Culture Vulture: Darkness lurks in children's literature

Revisiting the stories written by Roald Dahl and Enid Blyton, one finds cruelty, spite, racism and sexism in the tales

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

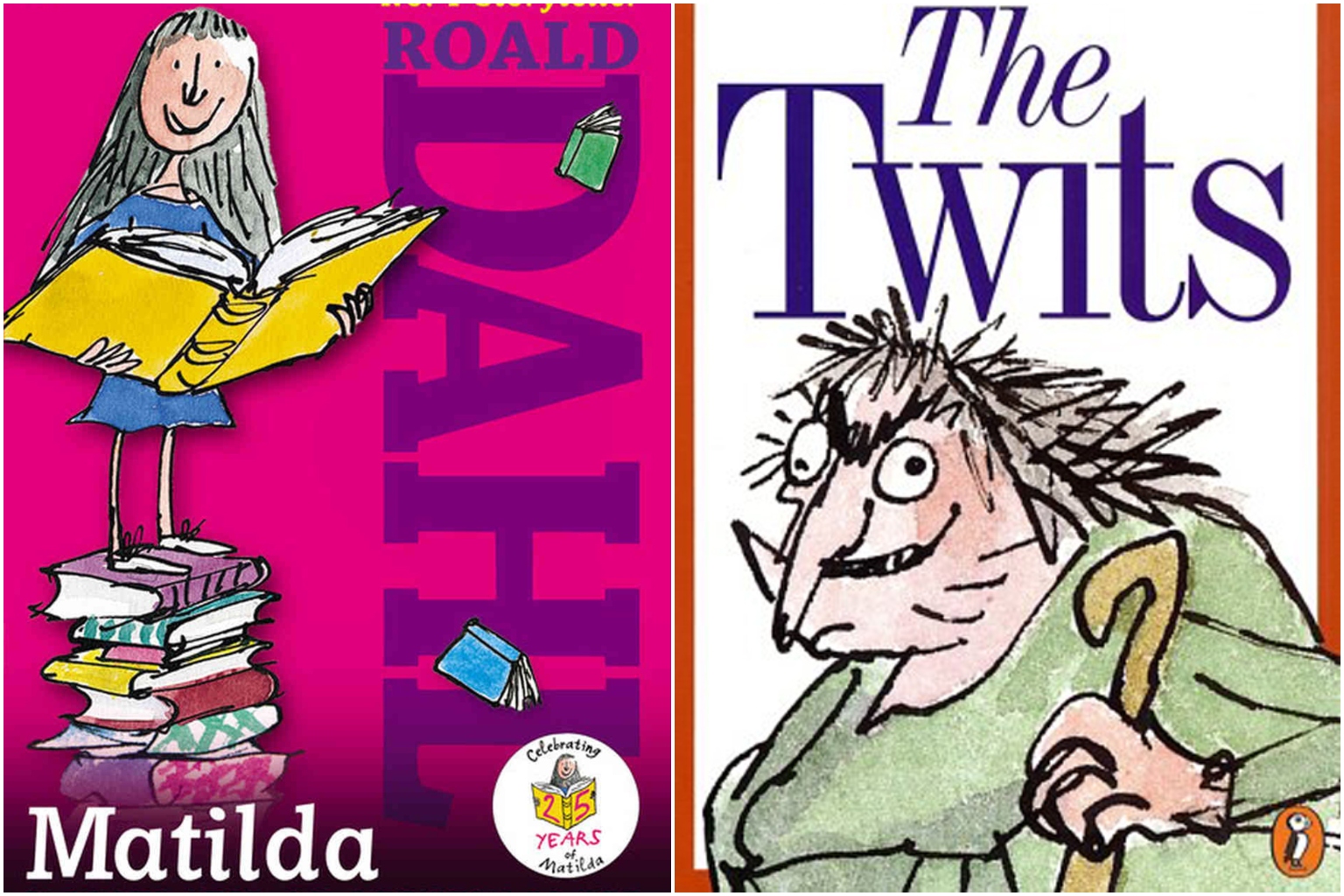

Matilda and The Twits by author Roald Dahl.

PHOTOS: PUFFIN CLASSICS, PENGUIN BOOKS

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE - While rummaging through a cupboard at home recently, I stumbled across some old paperbacks by Roald Dahl and Enid Blyton.

These two authors were responsible for countless hours of unadulterated joy while I was growing up - and so I decided the best thing to do would be to shatter my childhood illusions by revisiting them with all the hard scrutiny of a cynical adult.

Dahl's books, as expected, hadn't grown stale as Blyton's. Leafing through his books as an adult, I gained some new insights.

