Ultrasonic bug repellents, weight-loss noodles: Why is TikTok Shop so strangely addictive?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

TikTok content creators like Mr Jotham Lim are resurrecting the shopper-tainment TV channels of old.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

- TikTok Shop's popularity has surged; shoppers increased by 87 per cent and livestream GMV by 90 per cent in July compared with the previous year.

- TikTok creators earn significant income through livestreams and affiliate links, with some deciding to leave their corporate jobs to stream full-time.

- TikTok Shop creates a "fear of missing out" with limited-time deals, which pushes viewers to buy.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – Mr Jotham Lim spends six to seven hours a day live-streaming, selling goods such as serums for hair loss and anti-hangover supplements from the comfort of his home.

The 35-year-old “live seller”, who makes between $20,000 and $30,000 each month, is part of TikTok’s fast-growing army of creators who are turning social media scrolling into social shopping, blurring the lines between entertainment and commerce.

According to a TikTok spokesperson, the company has seen an 87 per cent year on year increase in the number of shoppers on TikTok Shop in July, without revealing actual figures.

Gross merchandise value (GMV), or the total value of merchandise that is sold for live streams, has surged by 90 per cent over the same period, adds its spokesperson. The number of active local brands on the platform has also grown 58 per cent year-on-year in July.

In Singapore, an average of 2,800 TikTok Shop live streams took place every day in July.

As one scrolls through TikTok, posts by creators containing affiliate links are the most visible manifestation of social shopping.

