Economic Affairs

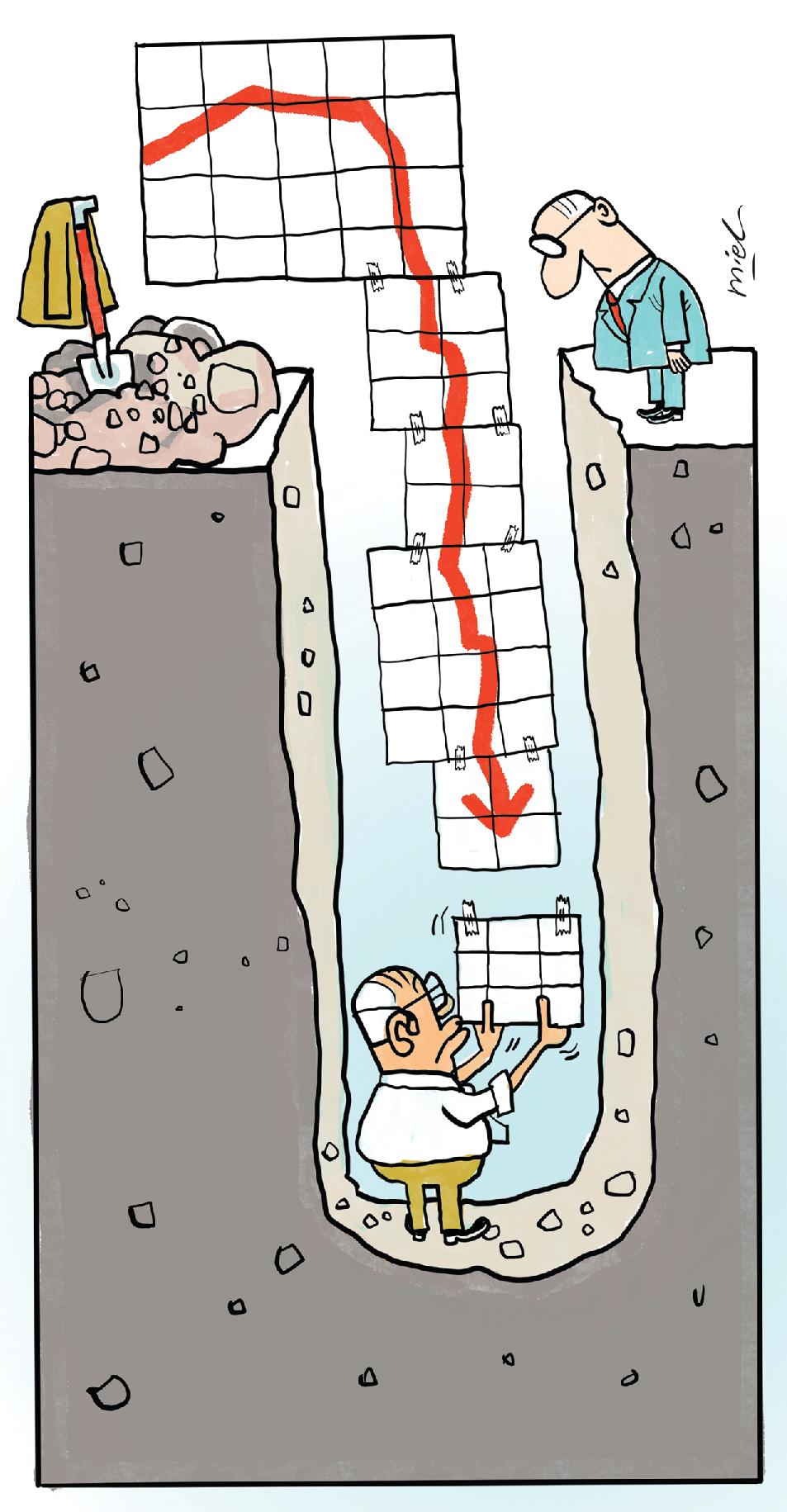

The 'R' word is coming into play: Why recession risks are rising in major economies

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong warned of a possible recession next year or in 2024 in his May Day Rally speech.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

Follow topic:

Over the past few months economists and the public have been riveted by inflation, and understandably so, given that it has hit multi-year highs in many countries. But in recent days, Google Trends has indicated that interest in the word "recession" has been spiking. Geographically, the top source of this interest has been the United States. Singapore comes a close second. In his May Day Rally speech, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong warned of a possible recession next year or in 2024.

