Modi and the art of geopolitical flattery

Behind the charm offensive by Biden and Albanese lie hard-headed calculations.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

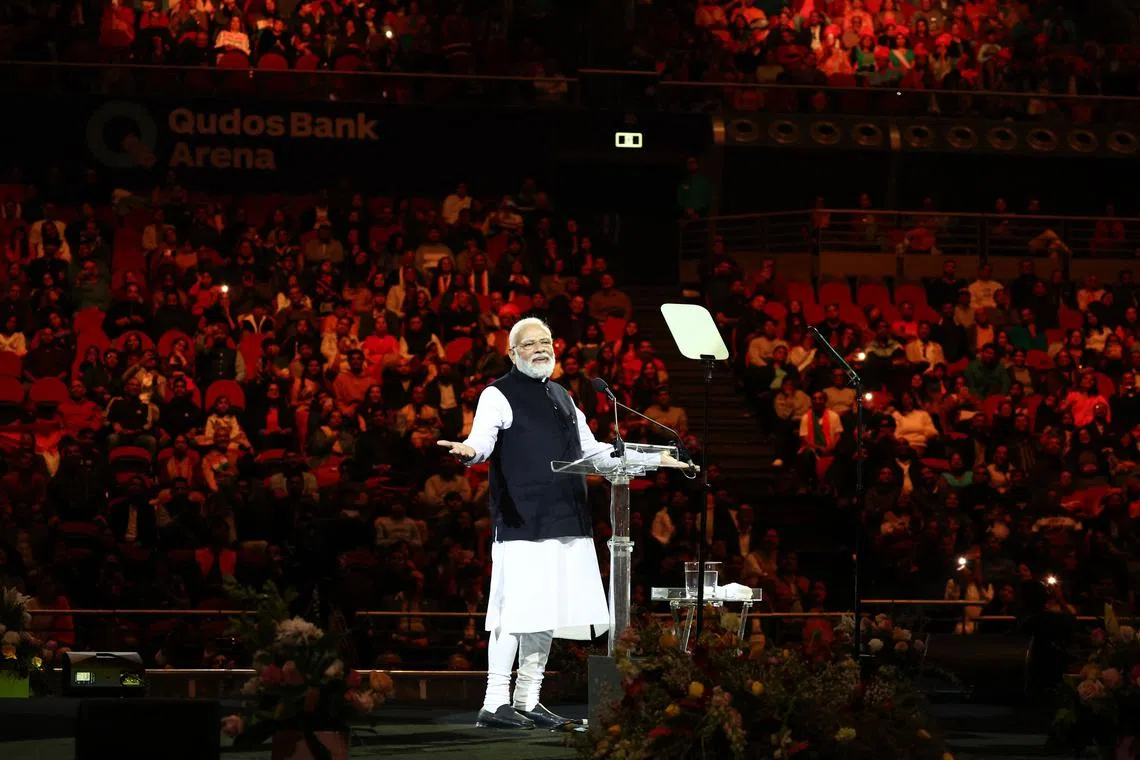

Indian PM Narendra Modi (left) and Australian PM Anthony Albanese during an event at Qudos Bank Arena in Sydney, on May 23, 2023.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

When the President of the United States lavishes praise on your many accomplishments and says perhaps he should get your autograph given your immense popularity, it is difficult to not be pleased.

“You are causing me a real problem,” President Joe Biden was quoted as saying to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a Quad meeting in Hiroshima in May. “Next month we have a dinner for you in Washington. Everyone in the whole country wants to come. I have run out of tickets... I am getting phone calls from people I have never heard of before. Everyone from movie stars to relatives. You are too popular.”

Days later, more fulsome praise followed, this time from Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who called Mr Modi “The Boss”, referencing the nickname of rock star Bruce Springsteen. But there’s more – the American singer-songwriter has apparently been eclipsed by India’s prime minister. “The last time I saw someone on this stage was Bruce Springsteen, and he did not get the welcome that Prime Minister Modi has got,” Mr Albanese said, as thousands gathered at Sydney’s Qudos Bank Arena cheered.

It’s hard to imagine Mr Modi being unaffected by it all. The conversation between Mr Biden and Mr Modi took place in a semi-private setting on the sidelines of the Group of Seven summit in Hiroshima.

The other, with Mr Albanese, was at a public event where the Indian diaspora had gathered to fete the visiting Mr Modi.

The one-two soft-soaping by Messrs Biden and Albanese of the 72-year-old Mr Modi is a calculated play to the ego of the Indian leader, still smarting from his Bharatiya Janata Party’s electoral drubbing in Karnataka – the only southern Indian province it controlled – despite vigorous campaigning by the prime minister himself.

It is a big turn from a few months ago when the US focused on a serious sit-down between Mr Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Group of 20 summit in Bali, in order to set guard rails on their deteriorating relationship. Mr Modi had barely managed a handshake with Mr Biden then.

The calculations

What’s changed? Since the Xi-Biden meeting, the Sino-US relationship has barely improved. In some areas, the relationship has deteriorated, as seen in the escalating semiconductor curbs from both sides. Then came news from the Pentagon that the Chinese had rebuffed a US proposal for talks Chinese air force flew a fighter dangerously close

So now, the US, which had become frustrated with India’s tardiness in pulling its weight on the security dimensions of the Quad, seems to have discovered reasons to renew its enthusiasm for a heightened wooing of the South Asian giant.

While some think it is a feint to prod a watchful China to start negotiations with it, or a decision to play the long game with India never mind its irritatingly close ties with Russia and refusal to condemn Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine,

Mr Austin is set to fly to New Delhi from Singapore to put the finishing touches to the defence part of significant agreements to be signed during Mr Modi’s oddly titled “official state visit” to Washington later this month, which culminates with a June 22 White House state dinner.