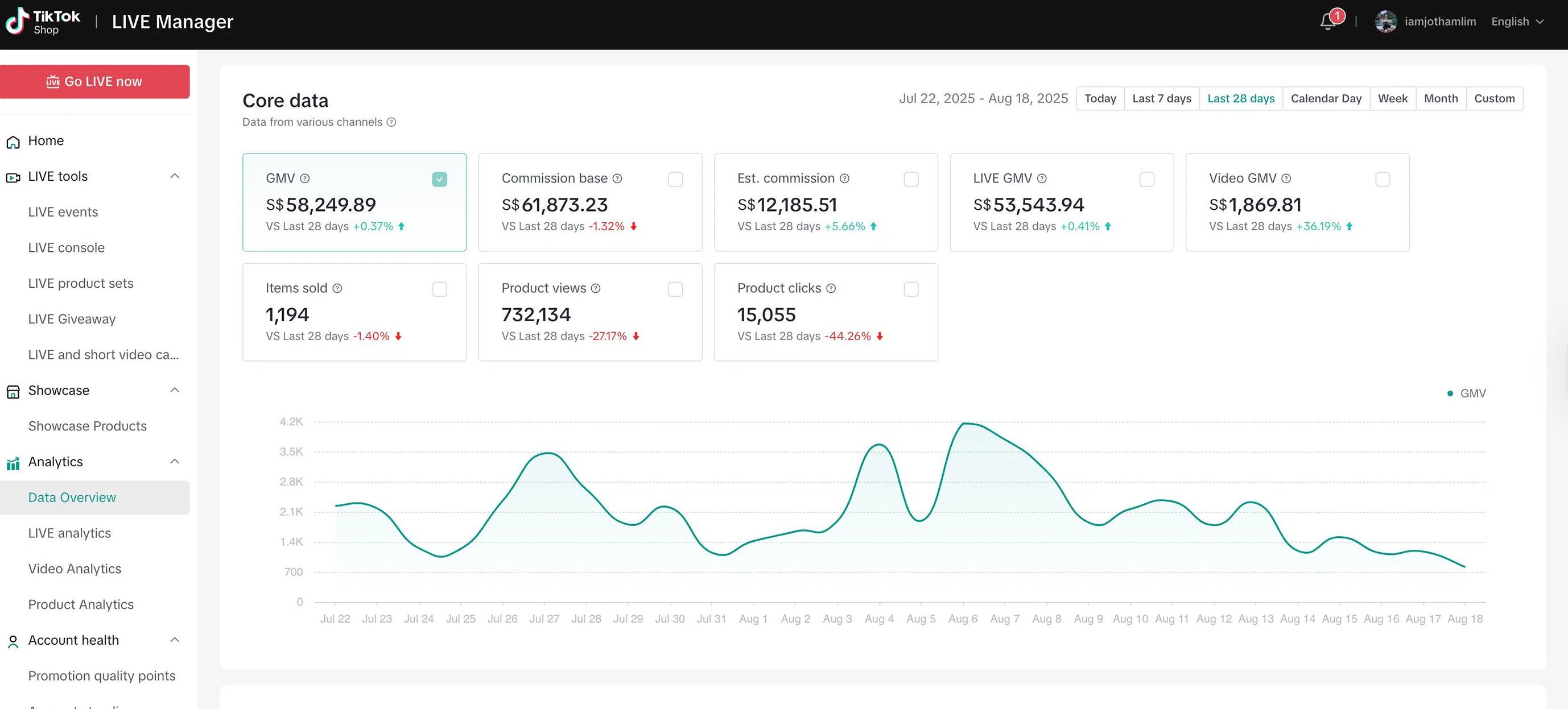

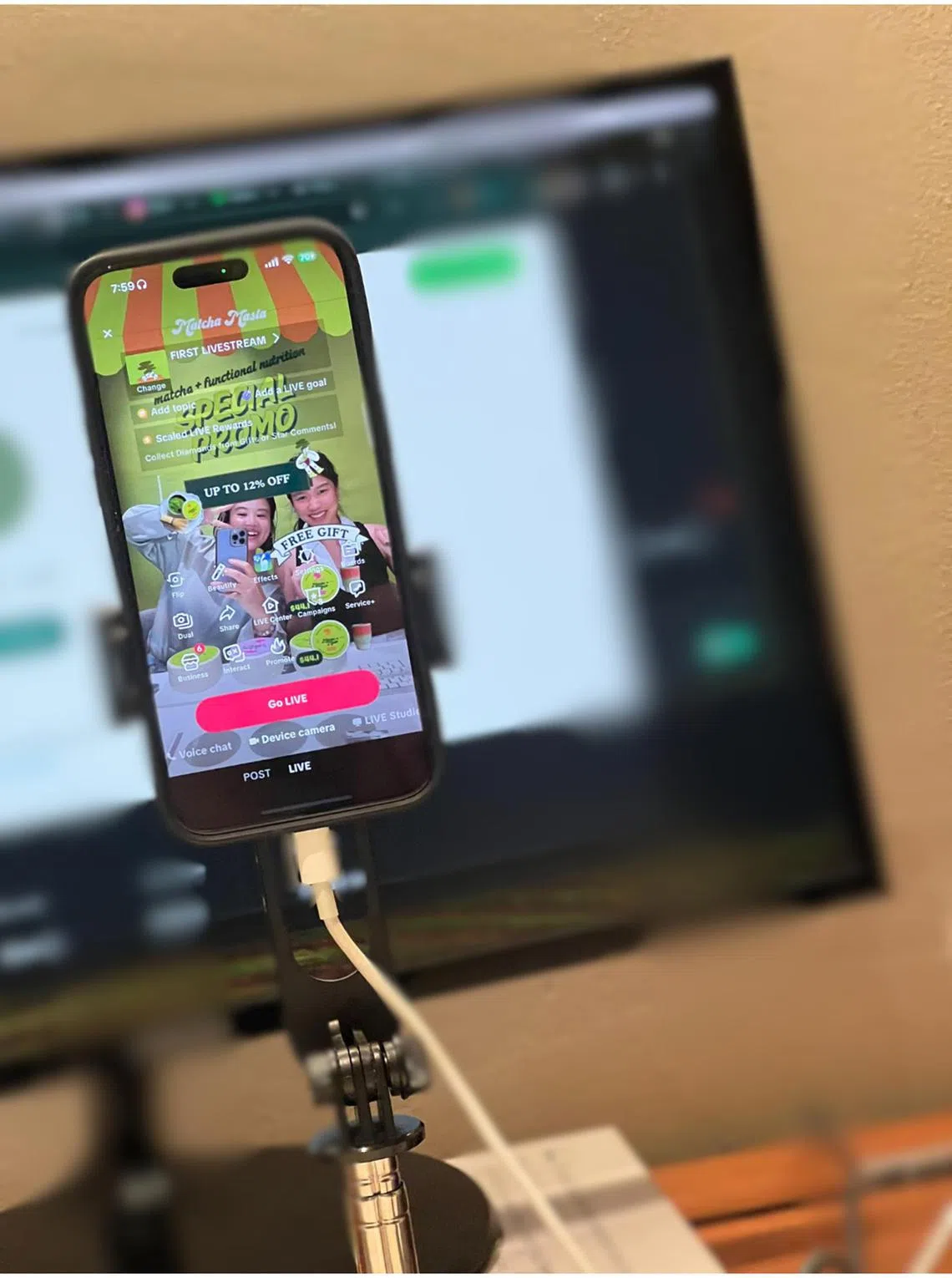

The dashboard used by creators selling products through TikTok Shop.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF JOTHAM LIM

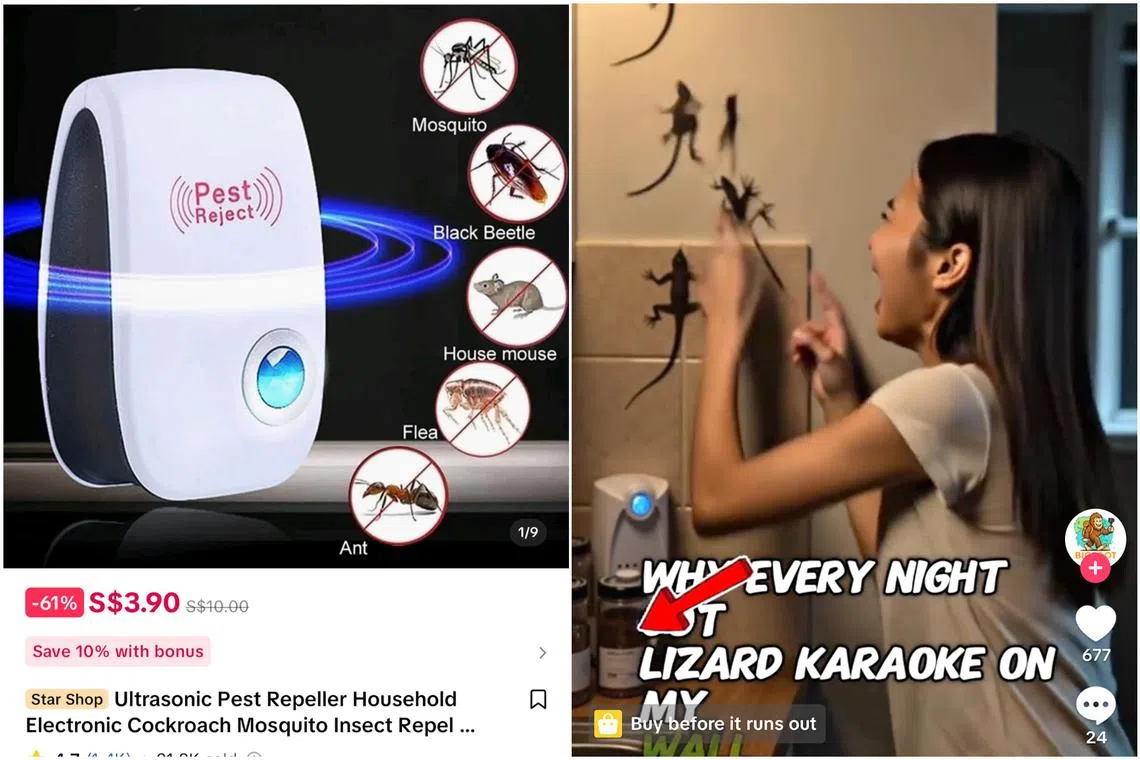

These posts feature a broad range of goods, from viral oddities reliant on video marketing such as ultrasonic pest repellents, to noodles and massage chairs from well-known brands like Haidilao and Osim.

