Breaking the silence on suicide: A mother opens up about the loss of her teenage son

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

SINGAPORE - Grief leaves its marks on the body.

For weeks after her teenage son died by suicide last year, Ms Elaine Lek, 54, wore thick jackets as she felt cold even in boiling weather.

She stopped driving for four months because of panic attacks that left her with heart palpitations and chest pains. She broke out in rashes and food tasted like dust.

It still takes a toll on her to recount how her son, Zen Dylan Koh, died on Oct 1 last year, a month before his 18th birthday.

Yet, even when the tears flood in, she wants to break the silence around this taboo subject.

Ms Lek, head of the global brand team at a tableware firm, questions why there is this silence, even while young people can easily find on the Internet methods to kill themselves, like Zen did.

"People talk about sex education in schools, but do they really talk about mental wellness? If we don't use the word suicide, how are we going to talk about it?" asks Ms Lek, who is married to Mr Koh Say Kiong, 58, a sales development director. They have another son who is 16.

Ms Lek applauds recent moves to decriminalise attempted suicide in the Criminal Law Reform Bill, which was read in Parliament earlier this month. It would destigmatise people who are already deeply vulnerable, she says.

Those opposed to the move say, though, that criminalisation could deter people from taking their own lives.

Clinical psychologist Lilian Ing, who works at Fernhill Consultancy, which offers psychology and counselling services, believes that decriminalising attempted suicide will remove some of the silence surrounding the act.

"Criminal stigma is part of a broader issue. We don't talk about death," says Ms Ing, who has worked with suicidal clients during her 25-year career.

"When someone wants to plan his death, we are so frightened and we feel so helpless that we would rather shut it down.

"We need role models who are willing to speak with searing honesty about the challenges we face in life."

But even if decriminalising attempted suicide encourages more persons at risk to open up and seek help, as she suggests, perhaps another question arises: How do we talk about suicide as a society?

MENTAL HEALTH CHALLENGES

Ms Lek is attempting to broach this taboo subject by opening up about her son's death.

She recounts how Zen seemed happy to see her on Sept 27 last year when she flew to Melbourne, where he was studying, and they had made plans to meet the next day.

But less than five hours later, he took his own life and died three days later in hospital.

She is struggling to come to terms with why he did so.

While he had experienced mental health challenges before, Zen initially settled down well in Melbourne. He moved there in February last year to enrol in a pre-university course at Trinity College in the University of Melbourne.

About half a year earlier, in September 2017, the former Anglo-Chinese School (Independent) student was struggling in his first year at Serangoon Junior College. He became moody and sometimes slept all day. He had relationship problems and had fallen out with some of his friends. His grades were declining.

One day, his parents found scalpel blades in his room. They had noticed self-harm marks on his arms, which he kept hidden under long-sleeved hoodies. Ms Lek later found out he had been taunted by schoolmates about those "barcode" cuts.

-

HELPING THOSE AT RISK

Ms Wong Lai Chun, senior assistant director of suicide prevention agency Samaritans of Singapore (SOS), shares some tips on how to be more aware of suicidal behaviour and how to help prevent it.

Warning signs

Suicide warning signs can be classified broadly into three categories:

1. TALK

Persons at risk may say things such as:

• "My family will be better off without me."

• "My life is meaningless anyway."

• "If you don't love me, I'll kill myself."

2. ACTIONS

They may give away treasured possessions and say goodbye to people around them.

They may research suicide methods or write suicide notes, including e-mails, diaries or blogs.

3. MOOD

They may display emotional outbursts showing anger, sadness, irritability or recklessness.

They may lose interest in things they may ordinarily be interested in, and express feelings of humiliation or anxiety.

How to help

• Asking someone if he wants to end his life does not increase the likelihood of it happening. It lets the individual know that he can talk about suicide and express his feelings freely.

• If you know of someone who is contemplating suicide, express your concern and talk to him in a caring and non-judgmental way.

