This is what ADHD looks like – from buying multiple earplugs to getting diagnosed because of your kids

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

(Clockwise from top left) Mr Ahmad Nizam Abbas, Mr Esmond Wee, Mr Wong Siew Hong, Ms Tahirah Mohamed and Ms Winnie Wong are among the over 60 people featured in a new book about differently wired minds.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

SINGAPORE – For father-of-four Esmond Wee, 44, living with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) means buying five pairs of earplugs – because he keeps misplacing them – to ease sensory overload.

Such sensitivity to noise and distraction is one common thread among those with ADHD, a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity that interferes with daily functioning.

Overstimulation in contexts that others might find tolerable perhaps explains why many with ADHD do their best work in the early hours.

Partly for the tranquillity, but also because that is often when procrastination guilt from executive dysfunction – another common ADHD symptom – finally boils over into action as deadlines loom.

Mr Wee’s quest for solace is made all the more complicated by raising four children aged three to 18, the eldest of whom also has ADHD.

“If you notice your kid has to check out, that’s a major sign he or she is dealing with sensory overload,” says the marketing professional and music label co-founder, who got diagnosed with the condition in 2018. “For our daughter, it’s very obvious, she needs to decompress by locking herself in her room.”

Yet, it is his wife, freelance writer Sue-Ann Lee, 50, who shoulders the heaviest burden. “She’s keenly aware that I have ADHD and that I need to excuse myself because, sometimes, the sensory overload is too much and I will explode in front of the kids,” he says.

For the couple, clear communication is essential. Mr Wee compensates by taking on extra chores and whisking the children out of the house when his wife needs downtime.

“My kids see my inability to handle the sensory bit, but that in a sense brings us closer together,” he says, adding that apologies and open discussions about feelings are teachable moments in the household.

Mr Esmond Wee and Ms Sue-Ann Lee with their children (from left) Elijah, 15; Scarlett, three; Ezekiel, 10; and Skyler, 18.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ESMOND WEE

Their family is one of many living with ADHD, the most common neurodivergent disorder in Singapore. It is said to affect 5 to 8 per cent of children and 2 to 7 per cent of adults here.

Mr Wee and 63 others share lessons learnt from a lifetime with the condition in a book by non-profit organisation Unlocking ADHD titled Differently Wired Minds, published as part of ADHD Awareness Month in October.

According to the Ministry of Health, between 2021 and 2024, about 1,200 patients diagnosed with ADHD

And yet, this is a group often misunderstood because of outmoded attitudes towards mental health.

Experts say that despite growing public awareness, misconceptions remain.

“Many people still view ADHD as a childhood phase that will be outgrown or assume it results from inadequate parenting,” says Dr Chee Tji Tjian, a senior consultant at National University Hospital’s (NUH) department of psychological medicine.

This is compounded by stigma and beliefs that medications are harmful, says Dr Gangaram Poornima, a senior consultant at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH).

The consequence is that many perceive those with ADHD as lazy, careless or defiant, leading to many emotional scars for those who grow up with it.

Children are frequently criticised for behaviours they cannot control and experience an erosion of self-confidence and self-worth. They can come to internalise harmful labels and beliefs that they are inadequate, says Dr Chee.

Instead, normalising conversations about mental health and celebrating different cognitive styles – coupled with early recognition and support – can help those with ADHD to harness their strengths and lead fulfilling lives, he adds.

People who do too much

Mr Wong Siew Hong says that fixating on seemingly unimportant details is his ADHD “superpower”.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

For lawyer Wong Siew Hong, 63, one early case stands out when processing the impact of ADHD on his life. He got diagnosed with the condition at age 43, when things were “falling apart” as he contemplated divorce and struggled with suicidal ideation.

