China protests – the wake-up call paving the way for better Covid-19 control measures

Poor command and control partly to blame for confusion on the ground that’s throttling the economy, but push to vaccinate the elderly suggests early sign of change.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Though there is officially no exit from China's zero-Covid-19 policy, recently introduced guidelines offer more flexibility.

PHOTO: REUTERS

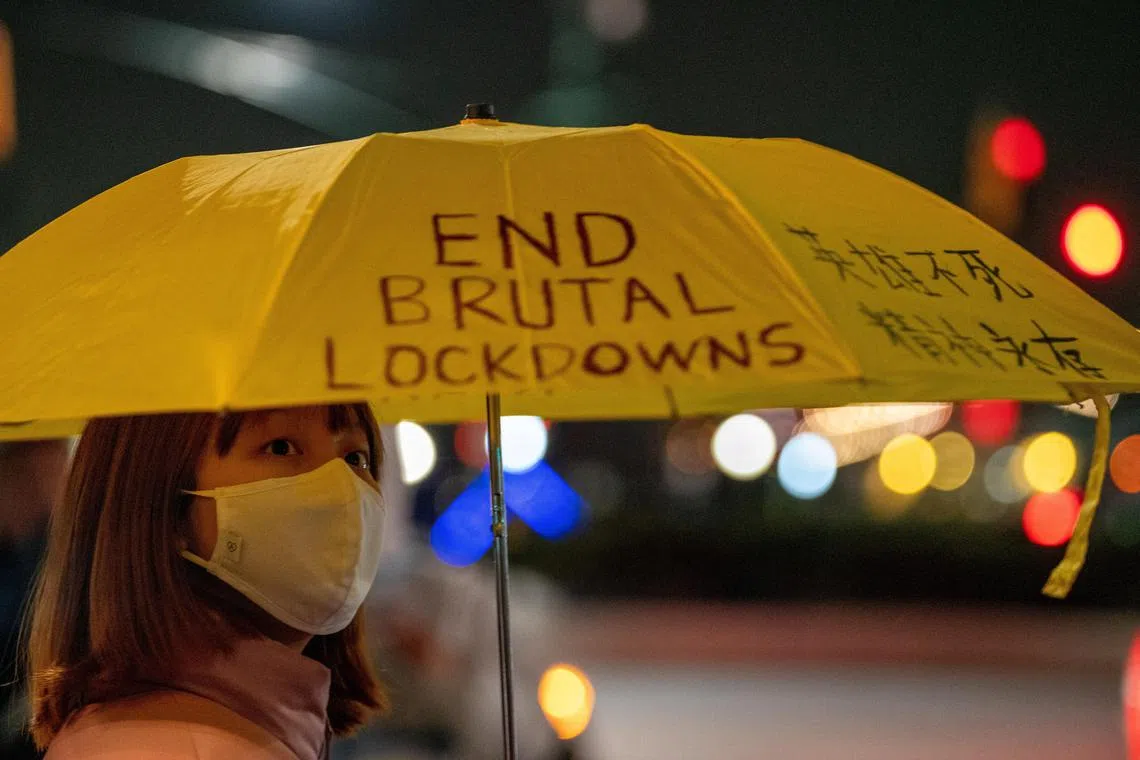

Frustration over China’s zero-Covid-19 policies finally boiled over last week in a rash of protests across the country.

Defusing China’s Covid-19 crisis will take time and won’t be easy. But the country has considerable state capacity at marshalling resources, which should help if properly directed. What it needs now is political acumen to reverse unsustainable policies, a greater sense of urgency and less chaotic implementation of its pandemic directives.

The outbreak of protests, reported in more than a dozen cities, is notable for being the first nationwide protest in decades, and for drawing a wide spectrum of ordinary citizens – from university students to small business owners. Protests flared up earlier in the form of a huge social media backlash following the deaths in September of dozens of bus passengers in Guizhou province while on their way to a quarantine facility. The violent workers’ revolt at the Foxconn factory in Zhengzhou in October was also partly sparked by Covid-19 measures.

Though there is officially no exit from the zero-Covid-19 policy,

However, the decentralised implementation of the plan, necessary as it is in a country the size of China, resulted in much chaos and confusion as well as many about-turns in cities that saw a rapid rise of their infection numbers – even though casualties remained very limited.

Who’s to blame?