“Guys, I bought this and, three weeks later, look at all the ants that are dead underneath my table,” gushes one TikTok user, marvelling at a $3.90 ultrasonic pest-repelling device available via an affiliate link in the same video. “Just click on this link to order.”

But buyer beware, as such devices have been criticised for their lack of scientific backing by the United States Federal Trade Commission and multiple laboratory studies.

Whether you hit the buy button, creators say the real money lies in live streams, where the revenue from each stream dwarfs the commission one makes from a short video post.

For example, Mr Lim says sharing a post with a product link typically garners less than 5 to 10 per cent of what he would earn from a live stream. He says the $20,000 to $30,000 he makes monthly comes from platform commission fees and retainer fees from the men’s health brand he works with.

“It forms a habit,” says Mr Lim, who notes that a growing subset of TikTok users are becoming repeat visitors to shopping live streams because of the allure of discounts, giveaways and interaction with hosts.

Such social shopping is unlike other e-commerce platforms such as Amazon or Shopee. Consumers often do not enter TikTok with a shopping list at the ready.

“The main intention for people going on the app is entertainment,” says Dr Crystal Abidin, a professor at Curtin University in Perth, Australia, who studies influencer culture and social media. “It is very seamless to go from watching a piece of entertaining content to clicking through to payment in as frictionless a manner as possible.”

Big bet on e-commerce

TikTok is one of the main players behind the rise of social shopping in South-east Asia.

PHOTO: TIKTOK SHOP MALAYSIA

The rise of social shopping has to do with TikTok’s Chinese origins. China’s major social platforms have a shopping component built into them that blurs the lines between entertainment and commerce.

Outside China, major platforms such as YouTube and Instagram have traditionally focused on advertising revenue instead, making the rise of social shopping more a carefully stage-managed process than an organic development.

In Indonesia, sellers on TikTok Shop by Tokopedia were asked to create influencer-style videos and live streams to promote their products, American news outlet Rest of World reported in July.