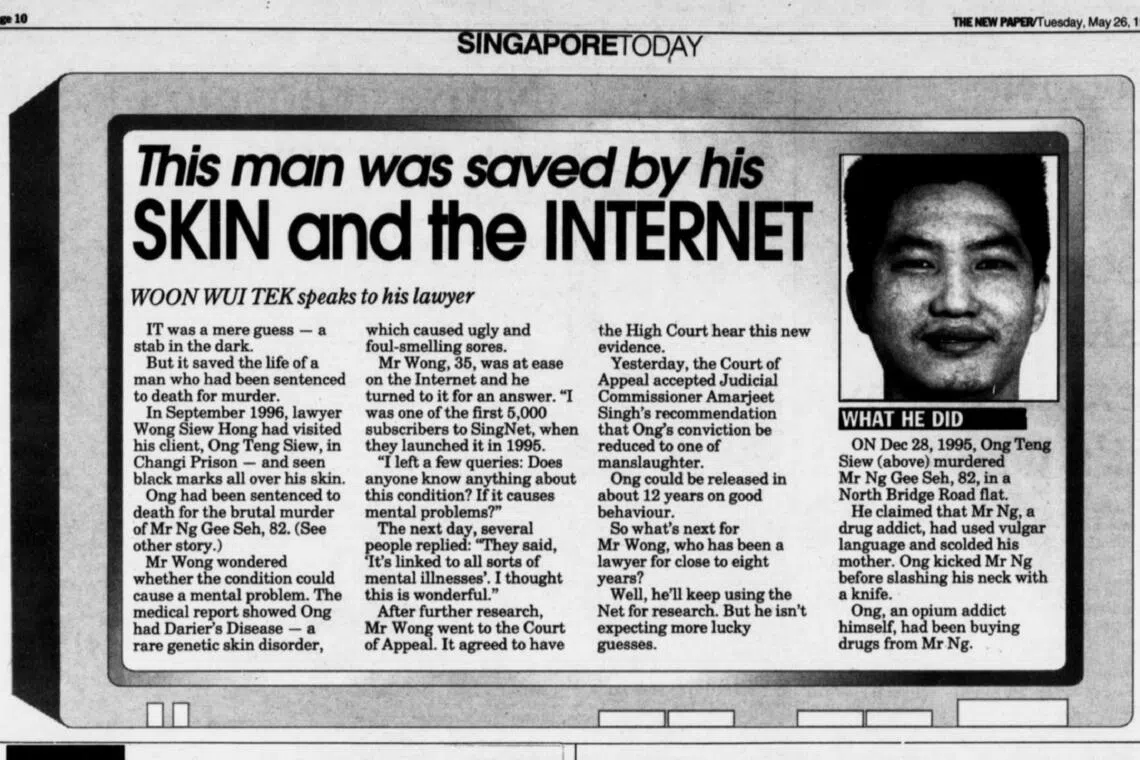

In 1996, Mr Wong was defending Malaysian national Ong Teng Siew, who was convicted of murdering an 82-year-old man and sentenced to death. After the trial, his client developed what appeared to be shingles and was diagnosed with Darier’s disease – a rare genetic skin condition affecting one in three million.

Mr Wong, who describes himself as endlessly prone to distraction and fixating on details that might seem pointless at first glance, thought this was a rabbit hole worth diving into.

Back then, he was among the first subscribers to SingNet, one of Singapore’s early internet services. Trawling through online medical discussion groups, he found a connection between Darier’s disease and psychiatric disorders.

A 1998 report in The New Paper about lawyer Wong Siew Hong’s case. His client’s life was spared because his fixation on details led him to zero in on a pivotal one.

PHOTO: ST FILE

By arguing that the condition could establish diminished responsibility, Mr Wong convinced the Court of Appeal to order a retrial. That eventually spared his client’s life.

Such out-of-the-box thinking and the relentless pursuit of seemingly irrelevant details represent what Mr Wong, who is now divorced, considers an ADHD “superpower” – even as he continues to struggle with executive dysfunction and motivating himself to complete routine tasks.

“I will never be able to do conveyancing, for example,” he says, referring to the legal process of transferring ownership of a property. “It’s too much routine work and my eyes glaze over. I like to look at things from another angle, another point of view.

