FICTION

UNTOLD NIGHT AND DAY

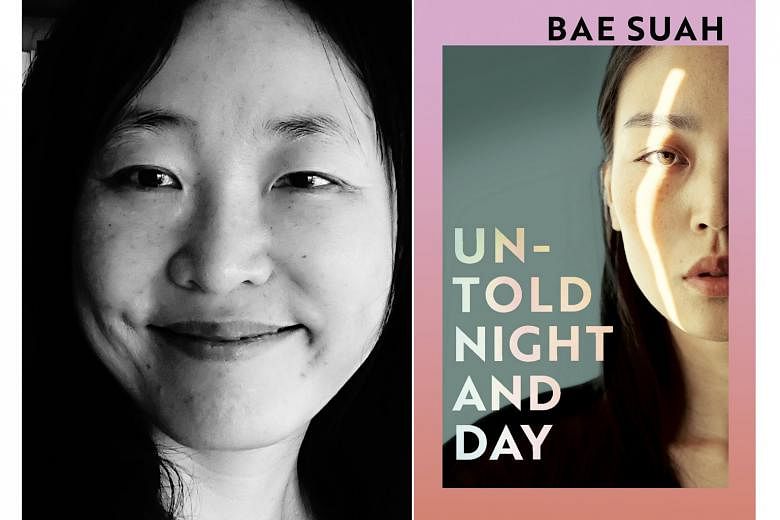

By Bae Suah, translated by Deborah Smith Jonathan Cape/ Hardcover/ 160 pages/ $25.95/Books Kinokuniya/ Available at bit.ly/ Untold_Night/4 stars

Bae Suah, who has published more than a dozen novels and short stories since 1993, is one of South Korea's most inventive experimental writers.

She stays true to form in Untold Night And Day, blurring the distinction between black and white, and night and day, in an ethereal labyrinth where life unfolds in strange repeated loops and the slippery edges of reality start to fray.

What begins as a calm breeze - Kim Ayami, a 28-year-old actress turned administrator at an audio theatre for the blind in Seoul, ponders her future after the theatre shuts down - soon unravels into trippy, psychedelic chaos like a fever dream on a midsummer night.

Bae paints an apocalyptic vision of Seoul's scorching, unbearable summer, in which "the city was like an animal being slowly smothered beneath a heap of steaming earth" and where "breathing was a train headed for disaster".

Over the course of 24 hours, Ayami has dinner with a former boss in a pitch-dark dining room - served by blind wait staff - discussing art and poetry. They then wander the sweltering streets of Seoul in search of their missing friend Yeoni.

In a parallel storyline, Kim Buha, who had wanted to be a poet but ended up as a temp at a pharmaceutical company, is also acquainted with Yeoni and finds his way to the audio theatre.

Untold Night And Day is a novel of existential crises and the search for one's identity. Says Ayami: "I'd realised that I, yes I who had pitied them was pitiful myself, a pitiful person who'd also always failed in convincing others."

Bae also pays tribute to the persecuted Iranian writer Sadegh Hedayat, referencing his celebrated 1936 magnum opus The Blind Owl throughout the story.

The book, about a young opium addict who spirals into despair and insanity after he loses a mysterious love, remains banned in Iran over its "anti-religious" themes.

Both writers are clearly adept at breaking down traditional storytelling arcs and rebuilding structurally undetermined novels.

Untold Night And Day, first published in Korean in 2013, is a high-wire masterstroke in storytelling, broadening worlds beyond the five senses to disorient and yet somehow make sense at the same time.

Masterfully translated by Deborah Smith, who had also worked on Han Kang's The Vegetarian, which won the Man Booker International Prize in 2016, it will sit right at home in a literature class or as an abstract play adapted for the stage.

Almost every sentence deserves to be dissected and pored over, and readers who pick this up should not expect a casual, easy read.

Not that this was Bae's intention to begin with. She says: "What I wanted to write was not something resembling a calm landscape. It was the point where the mind explodes, close to the secret and intense chaos."

If you like this, read: At Dusk by Hwang Sok-yong, translated by Sora Kim-Russell (Scribe, 2018, $22.95, Books Kinokuniya, available at bit.ly/Dusk_SH). Another book titled after a time of day by another eminent South Korean writer. Hwang's melancholic prose shines through in At Dusk, juxtaposing the nostalgia of a bygone era and the present-day struggles of South Korean youth in a soulless modernity.

- This article includes affiliate links. When you buy through affiliate links in the article, we may earn a small commission.