CDC vouchers do more than help people cope with rising prices

The scheme complements existing forms of support for citizens amid rising prices.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Despite a softening economy, high inflation looks set to persist in 2023.

PHOTO: ST FILE

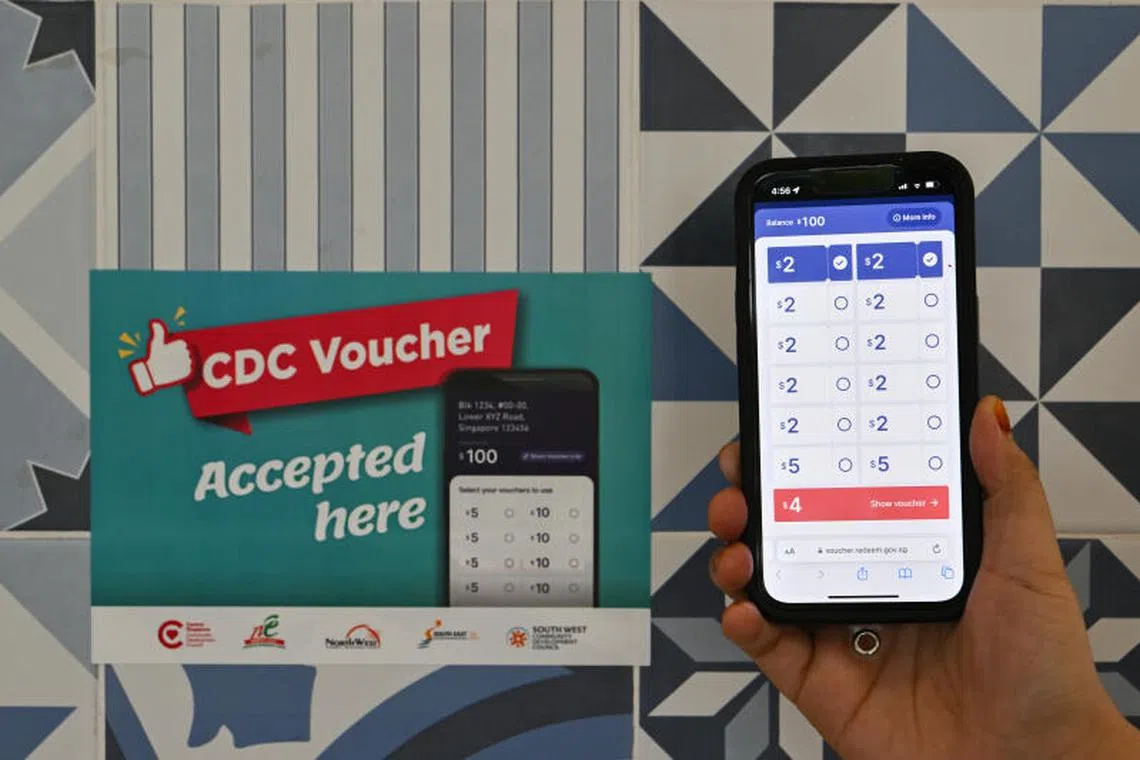

Last Tuesday saw more than 300,000 households – nearly a quarter of those eligible – claim the latest tranche of Community Development Council (CDC) vouchers on the first day of their release.

Of the $300 in vouchers

This brings the total value of CDC vouchers disbursed by the Government

This amount may seem modest to some, but should be viewed in the context of broader efforts to help all Singaporeans, particularly the less well-off, to cope with rising prices.

Despite a softening economy, high inflation looks set to persist in 2023. The Monetary Authority of Singapore expects headline inflation this year to be between 5.5 per cent and 6.5 per cent,

While Singapore’s expected inflation rate of 6 per cent in 2022 would be the highest since 2008, growth in consumer prices has at least been lower than those of advanced countries such as the United States (around 8 per cent), Britain (more than 9 per cent) and the global figure of 8.9 per cent, as per Euromonitor International’s December forecasts.

Still, questions have been raised about the amount disbursed through CDC vouchers and whether the vouchers ought to be given to affluent households. Can the Government afford to give more? And are vouchers the best way of helping citizens with the rising cost of living?

Targeted support necessary, but don’t begrudge broad-based help

Optimising fiscal resources requires that social support be targeted at those less well-off. Structural support in the form of the Workfare Income Supplement (WIS)

In addition to these automatic disbursements, there remains a need for targeted support for a smaller group of vulnerable Singaporeans through the Community Care (ComCare) schemes, along with accompanying social services.