Interest in recession has heightened since the US Federal Reserve raised its funds rate by a hefty 50 basis points last Wednesday - the biggest increase since 2000 - and signalled two more hikes of the same size next month and in July. To the relief of financial markets, Fed chairman Jerome Powell indicated that a hike of 75 basis points, favoured by some of his more hawkish colleagues, was not something the Fed's rate-setting committee was "actively considering". So in a knee-jerk response the day the rate increase was announced, stock markets rallied.

Reality dawns

But this proved to be what market watchers call a dead cat bounce. By last Thursday, reality had dawned and all the previous day's gains were erased and more. US markets fell further last Friday, capping the worst weekly losses in a decade. They fell even more on Monday, bringing year-to-date losses to16.3 per cent for the S&P 500 and 25.7 per cent for the technology-heavy Nasdaq.

Sharp declines in stock markets are often (though not always) a bugle call ahead of bad economic times to come. That inflation is high and rising was well known for a while. It didn't seem to greatly perturb markets, which continued to climb last year even as the inflation numbers came in higher and higher. But the reality of the Fed's monetary tightening cycle, which has triggered similar reactions from several other central banks, has given investors the jitters.

That tightening promises to be more aggressive than anything we have seen before. Three successive hikes of 50 basis points - accompanied by what may be four smaller hikes in one year - is rare enough. On top of that, the Fed will be shrinking its US$9 trillion (S$12.5 trillion) balance sheet, starting next month, meaning that it will stop reinvesting the proceeds of maturing Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, which will drain liquidity from financial markets.

The last time it did this in 2017 was about two years after it started raising rates. This time, there will be a lag of only three months. This double whammy is the equivalent of the Fed not only yanking the punchbowl from the party but, for good measure, coming back to spray cold water on the partygoers.

If stock markets continue to tank, which experts suggest is highly probable, this will lead to the usual snowballing effects that take hold during bear markets - margin calls on leveraged investors, forced sales of holdings even of blue-chip stocks, leading to still more sell-offs and serious erosions of company valuations and household wealth.

But this is not just a story about the financial markets. More importantly, it is a story of what is going on in the real economy.

Solving for inflation

We know that inflation has been rising, driven by soaring food and fuel prices, aggravated by Russia's war on Ukraine as well as the draconian lockdowns in China that have fractured already fragile supply chains and raised shipping costs. So the Fed's focus is to solve for inflation. As of now, everything else, including the real economy and the fate of financial markets, is a secondary concern.

In his testimony and press conference last Wednesday, Mr Powell acknowledged that a lot of inflation is supply-side driven, arising from food and fuel prices as well as supply chain snarls, and that there is not much the Fed can do about those problems. "But there's a job to do on demand," he said.

He emphasised that the US labour market is tight, with unemployment at a low 3.6 per cent and 1.9 vacancies for every unemployed worker. Through some demand destruction via restrictive monetary policy, the Fed hopes to bring the labour market back into balance, which would prevent a wage-price spiral.

He admitted there would be some pain associated with this - which would most likely include more unemployment and tanking asset prices - but the bigger pain, he suggested, would come from not dealing with inflation and allowing it to become entrenched.

If all goes according to plan, the Fed would be able to pull off what Mr Powell called "a soft, or softish landing". He admitted that the job would not be easy, and history bears this out. Of the last 14 rate-hiking cycles, 11 ended in a recession. It is also notable that historically, recessions have faithfully followed sharp spikes in food and fuel prices, as in 1973 to 1975, 1981 to 1983, 1990 to 1991 and 2007 to 2008.