It is only the third in the Biden presidency, after earlier ones for French President Emmanuel Macron and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol. And it was in the context of the clamour to secure invitations to that feast that Mr Biden had enthused about Mr Modi’s popularity.

More of that wooing, and where it ultimately leads, will come clear in the coming weeks, and South-east Asia, particularly, will watch with deep interest.

Indian PM Narendra Modi during an event with members of the local Indian community at the Qudos Arena in Sydney on May 23, 2023.

PHOTO: AFP

India’s refusal to sign on security systems seen to target another nation and particularly China – dubbed “fence sitting” in the West – has so far provided a measure of ideological cover for other Asian nations that are threatened with similar dilemmas.

Any dilution of the Indian position therefore will reverberate across the Asia-Pacific and coincide with a moment when some of Asean’s biggest nations, starting with Indonesia and the Philippines, have noticeably warmed to Aukus, the security arrangement tying Australia with Britain and the United States, as well as the four-nation Quad.

While military alliances are still some distance away, strategic coordination is swiftly gaining pace.

Pushed by the US and Japan – Prime Minister Fumio Kishida travelled to New Delhi in March

The Quad extends this tightening relationship with the US to also wrap in America’s closest regional allies, Japan and Australia. The annual Exercise Malabar, which started as a US-India bilateral navy war game off India’s Arabian Sea board, has steadily moved east, and now includes all Quad members. The next iteration of the war game is to be conducted off the coast of Australia in August.

In his opening remarks at the impromptu Quad summit in Hiroshima, Mr Biden said meaningfully, but without expanding, that “people are going to look back at the Quad in 10, 20, 30 years from now and say it changed the dynamic not only of the region, but the world.”

Soon after that meeting, both Mr Modi and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, standing in for Mr Biden who had to return to Washington to deal with the debt crisis, held summits with Pacific Island nations on the same day in Port Moresby.

In September, the two nations will organise a conclave of military chiefs from the 14 Pacific Island nations, moves that suggest that while New Delhi may baulk at participating in something as raw as a crisis in the Taiwan Strait it is ready to operate tightly with the US military at the fringes of the Asia-Pacific.

Japanese PM Fumio Kishida (right) and Indian PM Narendra Modi during their visit at the Buddha Jayanti Park in New Delhi, on March 20, 2023.

PHOTO: AFP

This is why the Modi-Biden summit takes on much meaning. American officials are talking up the event, which looks like it could produce an agreement for technology transfer and localised production in India of front-line General Electric F414 engines for India-made fighter aircraft.

This, and some other agreements to be announced on technology collaboration, they say, could mark a breakthrough similar to the landmark civilian nuclear deal inked in 2005 by then President George W. Bush and then Indian leader, Dr Manmohan Singh.

Tellingly, Mr Modi’s principal secretary was in Washington for several days in late May, fine-tuning the visit – a job usually handled by the Ministry of External Affairs.

That suggests a political dimension – insistence that ticklish issues such as the Modi government’s approach to its minority religious communities not be brought up, perhaps, or guarantees that nothing will be done to derail or affect Mr Modi’s shot at a third term in office.

Earlier this year, India’s national security adviser, who too reports directly to Mr Modi, also spent several days in the US capital.

What India, and Mr Modi, concede in return for all this, bears watching.

Aside from the landmark engine deal, there is talk of renewed Indian interest in Boeing’s F/A-18 Super Hornets for India’s aircraft carrier programme, where the maritime version of the French Rafales is thought to be the front runner. They will supplement and eventually replace the Russian-made MiG-29s that India currently uses on its flat tops. The Hornets are powered by F414 engines. The two sides are also in discussions on cooperating in semiconductor manufacturing.

The White House announcement on the upcoming talks said the summit will strengthen the respective countries’ “shared commitment to a free, open, prosperous, and secure Indo-Pacific”.

Global prestige

Certainly, the optics around the summit are critical to Mr Modi, who is slated to seek a third term in office next year, in national polls widely expected to be held in April-May. Beset by a mounting jobs crisis, inflation and worries about a coalescing opposition, Mr Modi seeks to go before an increasingly restive population by highlighting Indian prestige rising globally.

Earlier this year, India convened the Global South Summit. Soon after this month’s White House state dinner, Mr Modi travels to Paris to be guest of honour at France’s Bastille Day celebration – another high visibility event for the home audience. While India just downgraded the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit it is hosting in July to a virtual meeting, it is making a huge flash of September’s G-20 summit. Mr Modi seeks to showcase India under his watch as nothing less than the “Viswa Guru” – guru to the world.

While China probably has no objection to Mr Modi taking the global limelight, it will be less sanguine if the trade-offs involve seeing a tightening of the US security embrace, or a tilt towards turning the Quad into what it calls an “Asian Nato”.

In recent Track 1.5 discussions, it has conveyed veiled suggestions to India that Mr Xi has the option to not show up when it hosts the twin summits later this year, thereby reducing the importance of the twin events.

New Delhi seems to believe it can live with that. Its bigger fear is that Mr Biden may skip the G-20 summit, a development that would be seen as calamitous for Indian prestige and therefore, it is critical that he be kept onside. By moving the SCO summit to a virtual one, it has made it easier for the Chinese leader to attend both – the G-20 in person.

“Mr Xi would look churlish if he skipped the SCO summit – it is their outfit, after all,” says a person with access to Mr Modi, referring to the fact that the SCO was a Chinese idea. “If he skips G-20, he would need to send someone in his place and watch that person rub shoulders with the likes of Biden, Macron and perhaps Putin –and see if that works for him.”

It does look like this is India’s year on the world stage. Whether the nation will need to make any adjustments to its prized strategic autonomy as payment for all the glory remains to be seen.