On The Ground

PAP conference: Urgent social and political challenges have to be tackled

The messaging that it cannot be business as usual comes amid societal and political changes.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The speeches by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong acknowledged that more fundamental policy changes are needed.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

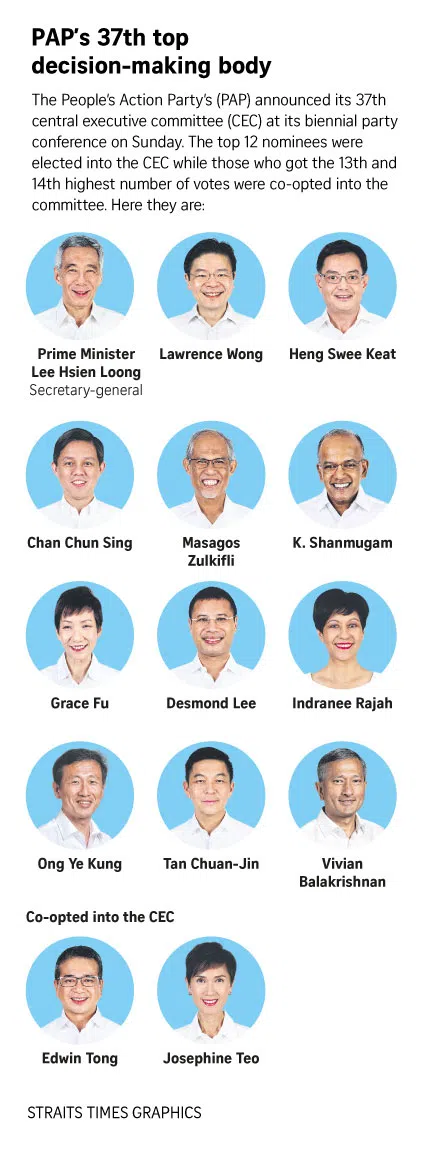

On Sunday, as they’ve done every two years since 1982, more than 3,000 men and women in white gathered for the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) conference where they elected the party’s top decision-making body.

The election was significant because the Central Executive Committee (CEC) is the party’s nerve centre: It screens election candidates at the final stage, and makes pre-election decisions on which MPs will be retired. Historically, it also decided on the setting-up of party bodies such as the HQ Executive Committee, the PAP Community Foundation, Women’s Wing and Youth Wing.

Each PAP conference has two notable parts: the CEC elections, and leaders’ speeches.

The elections

The PAP, formed in 1954 and in power since 1959, has had cadres since the 1950s. One way it saw to stop communist infiltration was by confining the power to elect party leaders to this smaller inner circle.

In her 1971 thesis Singapore’s People’s Action Party: Its History, Organisation and Leadership, former diplomat Pang Cheng Lian colourfully described CEC voting as a closed system, in which “the cardinals appoint the pope and the pope appoints the cardinals”.

Per Article VII of the party’s Constitution, 12 places are filled formally by the election process, while no more than six members may be co-opted into the CEC. The 13th and 14th highest scoring candidates are usually co-opted into the CEC at the party conference itself.

There were times when individuals who weren’t on the nomination list at the party conference were later co-opted by the CEC. This enables younger MPs and ministers who may not have their own support base within the rank and file of party cadres, but who the CEC feels are part of the core leadership or who represent younger MPs, to be brought in. An example was the co-opting in 2018 of fourth-generation (4G) leaders such as Lawrence Wong and Desmond Lee.

This year, other than the chairman of the 35th and 36th CECs, Minister for Trade and Industry Gan Kim Yong, not standing for re-election to the committee, the composition of the CEC did not change significantly. Minister for Culture, Community and Youth Edwin Tong and Minister for Communications and Information Josephine Teo were co-opted into the CEC as they received the 13th and 14th highest votes.

This is in keeping with what PM Lee Hsien Loong pointed out on Sunday, which is that the 4G had earlier chosen Mr Wong to lead them

Moreover, the bulk of the transition from 3G to 4G already took place in 2018. That year saw the retirements of Messrs Khaw Boon Wan, Yaacob Ibrahim, Teo Chee Hean, Tharman Shanmugaratnam and Lim Swee Say as CEC office holders.

Further co-options, and decisions on filling the CEC office-bearing positions, are decided subsequently at the first CEC meeting shortly after the conference. Office-bearing positions include the chairman, vice-chairman, secretary-general, assistant secretary-general, treasurer, assistant treasurer, and any other posts the CEC sees necessary to establish.

One development to look out for next could be the election of Mr Wong as the first assistant secretary-general, or ASG. Under the PAP Constitution, the ASG “shall assist the secretary-general in the discharge of his duties, powers and responsibilities and in the absence of the secretary-general shall act in his place”.