“That’s not necessarily a good thing, but it’s served its purpose in a few situations in my life.”

Ms Winnie Wong, a kintsugi artist and life coach, believes that people with ADHD often wind up becoming multi-hyphenates as they seek to marry their passions and professions.

PHOTO: SILK AND SALT IMAGES

Also featured in the book is Ms Winnie Wong, 32, who believes there is some truth behind the stereotype that people with the condition tend to be more fickle-minded, especially about their careers. This is because wrestling with executive dysfunction often leads to burnout and career pivots towards passions or pursuits better suited to one’s neurodivergence.

Like many interviewed by The Straits Times, her career defies easy description. She is a multi-hyphenate – a life coach and an artist specialising in kintsugi (the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery) who is also training to be a death doula, to provide support for those who are dying.

“Growing up in a very Asian household, you’re always told to focus on one thing and do it well,” says the former advertising and art director. “I thought I had to continue pursuing this path, but I fell into depression and was fired from my agency. That forced me to find a creative outlet so I could heal from it.”

Now, her approach is “throwing all the spaghetti at the wall and seeing what sticks”, without being too stuck on the idea that people have to limit themselves to one thing. “You can mix mediums,” says the communications graduate, who has also worked as a prop stylist and a freelance designer. “You can create a very ‘niche niche’ for yourself.”

Another key lesson is learning to be kinder to oneself.

“The time you think you’re procrastinating, you’re actually marinating the things you want to do,” says Ms Wong, who was diagnosed with ADHD at age 31. “Something is happening, you just don’t see it yet. Just let it marinate. You’ll be able to churn it out.”

ADHD and ageing

Ms Tahirah Mohamed began considering that she might have ADHD only after two of her children were diagnosed with it.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

While ADHD might often seem like a young person’s challenge, many older adults are discovering that their lifelong struggles have a name.

Ms Tahirah Mohamed, 48, had her life-altering diagnosis only in her 40s.

The revelation came after two of her nine children, aged six to 24, were diagnosed with ADHD. Given the condition’s high heritability, parents and children often share the diagnosis. Ms Tahirah merely assumed that her kids had “inherited my creativity”.

Her experience is not uncommon in the ADHD sphere. For many parents, like Unlocking ADHD founder Moonlake Lee and Mr Wee, seeing the symptoms in their children was part of what inspired them to seek a diagnosis for themselves.

Ms Tahirah Mohamed (seen at age three) has shown signs of ADHD since her childhood, but sought a diagnosis only after becoming a mother.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF TAHIRAH MOHAMED

Looking back, Ms Tahirah realises the clues were obvious. She recalls school days when she would be called out by teachers for daydreaming too much, and having to rely on friends to figure out what homework had been assigned.

Over the years, the housewife’s coping strategies have included relying on colour-coded calendars and phone alarms, and using “brain dumps” – writing everything down to organise her thoughts.

Finding support groups is also key, as those with ADHD are often surrounded by peers who do not understand their struggles.

“I created a system for myself that worked until recently, because I’m 48 and experiencing perimenopause,” she says, adding that she is more forgetful now and finds the responsibilities that come with raising a big family trickier to juggle. “Perimenopause heightens the struggles I’ve been facing all these years.”

She adds: “I believe that might be the reason some women with ADHD are diagnosed late in their 40s and 50s.”

