Can the Singapore story help us through this turbulent world?

The values that formed the bedrock of our past will remain critical for an uncertain future.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Perhaps President Tharman Shanmugaratnam’s landslide win at the recent presidential election, is a testament of how our nation has matured.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Follow topic:

In his book The Ukrainians – Unexpected Nation, Professor Andrew Wilson describes several “way-out” theories for the origin of Ukraine.

Many of them draw on biblical texts, like this one which claims that the Ukrainians were descended from Japheth – one of the sons of Noah – whose descendants went on to found the city now known as Kyiv.

As fantastical as these theories might be, some of them have been endorsed by politicians, including Ukraine’s former president Leonid Kravchuk.

These myths allude to the “ancient origin” of the Ukrainians, a theme that has become a central feature of Ukrainian nationalism, notes Prof Wilson, a Ukrainian studies expert at University College London.

Ukraine is a world away from Singapore but the example illustrates an important point – nations are built on stories like these.

They foster empathy, build solidarity among different groups of people, and bind them to the land they live on. “‘Who we are’ depends crucially on ‘where we came from’,” Prof Wilson writes.

Unlike Ukraine, our stories do not reach back into antiquity.

Singaporeans are familiar with the country’s national narratives of resilience and survival against the odds. It is the mudflats to metropolis story – the tale of an improbable nation that went from Third World to First World by dint of will of its leaders and the hard work of its people.

For decades, these stories were cornerstones of Singapore’s national identity and brought Singaporeans together. But as the global environment sees increasing polarisation and political division, the question is whether such stories still resonate with Singaporeans.

National identity

A big part of the narrative of Singapore’s formative years is the nation’s founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and the role he and his colleagues played in bringing a fledgling nation of immigrants together.

Mr Lee’s vision for Singapore changed the lives of millions of Singaporeans, who otherwise might have been born in an economic backwater in South-east Asia.

Last week, as Singapore marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of Mr Lee,