The post has traditionally been held by the prime minister-in-waiting, such as Messrs Goh Chok Tong, Lee Hsien Loong and Heng Swee Keat previously, or by a deputy PM or DPM-to-be.

The speeches

Each conference speech is broadly similar: There is an overview of the global political and economic situation, their impact on, as well as political and other developments within, Singapore, and a call to action.

In 2016, PM Lee, who is party secretary-general, warned of sharpening divisions His 2020 speech

So, by most measures, the speeches by PM Lee and Mr Wong on Sunday were no different. Global situation? Check. Both men opened their speeches against the backdrop of US-China tensions. Representing all Singaporeans and winning their trust and confidence? Check.

But there was a palpable sense of social and political urgency.

Societal changes

For one thing, Singapore society has changed and is changing: From the size of families and ageing profile of its population, to disparate salaries of different groups of workers, Singapore’s ethnic and nationality make-up, and the huge accumulation and inflows of wealth and capital.

As Nanyang Technological University Associate Professor Teo You Yenn said in a speech at the Singapore Economic Policy Forum

Hence, Sunday’s speeches acknowledged that more fundamental policy changes are needed. Mr Wong, for example, signalled moves under the Forward Singapore engagement exercise

But governing well also entails doing well in politics. On this, the messaging was sharper than in previous years.

In his 2020 speech, PM Lee delivered this line: “You must have guts, you must have conviction, you must have that spunk and that fight… believe in it. Stand for it. Fight for it. If need be, die for it.”

While there was no talk of dying this year, there was still talk of fighting. More importantly, PM Lee discussed at great length that Singaporeans can’t have it both ways

Watching the vote share

There are two reasons for this. The first is internal: Had the PAP won GE2020 narrowly with a 51 per cent vote share instead of 61.2 per cent, it would have lost many good MPs and ministers. It would have been much harder for the Government to act decisively, including during crises such as Covid-19.

The second is external: A Singapore ruled by a government hanging on to power by its fingernails is bound to be pushed from pillar to post by other countries. PM Lee said: “At the very least, everyone will say: ‘Hang on, stand back. Watch and see. Will they still be there tomorrow?’”

Mr Wong pointed out that the sum of the votes the Workers’ Party (WP) received across its six contests in the 2020 election was slightly more than votes for the PAP.

These numbers were publicly available right after the elections: The WP secured just over 50 per cent of the total vote in the four group representation constituencies and two single-member constituencies it contested in against the PAP. But Sunday was the first time the party explicitly made it clear how, in the constituencies where there was a straight fight between both sides, more people had collectively voted for the WP than the PAP.

Extrapolating this to the rest of the country and to future elections, the real risk is that if the WP contests more seats, the PAP may not win the majority of votes nationwide, or even be returned to power. Nor is it inevitable that Mr Wong will become PM.

Some may interpret PM Lee’s and Mr Wong’s “fighting” speeches as a huge hint that Singapore will head into a general election next year, which also happens to be when the presidential election will be held.

But I’m not so sure. I don’t think the perceived temperature of a speech is a reliable indication of when an election will be held. Plus, holding a presidential election and general election in the same year, such as in 2011, is the exception to the norm.

Rather, I believe the speeches were an impassioned repudiation of the belief that has taken hold among some Singaporeans – and which has been reinforced by messaging from the opposition – that the PAP won’t lose its supermajority in Parliament, and that even if it does, it can still carry out its agenda effectively.

WP chief Pritam Singh, for example, had said during a GE2020 walkabout

The risks

The talk of political challenges isn’t just aimed at the public who aren’t all convinced, but also at the party’s own ranks: That it needs to step up to counter the opposition and not give it a free pass.

Part of this comes down to inexperience, something that live Parliament debates

But the larger problem is that even if one can argue well, threading that needle has just become much more difficult in an era of short attention spans and quick tempers.

What’s the worst that can happen to a politician who mangles facts and figures? He gets admonished, and every minute of admonishment detracts from constructive debate. The person who admonishes him, even if correctly, appears to the public like a bully.

It is hard for even an engaged citizen to visualise a crisis that wasn’t. This is what happens when your best and most important work is largely invisible, the Financial Times’ Janan Ganesh wrote evocatively in July.

“Unable to see that less responsible leadership would have led to mass suffering, we feel at liberty to take risks in the polling booth. And so the absence of disaster becomes its own kind of disaster,” he said.

Last year, when I interviewed political historian Shashi Jayakumar

Dr Jayakumar noted that the party leadership, in its GE2020 post-mortem, had not come to a fatalistic appraisal concerning the irreversible tide of PAP decline. Nor do most PAP leaders think that a two-party system featuring a strong opposition is inevitable.

But the possibility of that happening grows with time; for the PAP, it cannot be business as usual. The outcome is existential for both the country and the party. The stakes will get higher with each successive election as the PAP keeps getting returned to power – until it doesn’t.