The Assurance Package

This reflects an approach to social transfers that has become particularly salient in recent years: Everyone receives something, but the less well-off receive more. This helps to engender inclusivity while ensuring that the bulk of support goes towards those who need it most. The CDC vouchers, along with the baseline cash payout under the Assurance Package, are the component of support everyone receives.

Those who do not need the vouchers may donate them to charity, and should be encouraged to do so. This fosters a spirit of community giving, where the better-off lend a helping hand to fellow citizens rather than rely solely on the state to redistribute resources.

The eclectic mix of support channels may appear messy, particularly when eligibility criteria differ across schemes, but there are reasons for this. A uniform income criterion applied across all support types risks creating a cliff effect whereby support falls off beyond a single income threshold, which may lead to perverse incentives and outcomes, including disincentivising people from earning higher incomes.

Some of the support mechanisms also have supplementary aims. While cash provides the recipient the greatest flexibility, CDC vouchers have the further aim of supporting heartland merchants and stallholders. This is why of the $300 in CDC vouchers disbursed to each household in January, half remains ring-fenced for spending at heartland shops and hawker stalls.

Ad hoc payouts provide flexibility but are not a long-term fix

Whereas the Government has in years past often shared Budget surpluses with citizens, recent support since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic has taken on a different texture. The former reflects a desire to share the fruits of progress, while the latter is needs-driven, arising from the economic fallout of the pandemic, and now, high inflation.

Ad hoc payouts provide the Government flexibility to respond to contingencies and tailor support according to its fiscal space. However, they may risk feeding public expectation that such support will be forthcoming whenever there are economic headwinds. The lower-income also require assurance in the form of structural transfers and subsidies, which Singapore has been building up over the years.

The only sustainable way to address high living costs is to ensure Singaporeans have access to good jobs with decent wages. Keeping the economy competitive and dynamic is a prerequisite. So too are labour market interventions to help lower-income workers narrow the wage gap with the median.

The Progressive Wage Model

Higher income and savings growth will reduce the need for downstream transfers in the form of the WIS and Silver Support. However, it is important to remember that not all citizens are able to work or take up full-time employment, whether due to health, disability or caregiving responsibilities.

Hence, there will always be a need for ComCare and other forms of targeted support. More could also be done to support caregivers, particularly in view of the ageing population.

Besides raising incomes and providing social support, there is also a need to improve affordability and enhance purchasing power, which benefit all consumers. These include measures to make food, housing and healthcare more affordable, such as building more hawker centres, ensuring an adequate supply of housing and reforming healthcare insurance.

While Singapore is a price-taker for global commodities and will be an expensive city as long as it remains open to global talent and capital, there is much that can be done to prevent costs from spiking due to domestic bottlenecks or supply crunches.

The Assurance Package gives every adult citizen a cash payout ranging from $700 to $1,600, depending on income and housing type.

ST PHOTO: JASON QUAH

Policy evaluation and experimentation can help optimise support

As fiscal space is limited, it is worth making a careful assessment of the efficacy of Singapore’s portfolio of social support in two key dimensions.

The first is the overall incidence of support on different household types and individuals, given the need to target support at the more needy and vulnerable. It is important to ensure that people do not fall through the cracks.

For instance, a family’s income may cross the eligibility threshold for a particular scheme, but special consideration may be needed due to family circumstances such as long-term illness affecting one or more household members.

As eligibility criteria cannot capture all circumstances without becoming exceedingly complex, there must be sufficient room for public officers to exercise flexibility and discretion in disbursing assistance.

The second is about how support is perceived by the beneficiaries themselves – whether cash payouts, CDC vouchers or utilities rebates – in terms of providing them assurance and meeting their needs. This cannot be left to the imagination of policy designers, but could be informed by focus group discussions and well-designed surveys of citizens of different ages and family circumstances.

The psychological impact on recipients could be factored in along with other considerations in the design of support schemes. Policy experimentation and innovation could also yield novel and potentially more impactful ways of providing support within a given budget, much in the way CDC vouchers have emerged as a new form of support.

It is no easy task to give citizens a greater sense of assurance in a competitive society with a high cost of living, but it is one on which Singapore’s social compact and future prospects depend.

Terence Ho is associate professor in practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. He is the author of Refreshing The Singapore System: Recalibrating Socio-Economic Policy For The 21st Century (World Scientific, 2021).