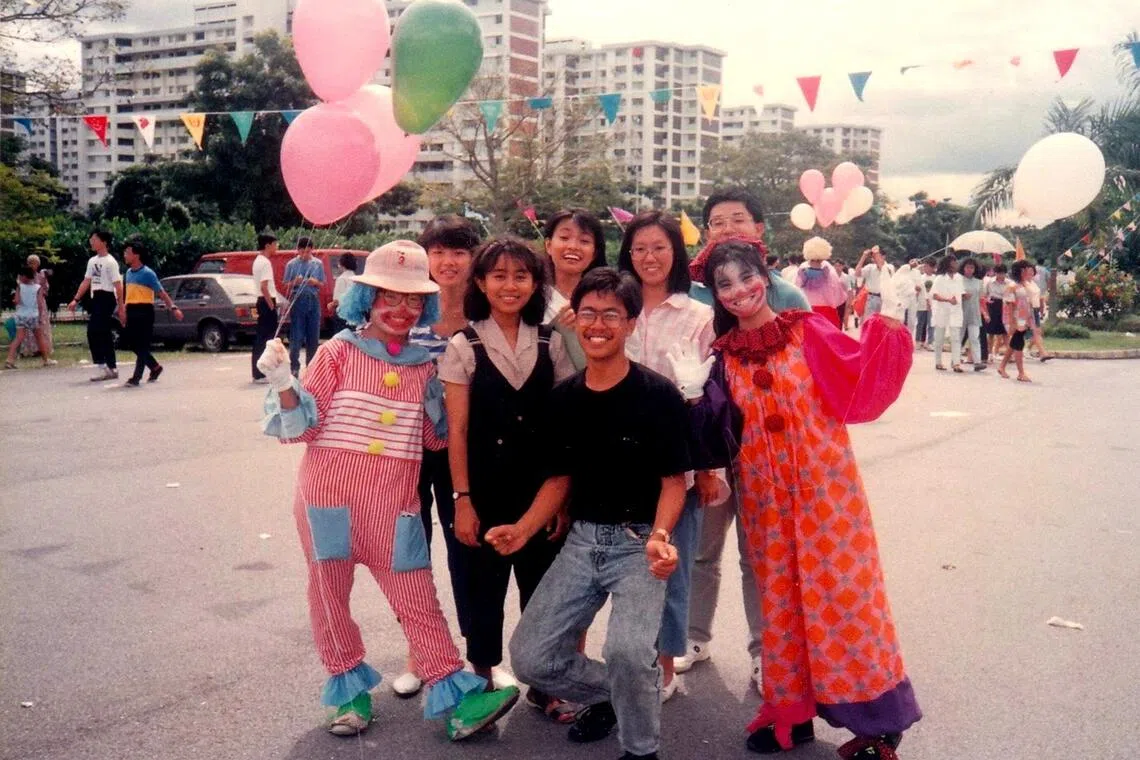

Mr Ahmad Nizam Abbas (front) as a junior college student at age 18.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF AHMAD NIZAM ABBAS

Similarly, lawyer Ahmad Nizam Abbas, 58, also came to his diagnosis later in life.

