To address both forces, we must find a way to model a love for learning and develop a genuine love for reading. It should not be a chore or a task awaiting completion.

After all, curiosity, creativity and empathy honed by avid reading are traits valued in today’s uncertain world. A sense of play, experimentation and adventure can lift the spirits of our children and help them to grow into better people. Books do this best.

Award-winning British author Katherine Rundell said in her prize-winning book Rooftoppers: “Books crowbar the world open for you.” Fiction exposes children to new worlds. These books provide readers a sense of confidence and give shape to the continuous flux in the world around them. They can endow us with courage to face complex issues in the same way our story heroes and heroines slay dragons and overcome adversity.

In these modern times of artificial intelligence (AI) and robots, we must nurture people’s creativity through expanding their inner consciousness. However brilliant AI is, it will never have the emotional consciousness and emotional quotient of a warm, living, breathing person.

Reading should be done preferably with a physical book rather than an iPad. Holding an inviting sheaf of paper injects one with the energy of life and focuses the mind in ways an e-book as a medium encouraging passive viewership cannot provide.

Start them young

Internet entertainment, video games and social media have grown in popularity since they exploded on the scene two decades ago and will continue to compete for people’s leisure time.

But people with a modicum of intuition will soon reach a point where facile entertainment becomes repetitive and boring. Though some of the most thoughtful high-quality video games and the power of gaming to improve writing can build literacy and get young gamers to engage with stories, adult curation will still be key to selecting suitable games.

But there is nothing like a book that draws the reader into whole new worlds, not just by the power of the writer’s pen, but by also requiring the reader to exercise his imaginative prowess. Good writers take you on an exploratory trip and present you with sparkling new ideas. The reader interacts and engages with the book at various levels, intellectually and emotionally.

The book must continue to live because people hunger for something great, for an experience beyond the mundane. A book is more than printed words on paper; it’s a vehicle for expansion and change. A book is a rabbit-hole where readers can escape to a fantastical world where anything can happen.

And if we want our children to develop that love of learning and reading, we best pick that up ourselves.

Josephine Chia has published 14 books. Her latest novel is Emman Time Traveller, The Redhill Tragedy. Her book Kampong Spirit Gotong Royong won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2014.