His narrators, to my surprise, don't just relish describing scenes of cruelty and spite - they have a talent for it.

In Matilda (1988), for example, there is a scene where the tyrannical headmistress Miss Trunchbull lifts a pupil up from the floor by his ears. Speaking with glee, she says she is certain his ears have been damaged permanently.

"Eric's ears will have stretched quite considerably in the last couple of minutes! They'll be much longer now than they were before. There's nothing wrong with that... It'll give him an interesting pixie look for the rest of his life."

To a child, Miss Trunchbull might seem like a brutal, inchoate monster - but as an adult, I'm struck by how finely Dahl describes her spite.

Then there is The Twits (1980), whose title characters are a husband and wife who play nasty tricks on each other.

The revolting couple somehow end up glued headfirst to the floor, and after days of being upside down, their heads shrink into their necks and their necks into their bodies, which finally disappear so only their clothes are left.

When I had the book read to me at the age of six, I was fascinated by the idea of turning a house upside down by gluing all its furniture to the ceiling. It never occurred to me, not until recently, to see the Twits as malicious or feel sorry for them.

Could "cruelty" in fiction seem less shocking to young readers because they already live in a world where everything seems monstrous and terrifying? Could the powerlessness of childhood make children desire the humiliation of others - fictional villains included - as a way to cope with their own vulnerability?

Dahl had a wonderful imagination and a lively style. And his most sympathetic adult characters often have a child-like excitement about them - note how he often uses the verb "cried", more animated than "said", when they are speaking.

One vital ingredient of Dahl's writing was his dark sense of humour. The stories wouldn't have worked half as well with children if they weren't so terribly wicked.

The late American illustrator Maurice Sendak didn't like Dahl at all. "The cruelty in his books is off-putting. Scary guy," said the then 83-year-old in his final Guardian interview. "I know he's very popular, but what's nice about this guy? He's dead, that's what's nice about him."

Dahl's "cruelty", however, makes sense when we consider Sendak's own salient observation about how complicated children are.

"There's a cruelty to childhood, there's an anger."

I've come to realise that another reason Dahl's stories went down so well with children is that his powerful child protagonists often have anger brimming inside them - and which child doesn't? Think Matilda, who moves objects with her mind, and the girl in The Magic Finger who turns her neighbours into winged creatures.

Happily, Dahl's popularity has endured, buoyed by television and stage adaptations such as Matilda The Musical, which comes to Singapore on Thursday (Feb 21).

Another popular - if divisive - children's writer was Enid Blyton, who wrote more than 600 books for children in her lifetime.

Unlike Dahl, she paints a sunny picture of a world of middle-class children who go on adventures, visit the seaside and dig into generous helpings of scones with lashings of ginger beer.

They were probably just as much an escapist fantasy for me - a child growing up in the 1990s halfway across the world - as they were for British readers in the 1940s, who were living in the throes of World War II.

While Blyton's books have thrilled generations of children, they have also been lambasted for their cardboard characters, limited vocabulary and mechanical quality.

People have rightly objected to the shades of class snobbery, racism and sexism in the stories - The Three Golliwogs (1944), about three characters named Golly, Woggie and Nigger, being one particularly offensive example.

Blyton, who was born in Victorian England in 1897 and died in 1968, could credit her commercial success (offensive "-isms" aside) to the very factors underlying the criticism: The repetitive nature of her work is precisely what speaks to a child's desire for comfort and familiarity. Reading her books, you know you are in safe territory.

Armchair psychologists have suggested that Blyton was good at writing for children because she was, in many ways, like a child herself, underneath the public veneer which she carefully polished right down to her famous signature.

Her younger daughter Imogen found her approach to life "quite childlike... She could also sometimes be almost spiteful like a teenager".

The BBC's fascinating biopic of the author, Enid (2009), suggests that as an adult, Blyton still suffered from the trauma of her parents' divorce. Played by Helena Bonham Carter, she is depicted as an emotionally stunted woman who hides from the unpleasant things in life.

We also learn that she had an underdeveloped womb - like that of a 13-year-old girl - and had to receive hormone injections before giving birth to her daughters.

Then came the infidelities, divorces and remarriages, and Blyton's alleged attempts to not only stop her former husband from seeing their children, but also ruin his career.

Literature undergraduates with a psychoanalytical bent would have a field day with Blyton if they weren't so busy turning up their noses at her.

Still, what does this all mean for the rest of us? Why all this fuss over children's books - let alone children's authors?

If I've learnt one thing from this exercise, it is that even though Dahl and Blyton's stories are often funny and jolly, darkness - be it on the page or in their lives - was never far off.

The refuge one finds in literature can only ever be temporary.