Swedish former model revives abandoned homes in Japan

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

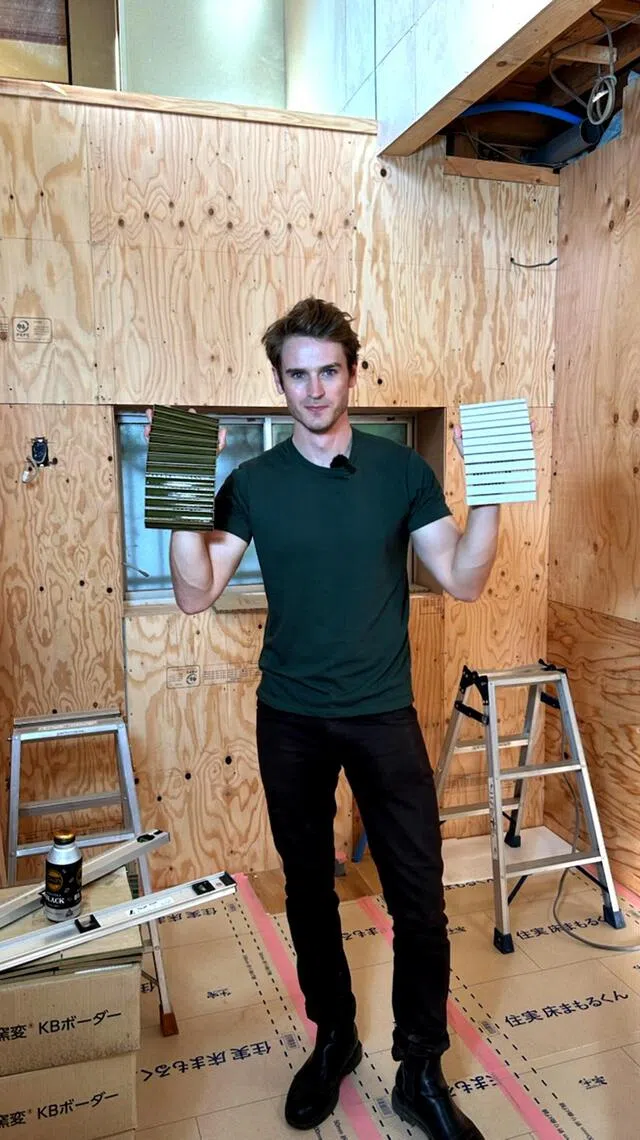

Sweden-born Anton Wormann buys and refurbishes abandoned homes in Japan.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ANTON WORMANN

A Swedish fashion model becoming a home renovation influencer in Japan might be one of the least likely career arcs imaginable.

But 32-year-old Anton Wormann has bought and refurbished several properties in Japan, doing much of the renovation work himself.

And through his popular Anton In Japan social media accounts, he has become a champion of the country’s akiya, or abandoned homes.

He got his first taste of Japan working in Tokyo as a fashion model. What began as a series of two-month modelling stints ended with him falling in love with the country and deciding, in 2018, to make it his home.

Wormann, who has modelled for Italian fashion house Gucci and American retailer Abercrombie & Fitch, tells The Straits Times in a video call: “I loved it here every time I came. It was just paradise. The streets are clean, it’s safe and every day is an adventure.”

Then he learnt about akiya, which in Japanese means “empty houses”.

As Japan’s population ages and birth rates plummet, there are fewer people inheriting, purchasing or maintaining its homes.

So, millions sit empty. According to Japanese government figures, one out of every eight homes, or nine million, lay vacant in 2023. Of these, 3.9 million are not for rent or sale, nor used as secondary residences.

Fashion model with a hammer

Handy with tools, Anton Wormann takes an intrepid DIY approach to renovation.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ANTON WORMANN

Into this vacuum have stepped foreigners such as Wormann, drawn to Japan’s property market by its comparatively low prices, the depreciating yen, and an appealing culture and quality of life – all of which have also sparked a tourism boom.