• Loved ones may wish to suggest to individuals in crisis to approach professional support resources or accompany them to make an appointment if necessary.

• If someone does not wish to seek help, concerned third parties may ask for his consent to be referred to SOS. Third-party referrals can be made through the 24-hour SOS Hotline (1800-221-4444) and e-mail Befriending service (pat@sos.org.sg).

• When someone is in imminent danger due to a suicide crisis, call 995 for an ambulance or accompany the individual to the A&E department of the nearest local hospital immediately.

She took Zen to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him as having Attention Deficit Disorder, characterised by inattentiveness and impulsivity. He was given medication and his situation seemed to stabilise.

But he and his parents felt he would do better in a different environment and they eventually picked Trinity College together.

DOWNWARD SPIRAL

A natural athlete, Zen enjoyed skateboarding around Melbourne and going to the gym.

Robert (not his real name), 17, Zen's housemate, says: "My first impression of Zen was that he was a popular, good-looking kid."

Zen had a goofy sense of humour, sometimes putting on a mud mask to spook his friends.

He was also generous. A friend, Aurelia (not her real name), 18, recalls how he gave her his $250 graphing calculator in junior college as she could not afford one.

But there were darker undercurrents behind some of Zen's friendships. Jenny (not her real name), 17, a fellow student in Melbourne, says she was drawn to Zen as he seemed like someone she could talk to.

But she and Zen, who were platonic friends, sometimes sent each other photos when they had cut themselves.

"Sometimes, the physical pain distracts me. It's a coping method, but it's not good. Still, it's important that people know they're not alone. We would try to support one another," she says.

Once, Zen helped her get through what she described as a mental breakdown. And sometimes, he would text her late at night saying he was sad, and she would go talk to him.

Other friends who rallied around Zen included Robert, who has bipolar disorder, and Aurelia, who has engaged in self-harm before.

Psychiatrist John Wong, from National University Hospital (NUH), warns of possible "negative contagion" in groups with individuals who face mental health challenges.

"It is not uncommon for vulnerable teenagers in similar emotional and social situations to feel for and identify with one another... These vulnerable teens may meet in clinics or hospital inpatient wards or on social media, bonded by a common identity and purpose," says Associate Professor Wong, who is head and senior consultant of NUH's department of psychological medicine.

"This could trigger a negative contagion effect leading to a downward spiral of emotional distress and hopelessness."

MEDICATION RISKS

Around June last year, some of Zen's friends noticed that he seemed depressed. They eventually called Ms Lek to let her know.

They also spent as much time with Zen as possible, ensuring he was not left alone for long.

By July, back in Singapore, Ms Lek realised that Zen was engaging in self-harm again after discovering a secret Instagram account of his from his old phone, where he had posted images of his self-harm.

"There were several 'likes' and even comments like, 'We'll do it together,'" says Ms Lek, her voice clouded with pain.

Although she and her husband visited Zen regularly in Melbourne and were in frequent contact with him, he did not tell her about his self-harm, even when queried.

"He would always tell me, 'Don't worry, mum, I'm okay,'" she says.

In early September, during a break from school, however, she took Zen to another psychiatrist in Singapore, as the first one he saw in 2017 was not available.

He was diagnosed with Generalised Anxiety Disorder and mild depression and prescribed an anti-depressant called Lexapro.

Ms Lek says: "He was glad about his diagnosis because he did not know till then what he was suffering from."

But she expressed concern when the psychiatrist reportedly increased Zen's dosage from 2.5mg to 10mg after about a week. He allegedly told her it was routine.

She claims she was not told of any possible side effects except insomnia and loss of appetite.

But Lexapro, like other antidepressants in the SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) class of drugs, has a sting in its tail for a small group of adolescents.

A spokesman for Singapore's Health Sciences Authority, noting that medical conditions such as depression may be associated with an increased risk of suicide, says: "While SSRIs are used for the treatment of depression, they are known to be associated with a possible increased risk of suicidal thinking and behaviour in some children, adolescents and young adults."