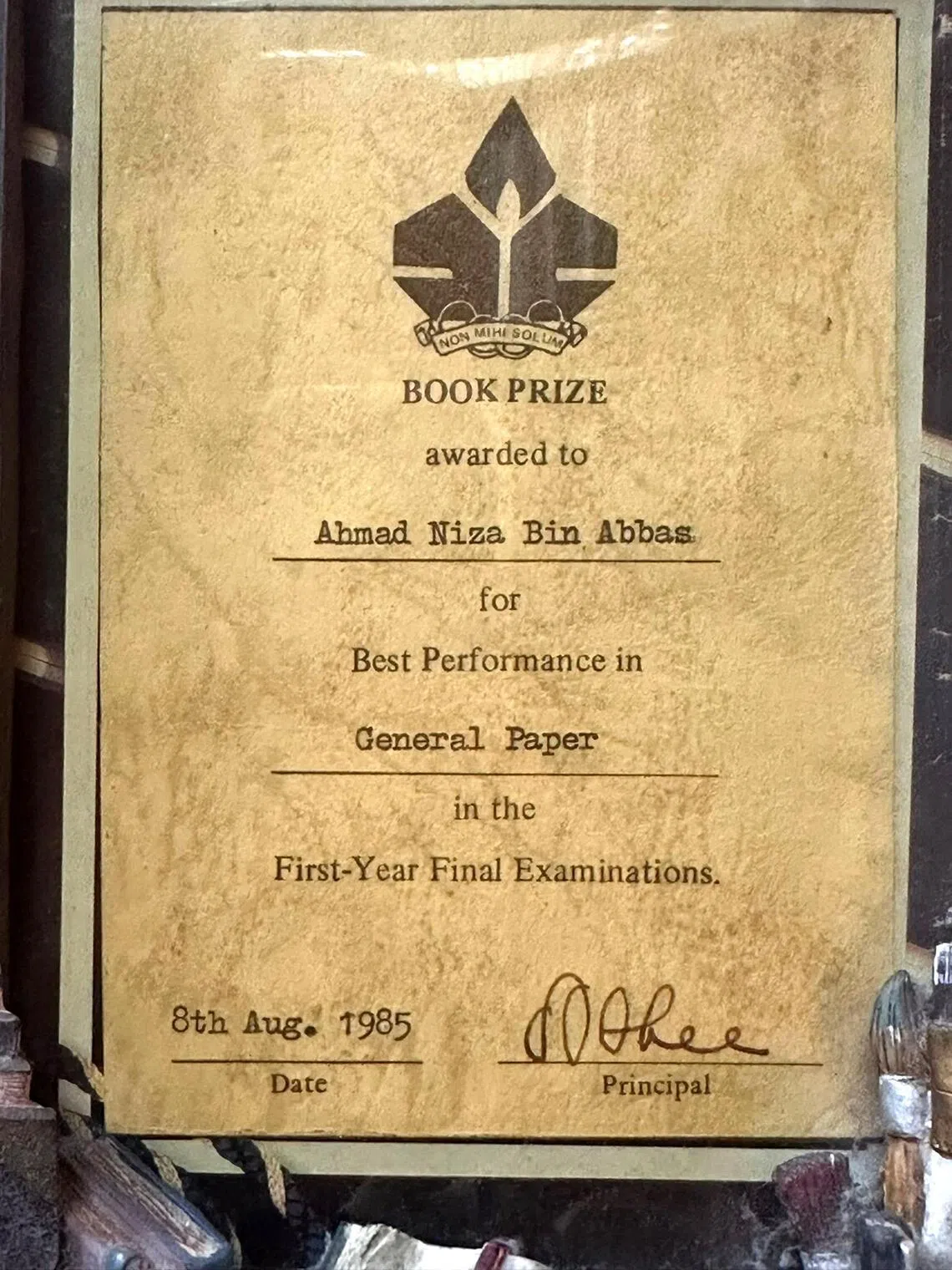

Hindsight, too, reveals the early indicators. “My school results were like a see-saw,” he says.

Even though he had excellent grades in some subjects, to the point that classmates would crack jokes that he was a “walking encyclopaedia”, he would often fall asleep in classes he was disinterested in.

He looks back on his formative years with wistfulness. The family lawyer wishes he could have sought advice earlier, or applied coping techniques he spent a lifetime devising for himself.

These include figuring out how to make learning more interesting through unconventional modes like podcasts and YouTube videos, and pushing himself to go beyond his interests.

Mr Ahmad Nizam Abbas says his report cards were a mix of top marks and low grades.

PHOTO: AHMAD NIZAM ABBAS

Still, that tendency to fixate remains one he is thankful for.

“My superpower is going into the zone,” he says. “If I have to do a submission for one of my cases, I shut myself off from the rest of the world.”

Everyone in his office knows he is not to be disturbed and will not take calls or have meals when on a case. “I just cannot be distracted and I lose track of time,” he says. “It can go on for hours, but at the end of it, I look back on my work and I’m proud of it – even though I’m exhausted.”

Experts note that even though ADHD is genetic and most people are diagnosed during childhood, many receive diagnoses later in life because of the various ways it can escape detection.

Some who present primarily symptoms of inattentiveness are often dismissed as “daydreamers” or “shy”. Others develop coping strategies that might work during childhood, but give way when the multi-pronged demands of life intensify during adulthood.