This, in turn, has been accompanied by a surge in social media content about tourism, expatriate life and Japanese property, the latter mostly from brokers.

But Wormann is not a broker, and stands apart with his focus on akiya, an intrepid do-it-yourself (DIY) approach to renovations and a fondness for Japandi design – a blend of Japanese and Scandinavian aesthetics.

He details the triumphs and struggles of his akiya makeovers on YouTube, TikTok and Instagram, where his Anton In Japan channels have more than 2.2 million followers combined.

He also has a second YouTube channel where he addresses viewers in Japanese, which he speaks proficiently.

But his journey began with a disaster.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, Japan locked down and its fashion industry ground to a halt, abruptly ending his modelling career.

Wormann found himself jobless in Tokyo and staring down Japan’s notoriously unfriendly rental market.

“They require two months of deposit, two months of real estate fees, key money, guarantor money and ‘gift money’ to the landlord,” he explains.

“You can end up paying a year’s rent up front – money you’re never going to see again.”

So, instead of renting, he decided to buy – and for just US$95,000 (S$123,500), acquired a rundown apartment close to Shibuya in the heart of Tokyo.

“I paid in cash, and it was basically all the money I had at the time. But my fees for buying it were cheaper than renting the equivalent.”

He then set about renovating it himself using the basic carpentry and other skills he had learnt growing up in Sweden, where there is a strong DIY home-renovation culture.

Anton Wormann learnt carpentry and other skills in Sweden, so he can do his own renovation work.

PHOTO: ANTON WORMANN

His childhood home, built in the early 1900s, required constant repairs and tweaks which his parents, like many Swedes, undertook themselves.

Learning from them, he and his two sisters built a two-storey treehouse in their younger days.

“During our summer holidays, we’d always have a DIY project – repaint something, rebuild something.

“In Swedish schools, we also have three hours a week of woodworking from age nine.”

The Swedish school system has taught woodworking and textiles as a compulsory subject since the 1950s. Wormann believes two world-famous Swedish brands – furnishing retailer Ikea and clothing company H&M – “probably came out of that”.

So, tackling home renovations yourself “is how Swedes think the rest of the world works too”.

No DIY culture in Japan

That said, renovating his first Tokyo home did not go smoothly.

“I had no idea where to buy materials,” he recalls. “All of my friends were in the fashion industry and I knew nothing, so I went to Hands, which is more like an art supply store. I didn’t even know where the closest home-improvement centres were.

“I made so many mistakes, but it became a really cute apartment that has been featured in many magazines,” he says of the property, which has been visited by Caleb Simpson, an American influencer known for asking strangers for tours of their New York City homes.

Wormann has since moved out of that flat, which he dubs the Tree House, and rents it to a friend on a long-term basis (the tour she gave Simpson went viral on YouTube

Although Wormann still does a bit of modelling on the side for Japanese brands, appearing in the occasional television commercial or catalogue, refurbishing akiya has become a full-blown obsession. He owns seven properties, most of them in Tokyo.

Five are rented out for short-term stays that can be booked at japandihouses.com

Renovated in a Japanese-Scandinavian style, these tranquil spaces blend the hallmarks of Swedish design – simplicity, minimalism, a neutral palette, natural materials such as wood and plenty of natural light – with iconic Japanese elements such as tatami floors and shoji sliding doors.

In his social media posts, Wormann also enthuses over details less well known outside Japan, including traditional joinery techniques that do not use nails or glue; or yakisugi, which employs a blowtorch to char wood, making it bug- and water-resistant without chemicals.

Anton Wormann mixes his Swedish childhood with Japan’s design philosophy.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ANTON WORMANN

Explaining his design philosophy, he says: “I’m not a designer or an architect.

“I just bring my childhood from Sweden and mix it with the beautiful Japanese details that are already in front of me.”