The spokesman recommends monitoring patients for suicidality and unusual changes in behaviour, particularly at the start of treatment and when there are changes in dosage.

THE LAST MONTHS

Ms Lek says Zen started behaving uncharacteristically when he went back to Melbourne after being prescribed Lexapro on Sept 4. He ignored his parents' texts and calls, went on a A$500 (S$480) online shopping spree and had erratic mood swings.

Although she believes that Lexapro tipped Zen over the edge, not everyone agrees.

Aurelia says that during the last few months of his life, Zen called her to talk about how he was feeling sad and at a loss.

Robert says that from the time he first knew Zen in February last year, Zen had expressed suicidal thoughts "on multiple occasions".

He tried different ways to help Zen. He asked Zen to call a suicide hotline. He knew that Zen had seen a psychiatrist. Once, when Zen asked what would be a good way to die, Robert joked: "Smoking will kill you in 20 years."

In late September, another friend of Zen's called Ms Lek, saying her son was unwell and he had bought a rope. Ms Lek had also heard about a past incident where Zen banged his head against a wall repeatedly in apparent frustration.

She flew to Melbourne as soon as she could, on Sept 27. She and her husband had already planned to take turns to stay with Zen for the last few months of his course. She had arranged for psychologists and counsellors to see him.

That same day, Robert had spoken to their accommodations manager, who pledged to notify the school's welfare office the following day about getting help for Zen.

-

Helplines

•Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444

•Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

•Care Corner Counselling Centre (Mandarin): 1800-353-5800

•Tinkle Friend: 1800-274-4788

Yet, when Ms Lek met Zen, he was his usual loving self, she says.

They had dinner together; he had steak, his favourite meal. They parted ways at about 9pm. Zen said he was going to the gym with his friends and she planned to take him and his buddies out soon.

But at 1.30am on Sept 28, she received an emergency call from the accommodations manager, Ms Ivon Tio, 31. Ms Lek ran from her hotel, five minutes away, to Zen's residence.

Robert, Ms Tio and Zen's room-mate, who had raised the alarm, took turns doing CPR on Zen until the paramedics arrived and took him to hospital.

Ms Lek cuddled her son as he convulsed with seizures on the hospital bed.

