Digging deep into Vietnam's forgotten trauma

From famine to war, Nguyen Phan Que Mai weaves into her epic novel The Mountains Sing stories of what her family and friends went through

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

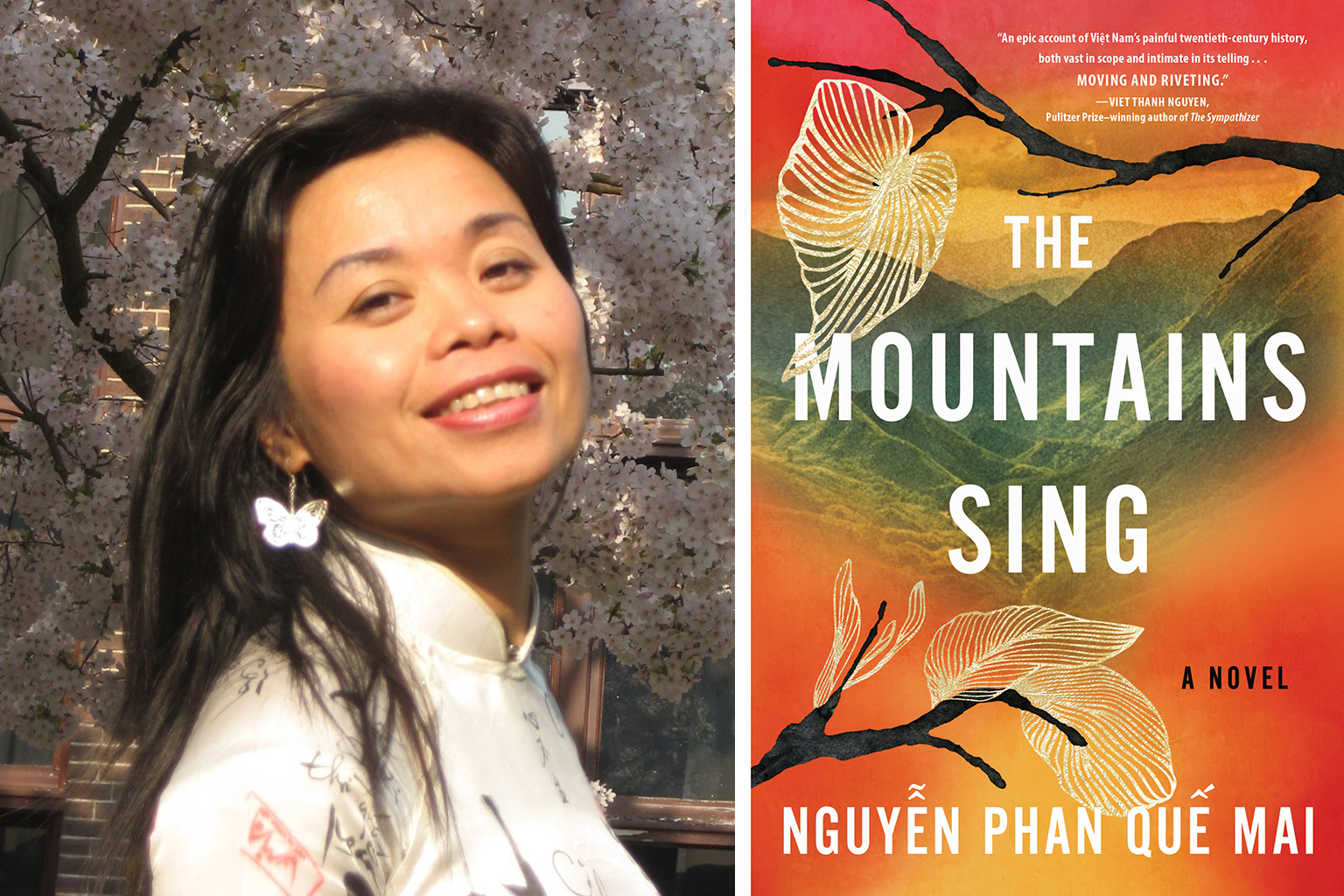

Nguyen Phan Que Mai (left), who took seven years to write The Mountains Sing (right)

PHOTO: VU THI VAN ANH

Once, Vietnamese writer Nguyen Phan Que Mai's friend told her a story about her grandmother. During Vietnam's 1950s Land Reform, the friend's grandmother was accused by the Communists of being a rich landowner and forced off her family's farm.