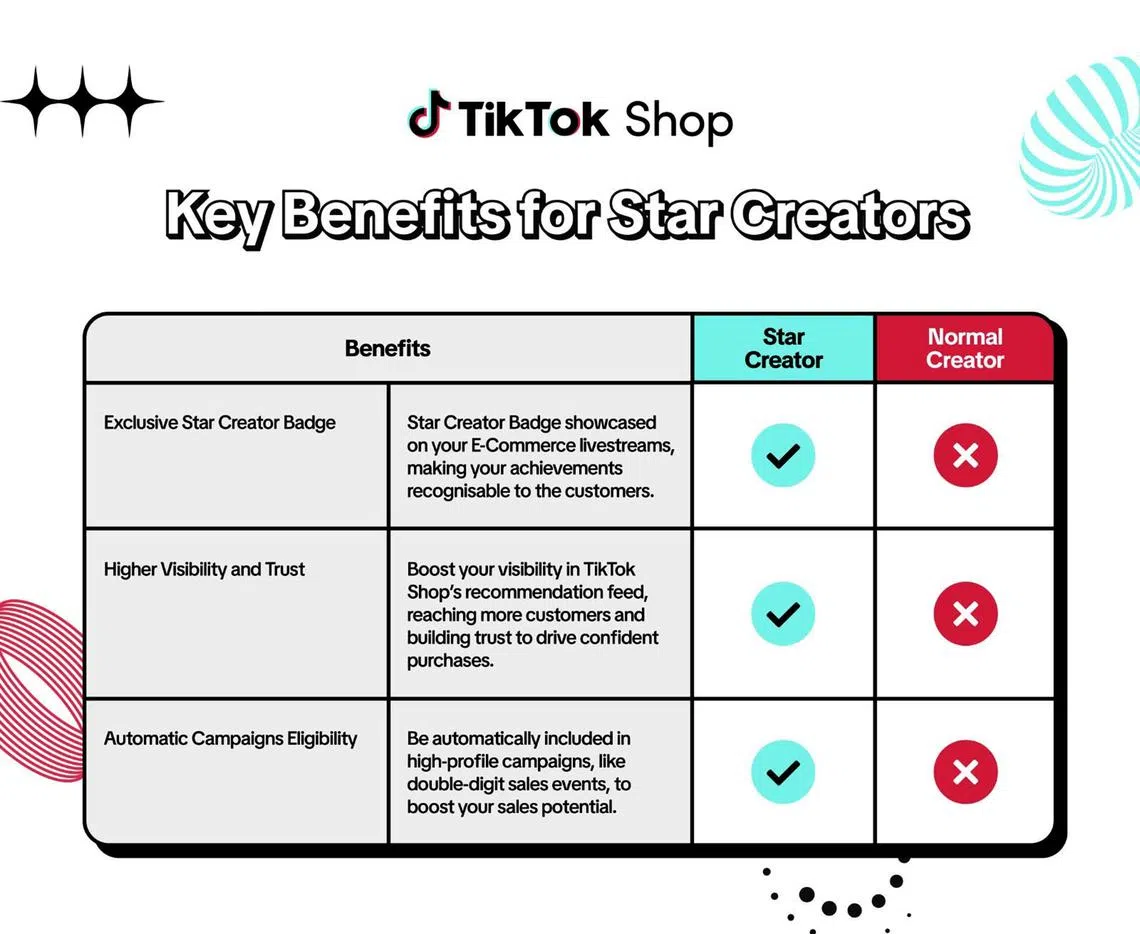

In Malaysia, TikTok has rolled out initiatives such as “star creator badges” for top live sellers and 30-day free returns for its TikTok Shop Mall products, and begun piloting next-day delivery in several locations. At its July TikTok Shop Summit, the company announced that it now gets more than 100 million product searches every day in Malaysia.

In Singapore, where TikTok has more than 3.6 million users aged 18 and up, the company has also thrown its full weight behind expanding its social shopping ecosystem here.

Long-time content creators tell The Straits Times that there was a time when social shopping in Singapore was a wilder frontier, divided between Facebook, TikTok and e-commerce players such as Shopee and Lazada.

By 2025, three years after TikTok Shop launched here, the company had created a walled garden and a network of more than 6,000 creators that has vastly outpaced its competitors.

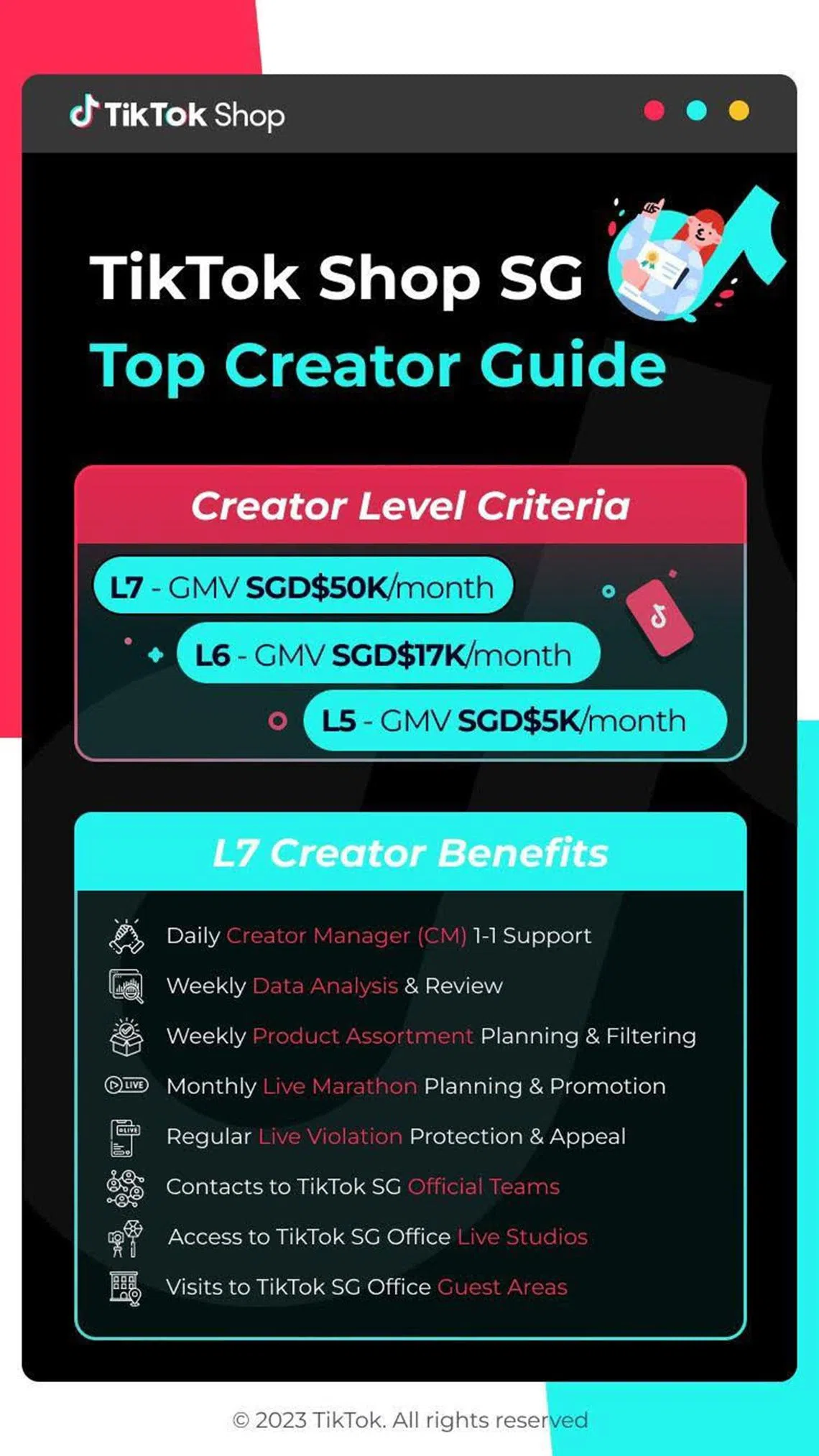

It is a game-like world for its content creators, who level up based on their sales performance.