And with each property, he has applied the same DIY renovation approach, which is surprisingly rare in Japan.

“The way Japan is portrayed abroad, when you think of a Japanese house, you think of an old, beautiful house, almost like a temple, and you think of kintsugi, the Japanese technique for repairing broken pottery.

“But when I first moved to Tokyo, I didn’t see any of that. It was just brand-new builds. People were tearing down perfectly fine houses.”

That approach is anathema to Wormann.

“A new house feels unlived-in – that’s worse than a hotel room,” he says. “It needs to feel warm, it needs to have sunlight and it needs to feel thoughtful, somehow.”

He still does much of the work himself, although he has found a talented carpenter, and hires contractors for the electrical, gas and foundation work.

The list of tasks is endless, says Wormann, who is living in one property while renovating another.

“We’ve been working on it for about a year. Tomorrow, I’m doing the last trash round, then we’ll build a bamboo fence and clean.”

Thankfully, his girlfriend – a South Korean model who has lived in Japan for 15 years – has caught the DIY bug too, and has learnt to pitch in with flooring, tiling and painting.

Failure and friends

A Japanese bathtub in one of the houses renovated by Anton Wormann.

PHOTO: ANTON WORMANN

Wormann periodically rounds up a gaggle of friends, including other models, to help clear out one of his newly purchased akiya, whose previous owners often leave behind a lifetime of clutter.

And he continues to be open about his failures – posting, for instance, about how he had purchased a US$15,000 abandoned farmhouse in a rural part of Chiba prefecture, only to realise he had bitten off more than he could chew.

Wormann is something of a celebrity in Japan now, and is often interviewed on Japanese television and radio.

“The Japanese media has been a lot about, ‘Is what he’s doing the solution to the problem of abandoned houses?’

“People find it very interesting and many Japanese people are kind of copying me, which I think is great.”

The idea of foreigners buying property remains controversial, though.

“There are Japanese politicians proposing bans on foreign ownership. And when my Japanese friends think about foreigners buying in Japan, they think of Chinese investors buying to get money out of their country.

“But I’m not a broker,” Wormann adds.

“I’m living in these houses, I’m renovating them with my hands, and I’m friends with my 85-year-old neighbour and my 70-year-old neighbour. I don’t think I could have had that by just renting.”

And he firmly believes buying an akiya should not be just about an investment.

“It’s about being part of a community,” he says. “You need to contribute to receive the good things.”