“Most of them have suffered in silence due to a lack of awareness or social stigma,” says Dr Poornima.

Gender, too, plays a role, as girls tend to have “inattentive” symptoms that present less obviously than those of hyperactive boys, which remain the stereotypical image many associate with ADHD.

A late-in-life diagnosis helps one to understand and contextualise lifelong challenges, and often comes with a sense of relief or validation, says Dr Chee.

However, it can also evoke profound grief over lost opportunities or unrealised potential. “Many adults mourn careers that stalled due to disorganisation, relationships that suffered from emotional dysregulation or decades spent believing they were lazy or incapable,” he observes.

A lifespan condition

In Differently Wired Minds, a new book from the non-profit Unlocking ADHD, those living with ADHD share candidly about how the condition has shaped their lives.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

But the good news is there may not be a better time to be diagnosed than today.

“Compared with the 1990s, when ADHD was largely unknown to the masses or ADHD symptoms were predominantly viewed as a behavioural problem requiring discipline, today, it is increasingly recognised as a legitimate neurodevelopmental condition affecting attention, executive functioning and emotional regulation,” says Dr Chee.

In his view, this paradigm shift has enabled teachers, parents and healthcare providers to identify symptoms earlier, as well as move away from punitive approaches towards more empathetic support strategies.

NUH data indicates that adult diagnoses are increasing as awareness grows, indicating that ADHD is a “lifespan condition” requiring sustained attention from healthcare providers and not merely a “childhood phase”, says Dr Chee.

In 2023, NUH diagnosed 515 patients under 21 and 176 adults with ADHD, out of over 884 youth and 2,600 adults assessed.

Although awareness of ADHD has improved by leaps and bounds, its new visibility can be a double-edged sword.

Dr Chee notes a growing trend of people mistakenly identifying normal variations in attention or energy as ADHD. For example, some parents seek assessments for young children displaying age-appropriate levels of restlessness. Other adolescents and adults pursue a diagnosis to explain struggles that result from other causes, such as stress, sleep deprivation or mood disorders.

“As public awareness continues to mature, the challenge lies in promoting a balanced understanding,” he says.

This means recognising ADHD where it genuinely exists, while avoiding over-pathologising normal differences in behaviour.

For Ms Lee, who founded Unlocking ADHD in 2021, the progress made in recent years is heartening to see, as it means more discussions about what support should look like at schools and workplaces.

Unlocking ADHD has partnered multinational conglomerate Jardine Matheson to launch Singapore’s first ADHD-focused facility, the Unlocking ADHD-Mindset Support Hub in Holland Drive. The company’s $1 million pledged over three years will enable the hub to support over 100 people annually with more than 1,000 hours of ADHD-tailored counselling services.

“ADHD is often misunderstood, and many individuals fall through the cracks due to stigma, delayed diagnoses and a lack of structured support,” says Mr Jeffery Tan, chief executive of Mindset, a charity initiative from Jardine Matheson. “Through this partnership, we aim to close those gaps and build a safe, inclusive ecosystem where every individual can thrive.”

As to what barriers remain unaddressed, experts say policymakers can strengthen the support ecosystem by expanding access to affordable assessments and treatments in the public healthcare sector. Assessments by private psychologists can cost $2,000 or more, while an initial consultation with a private psychiatrist can cost upwards of $300.

Subsidised rates for eligible patients are available at public institutions, but may come with longer wait times for appointments. An initial consultation at IMH costs $32.86 to $80.74 with subsidies, but requires a referral from a polyclinic or Community Health Assist Scheme GP clinic.

Workplaces can consider accommodations to help neurodivergent individuals thrive by discussing flexible work arrangements, providing distraction-free environments and using effective project management software.

Parents and friends can support someone living with ADHD by showing him or her understanding and patience and giving him or her structure.

This can be as simple as recognising that forgetfulness does not always indicate a lack of care. It might just be what ADHD looks like.

Get a copy of Differently Wired Minds by donating $150 or more to Unlocking ADHD, while stocks last.