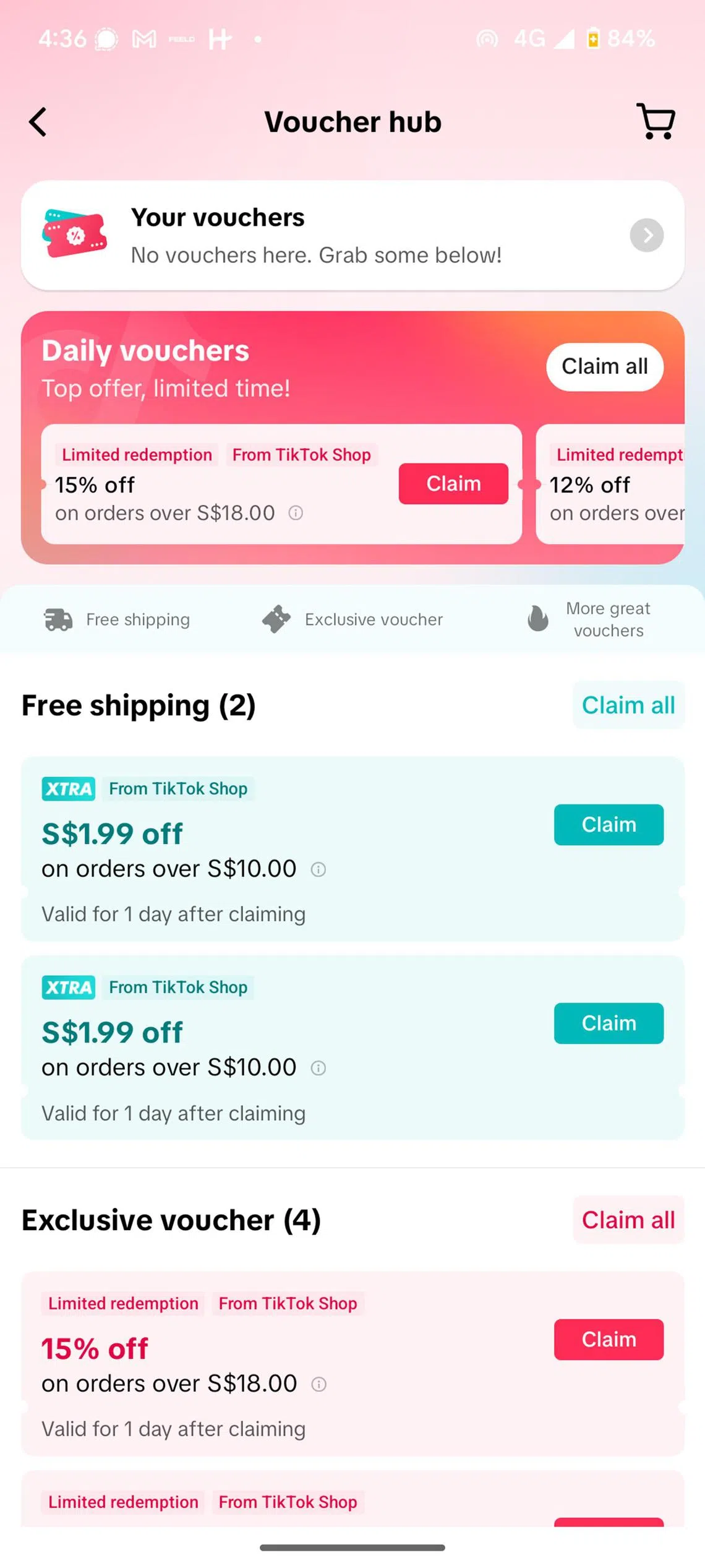

Marketing material sent to TikTok creators.

PHOTO: TIKTOK USER

These levels unlock higher visibility on the platform, star creator badges, access to TikTok’s studios and staff for extra support and, most crucially, deeper discounts for their viewers.

As part of an invite-only creator incentive, creators received a limited quantity of $4 off $33 spent vouchers for customers and a traffic boost if they met sales targets.

“It’s a direct reward system, that’s why I feel addicted,” says Mr Lim, referring to the creator benefits and the fact that payouts arrive every seven days, now that TikTok has cut out the middlemen. “I don’t have to wait three months without knowing if they’ll pay me.”

Marketing material sent to TikTok creators.

PHOTO: TIKTOK USER

One document sent to top creators in June showed that TikTok had at least 50 account managers, who liaise between creators and more than 1,000 external brands selling their products on TikTok Shop.

And the company is not done expanding yet. Mr Leon Koh, fashion and seller management lead at TikTok Shop Singapore, says the company’s TikTok Shop Live Host Academy programme aims to train 400 live-selling hosts in Singapore by the end of 2025. So far, it has trained 220.

For creators, TikTok Shop’s growth has meant that many now find live selling to be more lucrative than their former corporate gigs.

For former UX designer Feliza Toh, live selling has meant a double or triple pay bump from what she previously made in her office job.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF FELIZA TOH

Ms Feliza Toh, 27, a former TikTok UX designer, found that live selling meant a double or triple pay bump from what she previously made in her office job.

“I didn’t want to spend the majority of my life tied down to my desk,” she says, adding that the new job provides more flexibility with time and more holidays.

Meanwhile, Ms Mavis Soon, a 28-year-old full-time content creator who primarily works with beauty and fashion brands, left her software developer job in 2024. She now splits her time between live selling and creating sponsored content as part of collaborations with brands.

The unstable nature of this work has meant earnings can vary between $4,000 and $9,000 from month to month, but is still a step up from her old pay cheque.

Why so addictive?

