Annoyed by restaurant playlists, master musician Ryuichi Sakamoto made his own

Sign up now: Weekly recommendations for the best eats in town

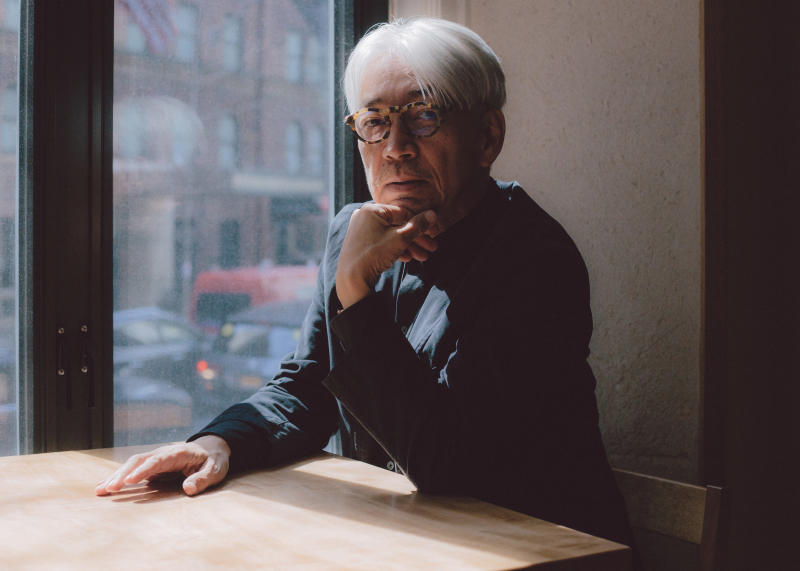

The prolific musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto at Kajitsu, a Manhattan restaurant where he created the music playlist.

PHOTOS: NYTIMES

NEW YORK (NYTIMES) - Last fall, a friend told me a story about Ryuichi Sakamoto, the renowned musician and composer who lives in the West Village. Sakamoto, it seems, so likes a particular Japanese restaurant in Murray Hill, and visits it so often, that he finally had to be straight with the chef: He could not bear the music it played for its patrons.

The issue was not so much that the music was loud, but that it was thoughtless. Sakamoto suggested that he could take over the job of choosing it, without pay, if only so he could feel more comfortable eating there. The chef agreed, and so Sakamoto started making playlists for the restaurant, none of which includes any of his music. Few people knew about this, because Sakamoto has no particular desire to publicise it.

It took me a few weeks to appreciate how radical the story was, if indeed it was true. I consider thoughtless music in restaurants a problem that has gotten worse over the years, even since the advent of the music-streaming services, which - you'd think - should have made it better.

In February, I went to Sakamoto's favourite restaurant, on 39th Street near Lexington Avenue, with my younger son. It is a split-level operation: On the second floor is Kajitsu, which follows the Zen, vegan principles of Shojin cuisine, and on the ground floor is Kokage, a more casual operation that incorporates meat and fish into the same idea. (A Japanese tea shop, Ippodo, occupies a counter towards the front of the street-level space.)

As soon as we sat down, the music pinned our attention. It came from an unpretentious source - a single, wide speaker sitting on a riser about 30cm off the floor, hidden behind a serving table. (We were downstairs in Kokage, but the same music was playing upstairs in Kajitsu.) I asked a waiter if the playlist was Sakamoto's. She said yes.

Sakamoto, 66, is exemplary perhaps not only for his music, but also for his listening, and his understanding of how music can be used and shared. He is a hero of cosmopolitan musical curiosity, an early technological adopter in extremis, and a kind of supercollaborator. Since the late 1970s, when he was a founding member of the electronic-pop trio Yellow Magic Orchestra, he has composed and produced music for dance floors, concert halls, films, video games, cellphone ringtones, and acts of ecological awareness and political resistance. (Much of this is detailed in Coda, Stephen Nomura Schible's 2017 film documentary about the musician.)

Some of what we heard at Kokage sounded like what Sakamoto would logically be interested in. There was slow or spacious solo-piano music from various indistinct traditions; a few melodies that might have been film-soundtrack themes; a bit of improvisation. Where there was singing, it was generally not in English. I recognised a track from Wayne Shorter's record Native Dancer, with Milton Nascimento, and a pianist who sounded like Mary Lou Williams, although I couldn't be sure. This wasn't particularly brand-establishing music, or the kind that makes you want to spend money; it represented a devoted customer's deep knowledge, sensitivity and idiosyncrasies. I felt generally stumped and sensitively attended to. I felt ecstatic.

'Normally, I just leave'

I found out that Sakamoto had enlisted Ryu Takahashi, a New York music producer, manager and curator, to help him with the playlist. My son and I met them both, as well as Norika Sora, Sakamoto's wife and manager, on a bright spring afternoon between services at Kajitsu, where the tobacco-earth smell of Iribancha tea permeated the dining room. Sakamoto was dressed in black down to his sneakers.

I asked if the story I'd heard was true. It was, he said. I asked if it would bother him if people knew. "It's OK," he said. "We don't have to hide."

He is not in the habit of complaining when he has a problem with music in public spaces, because it happens so often. "Normally, I just leave," he said. "I cannot bear it. But this restaurant is really something I like, and I respect the chef, Odo." (Hiroki Odo was Kajitsu's third chef and worked there for five years until March. Odo told me the music had been chosen by the restaurant's management in Japan.)