On Tuesday, at a first press conference after the protests, officials of the State Council task force in charge of Covid-19 measures accused local officials of reckless and excessive measures in implementing lockdowns, heedless of public concerns. Beijing still insists it won’t budge from the present zero-Covid-19 policy, but clearly the central government is shifting blame for the unrest elsewhere.

Policy communication from the top, though, may also have been wanting. In the “interregnum” between the 20th Party Congress and the National People’s Congress next March, there is a bit of a power vacuum. Leaders such as Premier Li Keqiang and Vice-Premier Sun Chunlan – who has played a prominent role in Covid-19 policies, including the lockdown of Shanghai – are no longer part of the new Politburo. Ms Sun has been less visibly leading the new policy directions, thus leaving local officials in limbo on how to implement them.

What can China do better if shifting towards a “living with Covid-19” policy is still a bridge too far?

First, significant changes are feasible based on the guidance in the 20-point plan.

Vaccinating the elderly, who are most prone to severe Covid-19 and death, is particularly important, but the number of fully vaccinated elderly people over 60 years old has been stuck at around 67 per cent for months – too low for the country to safely open up. The State Council task force announcement on Tuesday of plans to ramp up vaccination of the elderly

A second measure is to reconsider the policy of isolating Covid-19 cases in special facilities. Countries such as Singapore phased out such isolation early on as home quarantine was seen to be as effective, much less disruptive for the individual, and far less of a burden for the health system.

Testing times

A third is a shift of resources away from testing and containment towards vaccination and support for those in home isolation. Performative policies such as testing fish and clams in markets and walling off buildings and streets have no scientific basis, and the people engaged in these processes can be much better employed elsewhere.

Although leading epidemiologist Liang Wannian has said that China has sufficient capacity to test one billion people a day, the bigger question is whether that money is well spent and whether it can be sustained.

According to one estimate by Dongwu Securities, the mass testing campaign could cost up to 1.7 trillion yuan (S$327 billion) a year, or about 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). Meanwhile, local governments are struggling to pay their bills for all the tests and quarantine facilities. Hospitals are also under growing strain as healthcare staff and other resources are diverted to mass testing and quarantine.

The broader economy is also suffering as the lockdowns continue. Cities accounting for 70 per cent of GDP now have areas that are classified as high or medium risk, according to HSBC, an investment bank. Nomura, another bank, estimates that areas with at least partial lockdowns and travel restrictions account for more than 25 per cent of China’s GDP, as reported by the Financial Times.

To be sure, not all sectors are ailing. Andon Health, a Shenzhen-listed medical devices company, reportedly enjoyed a 32,000 per cent jump in net profits in the third quarter of 2022, compared with the same period in 2021, thanks to churning out Covid-19 tests for the domestic and export markets.

The economic casualties

But generally, China’s commitment to zero-Covid-19 has become far more expensive in economic terms. The new variants require more frequent lockdowns, which is a big blow to the services sector – a sector that, far more than manufacturing, requires people to meet face to face.

The labour-intensive services sector, in particular, has been hurting. This includes many mom-and-pop shops and restaurants that provide jobs for low-wage migrants as well as high-value property, finance and consumer technology sectors, and these are the sectors that previously generated the jobs for China’s rapidly rising number of university graduates.

A health worker wipes the door to a fever clinic at a hospital as Covid-19 outbreaks continue in Beijing.

PHOTO: REUTERS

The class of 2022 graduates into a very different economy, with growth to reach barely 3 per cent in 2022, according to the International Monetary Fund, compared with 6 per cent to 7 per cent in the years before Covid-19.

It is therefore no surprise that the young are particularly frustrated, as they are worst-hit by the impact of Covid-19 measures on the economy. Youth unemployment peaked at almost 20 per cent some months ago, and major companies, in particular consumer tech companies and those in e-commerce, are not hiring after the regulatory crackdown of recent years.

Reviving economic growth will require more consumption. China’s recovery after the first wave of Covid-19 relied disproportionately on exports of manufactured goods and on infrastructure. Now, the world economy is cooling and local governments are weary of investing more, as the property downturn is squeezing their revenues. Encouraging domestic consumption will require further steps to relax China’s Covid-19 policies, which should pay off in a recovery of consumer confidence, currently at rock-bottom levels.

There is little doubt that China’s security apparatus can manage the current level of protests, and thus far the authorities have shown restraint. Still, controlling the unrest will not take away the frustration or revamp economic growth. Instead, the protests could nudge the authorities towards better Covid-19 policies in the coming months.

Bert Hofman is director of the East Asian Institute and Professor in Practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.