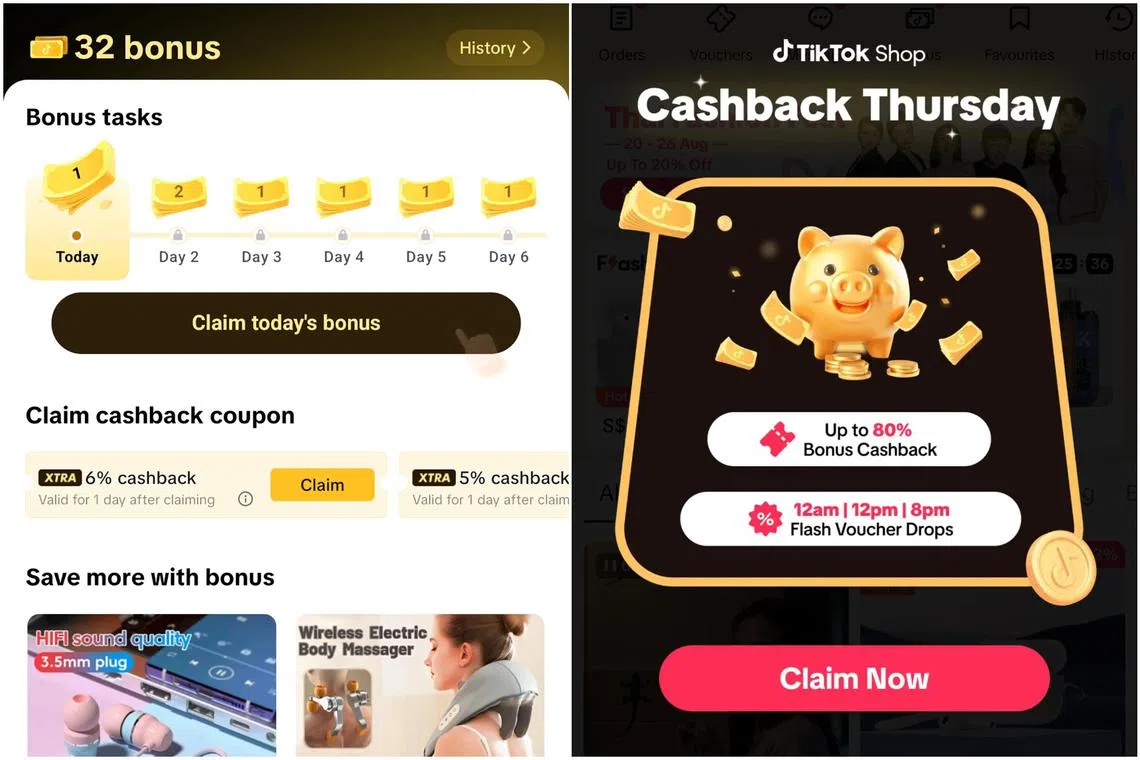

TikTok’s timed discounts and gamified features create a fear of missing out, say experts.

PHOTOS: SCREENGRABS FROM TIKTOK

The platform’s stickiness does not just affect creators, but also customers.

The app’s interface works to reduce the friction between being intrigued by a product and making a purchase, notes Dr Kokil Jaidka, an associate professor at NUS’ department of communications and new media.

“From a design perspective, it’s all about keeping the gap between ‘I want this’ and ‘I bought it’ as small as possible – sometimes under a minute,” she says.

A host of platform features and marketing strategies come into play.

Promotions occur not only during festive periods, but also as part of sales early in the month (Jan 1, Feb 2 and so on) and later in the month as payday sales.

Research assistant Insyirah Mujtahid, who studies online behaviour with Dr Jaidka, says: “Watching products sell out, hearing the seller ring a bell and announce that an item has been ‘sold out’, offering gifts to buyers and packing orders live while promising immediate shipping – all of this adds to the temptation to purchase.”

Vouchers, temporary discounts, stock counts that update in real-time and tick towards zero, and live-stream giveaways create a sense of urgency – and a rush that can be hard to replicate elsewhere.

Collectively, these come together to create a “fear of missing out” or “kiasu feeling”, which condition users to habitually return to TikTok Shop in search of a good deal.