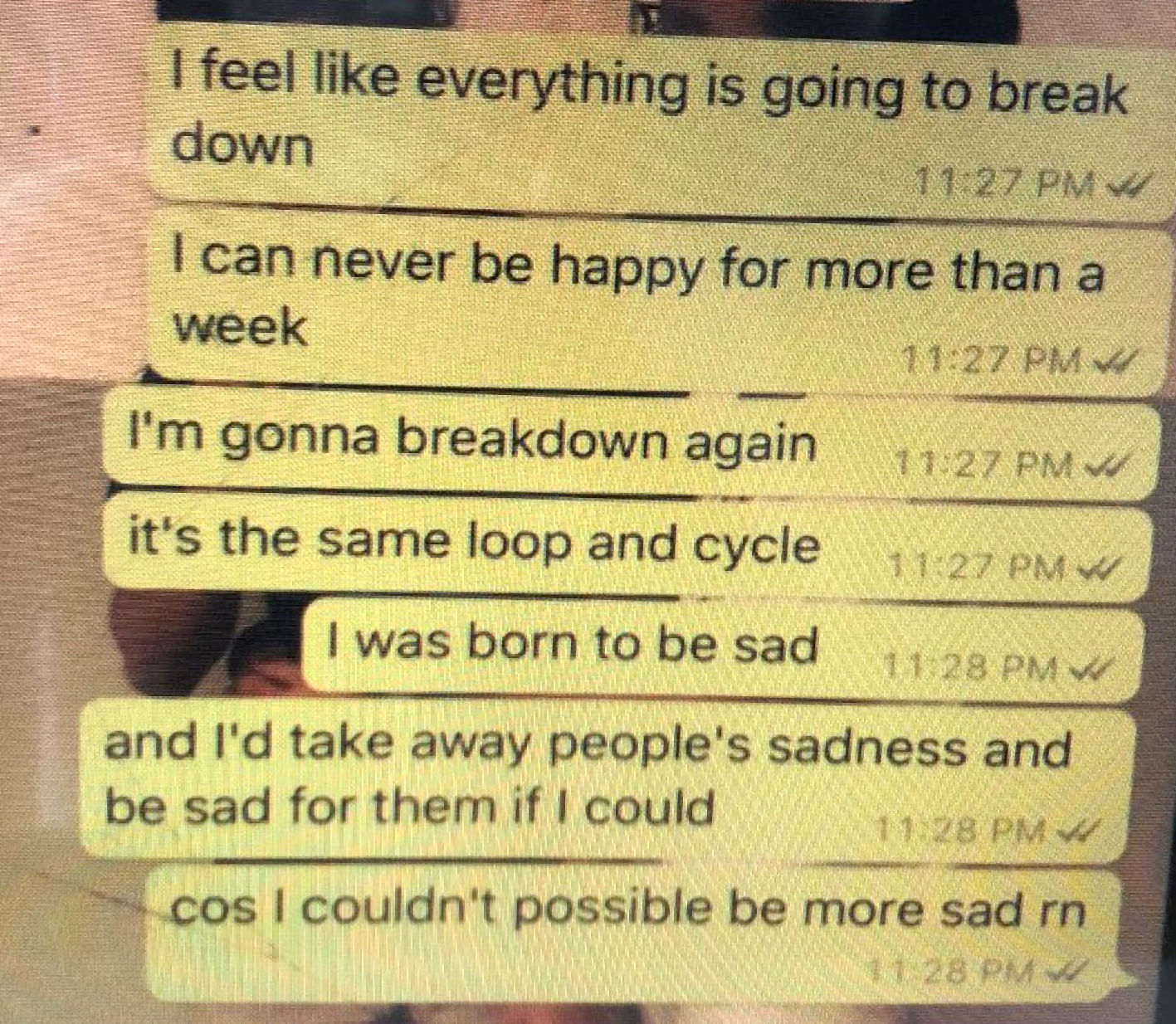

As he lay in the Intensive Care Unit for three days, she scrolled through his phone and found WhatsApp messages from Zen to a friend, saying he was "born to be sad". She had not known the extent of the distress he had kept from her.

She also found three WhatsApp messages he had sent before he killed himself, showing what he intended to do. The recipients did not or could not help him.

Ms Lek spoke to Zen one last time: "I thanked him for choosing me to be his mummy for the past 17 years and 11 months... I told him mummy forgives him and asked him to forgive me too. Tears were rolling down his cheeks and that night, he was brain dead."

On Oct 1, Zen died. His parents donated his organs to six recipients.

LIFE AFTER ZEN

Ms Lek has decided to let go of the anger she felt towards Zen's psychiatrist. She forgives the friends who could not help him, or who kept his condition secret, though she warns that professionals should be contacted as soon as possible for mental health issues.

She says: "You may think you are 'betraying' your friend's secret for five minutes, but you would be saving a life."

She wants peace.

On Jan 1, she and her family launched the Zen Dylan Koh Fund, in partnership with non-profit organisation Limitless, to raise funds to counsel vulnerable youth.

Zen wanted to be a psychologist to help others who felt as sad as he did, she explains. "I want to honour the memory and legacy of my son, and my love for him," she says.

She had her first tattoos in memory of Zen on her forearms. When she holds herself, it feels as if he is comforting her, she says.

On his birthday, a month after he died, she wrote a letter to him asking for forgiveness for the genes she had passed to him. She has found out that eight relatives in her family tree had mental illness of some kind.

Every evening, she and her husband light a candle for Zen. They chat about him and talk to him.

"Even if we're travelling, we will light a candle for as long as we live," she says.