"I found their BGM so bad, so bad," Sakamoto said, using the industry term for background music. (BGM is also the title of a Yellow Magic Orchestra record from 1981.) He sucked his teeth. "Really bad." What was it? "It was a mixture of terrible Brazilian pop music and some old American folk music," he said, "and some jazz, like Miles Davis."

Some of those things, individually, may be very good, I suggested.

"If they have context, maybe," he replied. "But at least the Brazilian pop was so bad. I know Brazilian music. I have worked with Brazilians many times. This was so bad. I couldn't stay, one afternoon. So I left."

He went home and composed an e-mail to Odo. "I love your food, I respect you and I love this restaurant, but I hate the music," he remembered writing. "Who chose this? Whose decision of mixing this terrible round-up? Let me do it. Because your food is as good as the beauty of Katsura Rikyu." (He meant the thousand-year-old palatial villa in Kyoto, built to some degree on the aesthetic principles of imperfections and natural circumstances known as wabi-sabi.) "But the music in your restaurant is like Trump Tower."

I asked Sakamoto whether the exercise of creating a restaurant playlist was as simple as choosing music he liked. "No," he said. "In the beginning, I wanted to have a collection of ambient music - not Brian Eno, but more recent." He came to the restaurant and listened carefully as he ate. He and his wife agreed that the music was much too dark in mood.

"The light is pretty bright here," Sora said. "The colour of the wall, the texture of the furniture, the setting of the room wasn't good for enjoying music with darker tones, to end your night. I think it depends not just on the food or the hour of the day, but also the atmosphere, the colour, the decoration."

Takahashi reckoned that he and Sakamoto made at least five drafts before settling on the current version of the Kajitsu playlist. Some songs were too this or too that - too loud, too bright, too "jazzy".

Turning down the volume

It was also not very loud, and here we arrive at an issue that may concern older customers more than younger ones. Sakamoto objects to loud restaurant music and often uses a decibel meter on his phone to measure the volume of the sound around him.

He has composed original music for public spaces before, he said - a scientific museum and an advertising-agency building in Tokyo. He used light and wind sensors to change the music during the day. But the only experience he has had making playlists of the music of others, for other people, has been for family members.

He made one for his son when he was learning to play the bass guitar; Sakamoto carefully excluded bassist Jaco Pastorius, for reasons of personal taste, but his son found out about Pastorius a week later and scolded his father for the omission. Sakamoto made one for his father during a hospital illness. And he made one for his mother's funeral.

Was that, I asked, a collection of music she liked? Sakamoto paused and laughed and shook his head. "It was, kind of, my ego," he said.

Sakamoto and Takahashi plan to change their playlist with each new season. Odo's next venture, a bar named Hall and a restaurant named Odo, is scheduled to open in the Flatiron district in the fall. Sakamoto, again, has been retained as chief playlister.

Ryuichi Sakamoto's playlist:

1. Prairie Home Suite, Part 2 - The Sleeping Beauty

2. Threnody - Goldmund

3. Promenade Sentimentale - Vladimir Cosma

4. Light Drizzle - Chihei Hatakeyama

5. TWTGA - Bing & Ruth

6. The Flat - Johann Johannsson

7. And Still They Move - Colin Stetson and Sarah Neufeld

8. Graysmith's Theme - David Shire

9. I Love Music - Ahmad Jamal

10. Four Walls: Act One - John Cage

11. Some - Nils Frahm

12. Spartacus Love Theme - Bill Evans

13. Mistress - Nicolas Jaar

14. Lament - David Darling

15. When She Went Away - Max Richter

16. Empire I - Jon Hassell

17. wrong i - h hunt

18. Gentle Threat - Gonzales

19. India Song - Carlos D'Alessio

20. My Ship - Milli Vernon,

21. Armellodie - Gonzales

22. Ohgod - Vincent Gallo

23. Claudia, Wilhelm R And Me - Roberto Musci

24. Above The Treetops - Pat Metheny

25. Tarde - Wayne Shorter and Milton Nascimento

26. Peace Piece - Bill Evans

27. Variation On A Theme by _____ - Kyle Bobby Dunn

28. Replica - Oneohtrix Point Never

29. Cryo - Oneohtrix Point Never

30. Nanou 2 - Aphex Twin

31. Avril 14th - AWS

32. The Seasons, Prelude III Summer - John Cage

33. The Plum Blossom - Yusef Lateef

34. It Ain't Necessarily So - Mary Lou Williams

35. Circling - Nils Frahm

36. Day Two Three - F.S.Blumm & Nils Frahm

37. Only The Circle - Deru

38. String Quartet In Four Parts II, Slowly Rocking - John Cage

39. Veterans - Jason Moran

40. Ate Quem Sabe - Gal Costa

41. Garimpo - Nana Vasconcelos

42. Solaris - Cliff Martinez

43. The Shade - Cluster & Eno

44. Fur Luise - Cluster & Eno

45. Glide V - Peter Davison

46. Spiegel Im Spiegel - Arvo Part

47. Theme Of The Uprooting - Eleni Karaindrou Ensemble

48. Signals No. 1 - Goldmund

49. Valsa De Uma Cidade- Caetano Veloso

50. I Don't Stand A Ghost of A Chance With You - Thelonious Monk

51. Les Metronomes Detrauques - Regis Campo

52. My First Homage - Gavin Bryars