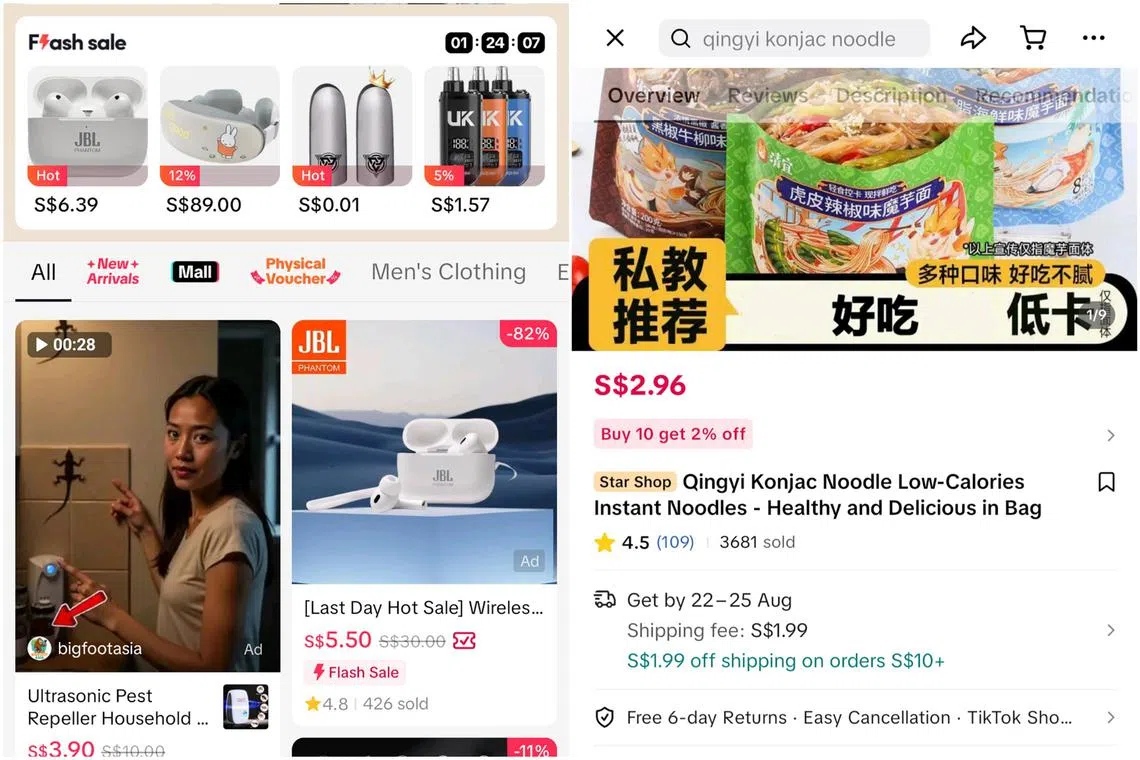

Product listings on TikTok Shop are light on details, but heavy on deals and discounts.

PHOTOS: SCREENGRABS FROM TIKTOK

Add to that the dominance of TikTok in Singapore’s social media landscape, and one finds a sales pitch that is hard to resist, say many customers.

The seamlessness of buying on the platform, coupled with the prevalence of content hawking deals, fuel their decision to buy impulsively.

“The algorithm is super annoying,” says Mr Aaron Goh, a 26-year-old civil servant and repeat buyer of perfumes on TikTok Shop. “Once you click on a product link in a video, they will just continuously feed you similar products.”

Meanwhile, Ms Champa Ha, a 35-year-old marketing professional, says she made her first purchase on TikTok Shop – sanitary pads from local start-up Blood – after seeing an introductory promotion for $2 a pack, which beat supermarket prices.

“I was sceptical at first. Was the product legit?” she says, noting that TikTok’s host of “random stuff” on offer can at times feel jarring. She is happy with the purchase, however, which arrived at her doorstep two days later.

Discounts from the core of TikTok’s appeal to both consumers and creators selling on the platform.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM TIKTOK

Money without fame

Unlike traditional influencer marketing on Instagram and YouTube, there is less of an emphasis on a creator’s story and personal brand, something which comes down to the algorithm prioritising posts over persona, says Dr Crystal.

On Instagram, beauty influencers might share why they have made the shift from a product they used to recommend, saying their hormones or circumstances have changed.

“They take you through a life course narrative to show it’s not that they are contradicting themselves or just promoting brands based on whoever pays them,” Dr Crystal explains.

“The most important thing with influencer commerce is that transparency takes you through all the turns and decisions they’ve made.”

In contrast, there is much less emphasis on personal branding and consistency for TikTok’s creators. For them, the product and one’s ability to capture attention quickly are paramount.

Ms Mavis Soon says success on TikTok Shop is more about relatability and being engaging, rather than curating one’s personality and personal branding.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF MAVIS SOON

“If I started talking about my story, people will divert their attention and not focus on the product,” says Ms Soon. “I do talk about myself once in a while, but not too much.”

Relatability is key, but not necessarily in terms of one’s persona. “I’m not that skinny,” she says. “So, when they see someone who is a medium, or if I can fit into a large, those people would watch me because they know that if I can fit, they can fit too.”

Ms Toh, who says many brands on the platform have a consistent schedule of daily live streams and a rotating cast of streamers, adds: “People don’t really care about you as an individual. They care more about the items you’re selling.

“The people who are buying want to buy the product at a good price.”

And unlike YouTube and Instagram, those who come by a TikTok creator’s content are less likely to be recurring viewers because of the nature of its algorithmic feed. These viewers are also less likely to follow them to another platform or scrutinise their claims as long-time fans.

These traits come together to create what might seem like an unusual combination: people who are making influencer-level money, but without that level of fame and celebrity. Most TikTok live sellers have followings that number in the four figures.

To Dr Crystal, these differences mean that users looking for more information about products on TikTok are at a disadvantage.

While sleuthing by users does take place on other platforms such as Reddit, where posts sometimes debunk claims made by certain creators, it takes effort for someone who wants to verify the information to go hunting for it, says Dr Crystal.

The frictionless experience of TikTok means that if information is not in the captions or comments, and the user has to make a purchase there and then, he or she is unlikely to take any external data points into account, even when such information is available.

There is also a limited variety of other listings of the same product or detailed product information, especially when compared with other e-commerce platforms.

“Because there’s no time to pause, deliberate, compare and contrast, as you might through the regular e-commerce experience, in which you open multiple tabs of the same item, compare sizes and compare colours,” Dr Crystal says. “Here, it’s just a quick purchasing decision.”

Why such weird products?

Products on TikTok benefit from an unusually visual marketing pitch.

PHOTOS: SCREENGRABS FROM TIKTOK

As many come on TikTok without the intent to buy anything specific, products that do well are typically visually pleasing, solve problems that users might not know they have or offer novelty.

A standard skincare product that can be found easily at chain retailer Watsons or e-commerce alternatives can be a tough sell, especially since such products are not always cheaper on TikTok Shop without stacking discounts.

Instead, businesses with the most to gain are those which import goods not easily found at local retailers, have products that require explanation or are still trying to break into the mainstream.

Konjac noodles, for instance, are frequently marketed in affiliate marketing posts by creators on TikTok, and typically accompanied by explanations on how its low-calorie content makes it an ideal low-cost snack for those seeking to lose weight.

Beyond niche goods, the platform has also onboarded mainstream brands such as Dyson, Samsung and Medicube, with creator-made videos that involve demonstrations and experiences with the products.