She fled to Hanoi with at least six of her children, but they had no food or money, so she began to give them up. She left each child with a stranger along the way. In Hanoi, she found work as a servant, saving money until she could return and collect her children.

Que Mai, 47, knew neither of her grandmothers. Both died before she was born, one in childbirth, the other in the Vietnamese famine of 1945, when one million to two million people are thought to have starved to death.

Growing up, she longed for a grandmother who could have told her the stories of her people. As a novelist, she sought out such stories from her family and friends and wove them together into a novel, The Mountains Sing, a tragic multi-generational history of Vietnam.

"If you talk to any Vietnamese family, you will find that the things that they went through could be written into an epic novel," she says over Skype from Munich, where she is spending the coronavirus lockdown with her diplomat husband and two children.

They are usually based in Jakarta, but flew to Munich, where her daughter was doing an internship, during the onset of the pandemic.

"I kept thinking about the separation that our family had to experience in the past," says Que Mai, whose family had been split up during the partition of Vietnam and whose uncles wound up fighting on opposite sides of the Vietnam War. "I insisted that we had to come here to be together."

Que Mai is acclaimed for her Vietnamese poetry, but The Mountains Sing is her first novel in English. She chose to write it in a language she learnt only in eighth grade because of the dearth of translated literature by Vietnamese writers.

Most of the acclaimed narratives from the Vietnamese perspective are by Vietnamese-Americans, such as Viet Thanh Nguyen, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sympathiser (2015), who was so impressed by the manuscript of The Mountains Sing that he sent it to his agent to get it published.

It took Que Mai seven years to write The Mountains Sing, which was first inspired by a conversation she had with a friend who had been caught up in bombings during the war. The first time he got on an aeroplane, the sound of the engines caused him to relive this experience and he would not stop screaming until he was taken off the plane.

The Mountains Sing opens with American bombers shelling Hanoi, as the narrator, a young girl nicknamed Guava, desperately searches with her grandmother for a shelter.

Guava's parents are away fighting the war. She is raised instead by her grandmother Dieu Lan, a tough trader who tells her stories from her own past: the brutality of the Japanese Occupation, the famine and the Land Reform, events which have often been glossed over in a history overshadowed by the Vietnam War.

Gradually, Guava's mother and uncles return from the war, each scarred and repressing horrific stories of their own.

Dieu Lan tells Guava: "We're forbidden to talk about events that relate to past mistakes or the wrongdoing of those in power, for they give themselves the right to rewrite history. But you're old enough to know that history will write itself in people's memories, and as long as those memories live on, we can have faith that we can do better."

Says Que Mai: "In Vietnam, the official viewpoint is that we won the war, so there's no trauma. There's no culture of mental health, there's little support for people with mental health issues. So people with trauma have PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), they are forced to bury their trauma and the process of healing is very, very difficult. I saw the need to document it."

Que Mai was born in the village of Ninh Binh in North Vietnam, two years before the Vietnam War ended in 1975. When she was six, her family moved to Bac Lieu, a town in South Vietnam.

As Northerners migrating to the South, they were regarded as invaders. "They used to throw rocks through the roof of our home, and I was called all types of names," she recalls. "So I didn't have friends in the beginning."

She spent her childhood doing labour - helping her mother sell rice, going to the field after the harvest with her brothers to pick up leftover rice and potatoes, and catching fish in the streams. "I think all children in Vietnam at that time had to work," she says. "I didn't see it as a duty as such. I took pride in it."

The most precious possession in her family was a bookshelf, and she read the handful of books on it so often that the covers fell off.

But though she wanted to be a writer, her parents and brothers dissuaded her because of their poverty. She wound up studying business management in an Australian university on a scholarship.

She spent several years working for international organisations, including United Nations agencies, to foster sustainable development in Vietnam, before returning to her writing dream at the age of 33.

She is now working on her next novel, about the Amerasian children fathered by American soldiers with Vietnamese women during the war. Abandoned and deemed the children of the enemy, they face a great deal of discrimination.

She admits that when she was a child, she once joined in the insulting of an Amerasian boy in her neighbourhood, something which she feels guilty about today. "They too are victims of the war and they have been forgotten. I want to tell their story."

• The Mountains Sing ($32.05) is available from bit.ly/MountainsSing_Nguyen

• This article includes affiliate links. When you buy through affiliate links in the article, we may earn a small commission.

This article contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn a small commission.