Tightening into weakness

The Fed's job will be even more difficult for the fact that it will be tightening into an economy that, although not in recession, is weakening. In a flashing warning sign, US gross domestic product (GDP) growth surprisingly shrank 1.4 per cent on an annualised basis in the first quarter of this year, the first slowdown since April 2020, and there is no fiscal stimulus to come to the rescue this time. Although last month's job report was healthy, with 428,000 jobs created, that is a lagging indicator.

The latest forward-looking indicators are trending down, not up. For instance, the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) index has been dropping since last November, although it is still in positive territory (pointing to expansion, but at the slowest rate in five months). The employment component of ISM has also been falling and is only barely positive at 50.9 (any reading below 50 indicates a contraction), pointing to a possible slowdown in employment growth ahead.

In another ominous sign of weakness, the US housing market is slowing after sharp increases in mortgage rates during the past three months as long-term Treasury yields rose. As it ripples through the economy over the next few months, the housing slowdown will have an impact on other industries such as construction, durable goods, furniture and appliances.

On top of all this there will be a negative wealth effect arising from sharp declines in equity prices, which will lead to trillions of dollars in wealth destruction that in turn will cut into consumer spending - the main engine of the US economy.

Headwinds in Europe and China

Besides the US, other major economies are also facing serious headwinds, which raises the risk that they will all be slowing at the same time. The euro zone's growth is anaemic, with quarter-on-quarter expansion at just 0.2 per cent for the January to March period. A planned oil embargo on Russia and an escalation of the war in Ukraine could tip it into recession.

In China, multiple cities that together account for an estimated 40 per cent of GDP are under full or partial lockdown. China's official growth target of 5.5 per cent looks out of reach. Most economists have downgraded their growth projections for China to between 4 per cent and 5 per cent, and even those estimates may be further cut if the country's zero-Covid-19 policy persists. China's export growth has already slumped to 3.9 per cent last month, the lowest since June 2020, compared with 14.7 per cent in March.

China's slowdown will especially affect Asian economies, which are closely linked to China's. Their exports to China will flatline or decline and they will get less investment in infrastructure under China's Belt and Road Initiative as Beijing expands its own infrastructure investments in response to its slowdown.

Asian countries, together with other emerging economies, are also vulnerable not only to high food and fuel prices - most of these nations are net importers of both - but also to the sharp rise in the US dollar. The US dollar index, which measures it against a basket of six major currencies, is close to a 20-year high. The credit rating agency Fitch estimates that emerging economies' median foreign-currency government debt increased to 31 per cent of GDP at the end of last year, from 18 per cent in 2013.

A stronger US dollar, coupled with rising US interest rates, will make it more expensive for governments of these economies to service their dollar debts. They may also be forced to raise interest rates to prevent capital flight and depreciations of their currencies, which would add even more inflationary pressures to what they already face. Higher interest rates will, in turn, slow their growth.

Worst hit will be the governments of low-income countries. Last month the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that 60 per cent of these countries were either already experiencing debt distress or were at high risk of it, compared with 30 per cent in 2015.

There are also private debts. According to the Bank for International Settlements, at the end of last year, the outstanding US dollar debts of non-financial corporations of developing countries in the Asia-Pacific was US$909.4 billion, of which US$139.3 billion was due within one year. A lot of indebted companies in Asia will be financially stressed by a strong US dollar and higher US interest rates.

A global recession is not certain, but PM Lee is right to flag it as a risk to watch.

Indeed, increasing numbers of economists are now making it their base case. For instance, Professor Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University, who is also the former chief economist at the IMF, has warned of recession risks not only in the US but also in Europe and China, "possibly all reinforcing each other like the perfect storm". In its financial stability report on Monday, the Fed acknowledged that sharp increases in interest rates will pose risks to the US economy and "could negatively affect the financial system".

It may not be long before these risks loom larger on the Fed's radar screen, in which case, there is a chance that it may pause or even roll back its rate-hiking cycle. This is a story that could yet have many twists and turns.