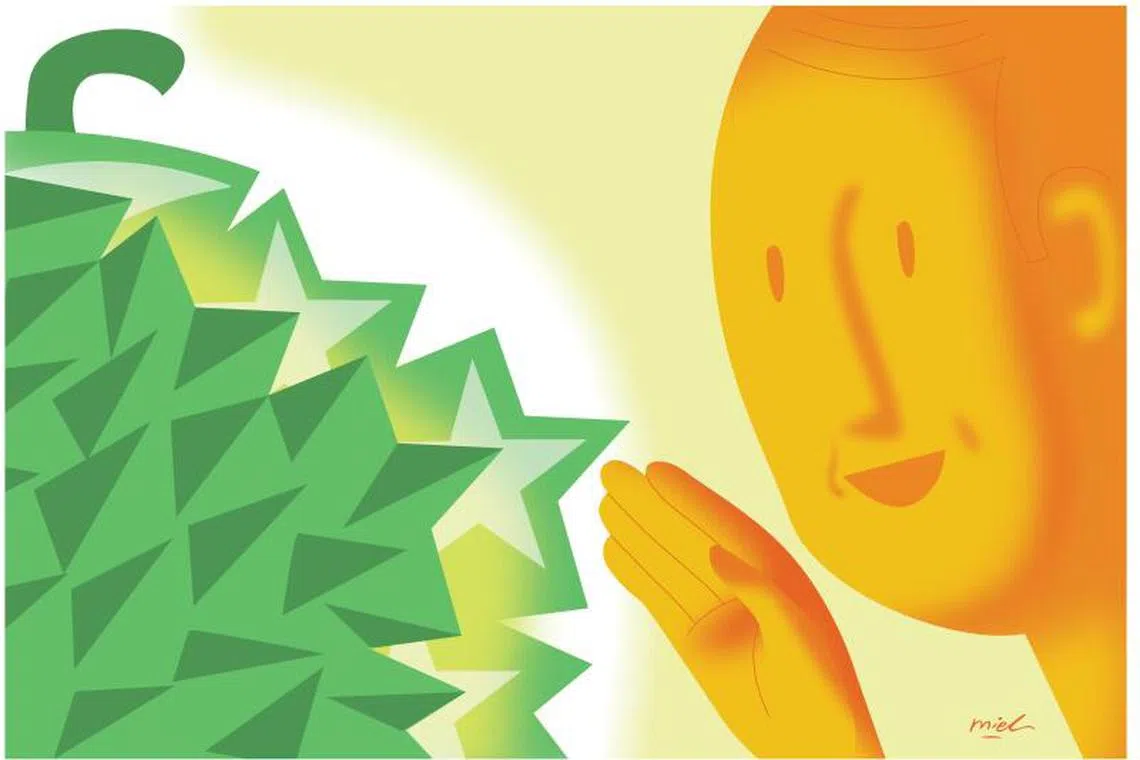

I watched an 81-second clip where, following separation from Malaysia, Mr Lee told Singaporeans to take heart. He compared Singapore to a durian – hard and thorny enough to repel bullies, but full of high-protein flesh inside.

“If they could have just squeezed us like an orange and squeezed the juice out, I think the juice would have been squeezed out of us, and all the goodness would have been sucked away,” he said.

“But it was a bit harder, wasn’t it? It was more like the durian. You try and squeeze it, your hand gets hurt. And so they say: ‘Right, throw out the durian.’ But inside the durian you know, is a very useful ingredient – high protein.”

In that same speech, Mr Lee assured Singaporeans that the country would one day become a modern metropolis.

Singaporeans now look back at those years with pride, but it was an immense challenge to build solidarity during those turbulent years when racial divisions ran deep.

The People’s Action Party (PAP) Government took a pragmatic approach with its policies, which among other things included:

Public housing policies that turned Singapore into a nation of home owners and gave people a stake in this country.

Ethnic quotas that were imposed in public housing estates so people of different races could mix.

Bilingual education in schools which ensured that Singaporeans would be able to communicate with one another, regardless of race.

Today, these policies are held up as the foundation of multiracialism and equality – values that Singapore holds dear.

What they did essentially was push Singaporeans to put aside their differences.

Singapore’s pioneer leaders built solidarity by expanding people’s idea of what constitutes “us” – giving Singaporeans a sense of shared fortune.

ST ILLUSTRATION: MIEL

New social compact

This part of our history is relevant today because a new generation of leaders is trying to build a fresh social compact with Singaporeans.

The fourth generation (4G) team led by Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong will soon take over.

In 2022, they launched the Forward Singapore exercise, reaching out to Singaporeans to try and figure out how our values, priorities and policies should shift and change for the future.

Their report will be published later in 2023, but finding a way forward can seem like a monumental challenge during a time of increasing polarisation. Our political landscape is also shifting, and adding to these concerns are inflation and global economic uncertainty exacerbated by geopolitical tensions.

Earlier this year in Parliament, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong highlighted three major global storms that Singapore has to be prepared for

“The current global situation, both strategic and economic, is graver than we have experienced for a very long time,” he said, reminding Singaporeans that we have survived difficult periods before.

It’s important to remember that.

The Semangat Yang Baru exhibition currently on at the National Museum is another timely reminder. It tells the story of Singapore between the 1950s and 1970s.

Beyond the contributions of Mr Lee Kuan Yew and other PAP pioneers, the exhibition spotlights a diverse cast of characters: from Singapore’s first chief minister David Marshall, who mooted the idea of a multiracial, multi-religious state in 1956, before the PAP took power; to Barisan Socialis’ secretary-general Lim Chin Siong, who is held up as an example of integrity and selflessness.

These examples show diversity has always been a part of Singapore’s multi-textured history.

Perhaps President Tharman Shanmugaratnam’s landslide win at the recent presidential election,

In the weeks after the election, Singaporeans have pored over the results, analysing how Singapore’s ninth president garnered such a commanding share of the vote.

His track record in Government and politics was given as a major reason, so too were his financial nous and international reputation.

In my view, his message of “Respect for all” was a big reason why Singaporeans overwhelmingly supported him.

He built solidarity by getting people to think beyond their differences and realise that in the end we all want the same thing – a Singapore where everyone is respected, regardless of background, political views, social status or skills.

The 4G team will have to do the same, and for now we’ll have to wait to see the specifics on how exactly they will do this.

For me, in times when differences are being capitalised and politicised across the globe, and may even seem intractable, I like to think about the tale of an unlikely nation that succeeded against the odds.

It is a reassuring reminder that in these turbulent times we walk in the footsteps of those who came before us.