Mr Jotham Lim during a live stream conducted in Seoul.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF JOTHAM LIM

Creators say that something that adds to their sales pitch is brand-facilitated trips to shops in China, Vietnam or South Korea, where they live-stream on-site.

“If I’m selling a Korean product from South Korea, viewers will feel it’s authentic, it’s safe to buy,” says Ms Soon. “Since I can’t travel to South Korea, I can just buy it from you.”

Selling out fast

The founders behind local start-up Matcha Masta say TikTok Shop is ideal for small businesses looking to break into the mainstream.

PHOTO: MATCHA MASTA

To Ms Tiara Hudyana, co-founder of local start-up Matcha Masta, TikTok Shop is now the top platform for customers to discover new brands, especially for Gen Zs and millennials.

She first listed her green tea offerings on the platform in November 2024,

“It’s the best way for businesses, especially small ones, to get in touch with new audiences and customers,” she says.

For one thing, the start-up costs of getting on TikTok are low. Unlike pop-up events that require booth building, rent and manpower costs, one typically needs only a table, good lighting and a microphone to start making videos.

Ms Tiara began conducting live streams through TikTok in July, selling matcha powder that costs upwards of $48 for 40g. These two-hour live streams are hosted by co-founders and matcha enthusiast creators alike, with “Will it matcha” taste tests, and pairing the product with other dishes.

“With TikTok Live, you’re able to showcase how you make the matcha, the beautiful bright green colour and see it in action, versus showing the product in an almost one-dimensional way,” she says, referring to static posts and product listings.

Local start-up MadeToBloom’s founders say TikTok’s interactive nature means being able to sell product while sharing practical haircare tips and product demonstrations.

PHOTO: MADETOBLOOM

Live selling is key, says the team behind MadeToBloom, a local halal-certified hair and bodycare start-up. Since the company started live selling, it has seen a fivefold increase in sales on TikTok.

Meanwhile, sisters Grace Lim, 33, and Lena Lim, 29, co-founders of local home-based bodycare business Emporal Co, say TikTok Shop helped turn their business around after a two-month period of zero orders.

Since getting on the platform in 2024, they have sold more than 11,000 bottles of leave-in conditioner ($25.90 each) and 9,000 bottles of body wash ($24.90 each).

“On other platforms, you can’t purchase from a video,” says Ms Grace Lim. “The impulse is there.”

Future (past) of shopping

For all of its bells and whistles, part of what makes TikTok Shop so successful is also how it resurrects a dying medium – or two.

Sisters Grace (left) and Lena Lim (right) have garnered more than 100,000 followers through their TikTok account.

PHOTO: EMPORAL CO

These are the shopper-tainment TV channels and live demonstrations at department stores of old – both sales channels where anecdotes, personal testimonial and fast-talking showmanship are key elements of a business’ sales pitch.

The focus on anecdotal benefits can absolve businesses of responsibility when their products do not work, says Dr Crystal. After all, “it worked for me” is not a claim that it will work for others too.

Dr Crystal notes that in her years of researching and following creators, many would argue that their hyperbolic claims are no different than the banners and pop-ups that attract one’s attention when walking through a store.

“It may say zero sugar, but when you read the back of the can, it’s really ‘zero sugar added’ and there’s natural sugar in the fruit,” she says.

“The ethical issues here are not specific to TikTok or live shopping. It’s blanket across the advertising industry, where there are a lot of caveats.”

The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore’s (Asas) code of advertising practice calls for advertisements to be legal, decent, honest and truthful.

Its guidelines state that misleading claims should be avoided, and testimonials must be genuine and representative experiences. Content creators must also disclose their commercial relationship with their clients.

From 2022 to July 2025, Asas received six pieces of feedback related to TikTok Shop. It also received two on live selling on other platforms in 2025. The most common issue was misleading claims about the product and terms of sale.

If disputes arise, the Consumers Association of Singapore’s (Case) dispute management framework for e-marketplaces requires these marketplaces to verify the identity of merchants, establish mechanisms for consumers to assess their reliability and resolve customer complaints within a reasonable timeframe.

Content creator Feliza Toh believes that the platform allows for raw and unfiltered interactions with one’s audience that make for a more authentic sales pitch.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF FELIZA TOH

However, creators like Ms Toh think that TikTok viewers are aware that those hawking the goods are not themselves responsible for the quality of the product eventually received.

“Everyone has an understanding that as a live streamer, you’re a third party,” says Ms Toh. She recalls an instance when she helped to solicit an apology from a skincare brand she worked with over customer complaints.

“It’s kind of like a tag team, where we have to work with the sellers.”

The new celebrity

Live seller Jotham Lim is one of Singapore’s best-performing TikTok live sellers.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

One of the most striking features of social shopping is how it represents a fundamental shift in the way content creators are engaging with social platforms. Instead of becoming brands and celebrities in themselves, these are salespeople and businesses first.

Emporal Co’s co-founder Grace Lim says TikTok has meant being recognised in public by her customers. One even asked for a selfie together because she had supported the brand for years.

When selecting creators to sell her goods, Ms Lim says she looks out for someone who can entice her to buy a product. “If it converts me, it will convert other people.”

Even the way that creators build authority and credibility with their viewers differs from the influencers of old, who sought to cultivate an aspirational brand and lifestyle.

Today’s live streamers cultivate a reputation for knowing a good deal or weaving their personal anecdotes, say, of hair loss or an interest in K-pop into why one should buy from them.

“What I’ve realised about my journey is that it’s all about the money that’s brought in. There’s no, ‘Oh, Jo, I like you because of your personality.’ It’s all about the money,” says Mr Lim.

“It’s like merging a salesperson with an influencer. It’s the perfect marriage. That’s why brands love us more than Instagram stories or reels now.”