Costs and caveats of buying akiya

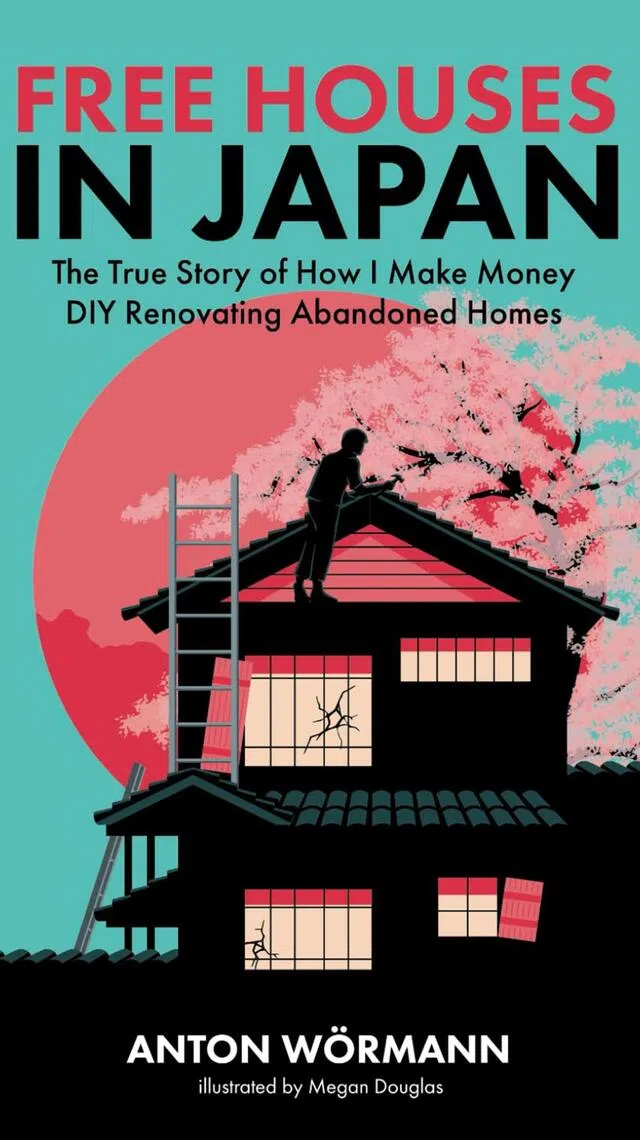

Anton Wormann has published a book detailing his experiences in revamping akiya, or Japan’s abandoned houses.

PHOTO: ANTON WORMANN

Wormann details his experience buying and renovating Japan’s abandoned houses in a 300-page book, Free Houses In Japan – The True Story Of How I Make Money DIY Renovating Abandoned Homes, published in November 2023 and available at Amazon.sg for $33.99.

For those who are serious about buying a home in Japan and want help navigating the process, he also runs a Cheap Houses In Japan online course at akiyamasterclass.com

Here are some of his top tips and caveats.

What it costs

An abandoned home, or akiya, can cost as little as US$3,000 in a Japanese city, says Wormann.

“Close friends have got houses for free. My cheapest house has been US$15,000 including the land, and it was 60 minutes from Tokyo.”

Full renovations can cost from US$20,000 to US$50,000 for a two- to three-bedroom house, “but the sky is the limit”, he adds.

Property taxes are often US$100 to US$300 a year in city areas, and insurance is optional and affordable at US$100 to US$200 a year.

No mortgage is needed, and the low cost allows outright cash purchase.

Many akiya remain vacant in cities, with even more availability in rural areas. There is minimal paperwork, with no credit checks, and the purchase can often be finalised in days.

“But you have to know how to find these deals too. They are mostly not on the open market,” he adds.

“Real estate agents are working solely on commission, or a percentage of the sales price, so no real estate agent wants to help you buy a cheap house where they’re not making any money.

“So, you’ve got to really pull your information from several different angles to find these good deals.”

Legalities

Foreigners do not need a visa or residency status to buy property in Japan.

“You can live overseas and still purchase under nearly the same conditions as Japanese citizens,” says Wormann, who reveals that half of his course participants are American, with the rest mostly from Britain, Australia and Germany.

But buying a property does not confer any residency status. Non-citizens must still follow the standard visa and residency application procedures if they wish to live in Japan long-term.

Language barrier

A buyer must be in Japan and speak Japanese, or work closely with someone who does.

“Just buying a house doesn’t grant you anything,” says Wormann.

“To do what I’ve been doing, you need to be in Japan. And if you can’t speak Japanese or don’t have a Japanese-speaking partner, it doesn’t really make sense.”

Japan has so many intricate cultural rules that it can be hard to know “where you can bargain and where you can cut corners”, he explains.

“As long as you try, and as long as you have a broker or someone guiding you, it’s totally fine.”

Renovations are a challenge

“Old houses in Japan often have negative value. You’re essentially buying the land,” Wormann says.

Trash disposal costs in Japan are also astronomical. He does a garbage-collection round once a month, and renting a car and dumping debris cost US$300 to US$400 each time.

Be flexible and keep an open mind

Renovating a home in Japan requires a flexible mindset, Wormann believes.

“You can’t say, ‘This works in New York, so it should work in Japan.’ You need to be very curious and open, and you can’t be afraid to fail. That’s probably my biggest takeaway.”

Global Design is a series that explores design ideas and experiences beyond Singapore.