Snake year in hiss-story: Will 2025 ‘snake’ Singapore or inject new life?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

A floral display inspired by The Legend Of The White Snake at Gardens by the Bay.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Over the course of human history, snakes have acquired something of a bad rap.

The most notorious of them all is perhaps the Biblical serpent in the Garden of Eden, cunning and devious, who tempted Eve into taking a bite of forbidden fruit.

Then there is Bai Suzhen, the eponymous serpent in The Legend Of The White Snake, one of China’s four great folktales. In a Tang Dynasty version dating from the early ninth century, she is portrayed as a malevolent demon who takes the form of a beautiful woman and seduces the scholar Li Huang.

When he returns home after three days with her, he falls ill and dies. His family searches for the woman, but finds only a giant white snake.

For centuries, these snake stories have been wielded as cautionary tales, often with anti-feminist overtones. In the Renaissance, for instance, Eden’s serpent was frequently depicted with the head and body of a woman, despite the male pronouns assigned to it in some translations of scripture.

Looking back on the trail of destruction left by previous Years of the Snake, perhaps humanity would do well to heed the portent of this seemingly inauspicious animal. The havoc it wreaks usually cuts across gender, race, class and country.

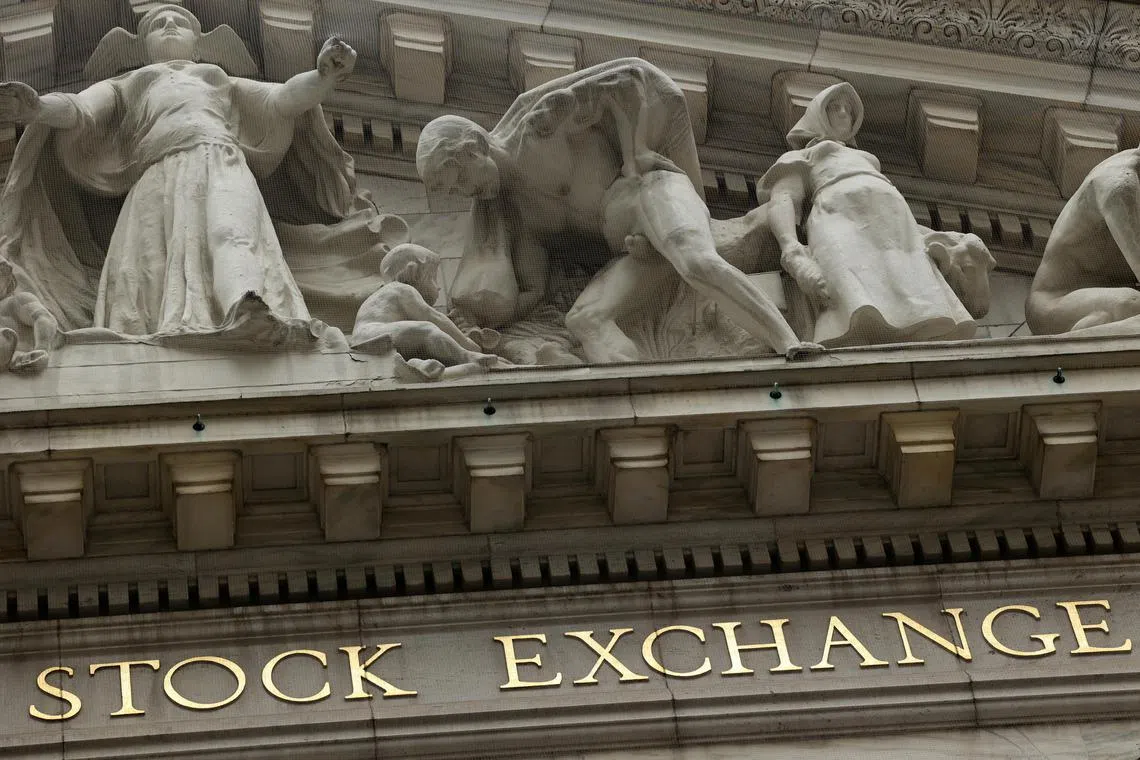

Nearly a century ago, in 1929, the world found itself in the coils of a particularly grim Snake Year. The glitz and good fortune of the Roaring Twenties screeched to an abrupt halt when Wall Street crashed in late October, triggering the start of the Great Depression.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 marked the end of the Roaring Twenties and the start of the Great Depression.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Other Snake Years have proven just as venomous. In 1977, two Boeing 747 passenger jets collided on the runway at Tenerife’s Los Rodeos Airport, resulting in 583 deaths. To this day, it remains the deadliest crash in aviation history.

In 1989, up to a million people flooded Tiananmen Square in Beijing to demand economic and political reform. The protests lasted 1½ months, coming to a swift and bloody end on June 4, when tanks and troops forcibly cleared the square.

Then in 2001 came the attacks that shook America to its core. On Sept 11 at 8.46am, the first of four hijacked planes struck the North Tower of the World Trade Centre in New York. By the end of the day, 10 buildings lay in ruins and nearly 3,000 people were dead.

And yet, just as a snake sheds its skin, humanity has been able to move past its sorrow, picking itself up time and time again as it clings to the promise to new life.

The symbolism of this reptile, too, has gone through many rounds of metamorphosis. Portrayals of the white snake took on a more sympathetic slant in the Qing Dynasty, with 18th-century works turning Bai Suzhen into an endearing character.

Once worshipped by many ancient civilisations, the snake has, at times, found itself intertwined with divinity. The Chinese goddess Nu Wa, for instance, is sometimes depicted in serpentine form, especially on tomb murals and iconography.

Some legends also claim it is the precursor to the revered dragon, though Dr Charles Wong, a lecturer of Chinese Studies at the National University of Singapore, notes that the higher the dragon rose in imperial esteem, the further the snake slunk back into the shadows.

Nonetheless, the snake is still seen as an auspicious symbol in some communities today, with parts of south-east China continuing to worship it.

“Dragons are imaginary, but snakes are real animals, so their relationship with man is much more interesting. They can bite you, but also heal you. This relationship is much more dynamic,” Dr Wong says.

Indeed, past Snake Years have tempered their bite with healing. The first effective polio vaccine was successfully tested on a small group of adults and children in 1953. That same year, the Korean War drew to a close with the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement in July.

The following cycle was an especially significant one for Singapore. The country became a sovereign nation in 1965, and will celebrate 60 years of independence under the auspices of 2025’s wood snake.

Singapore gained independence during a Snake Year in 1965 and will celebrate its 60th National Day in 2025.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

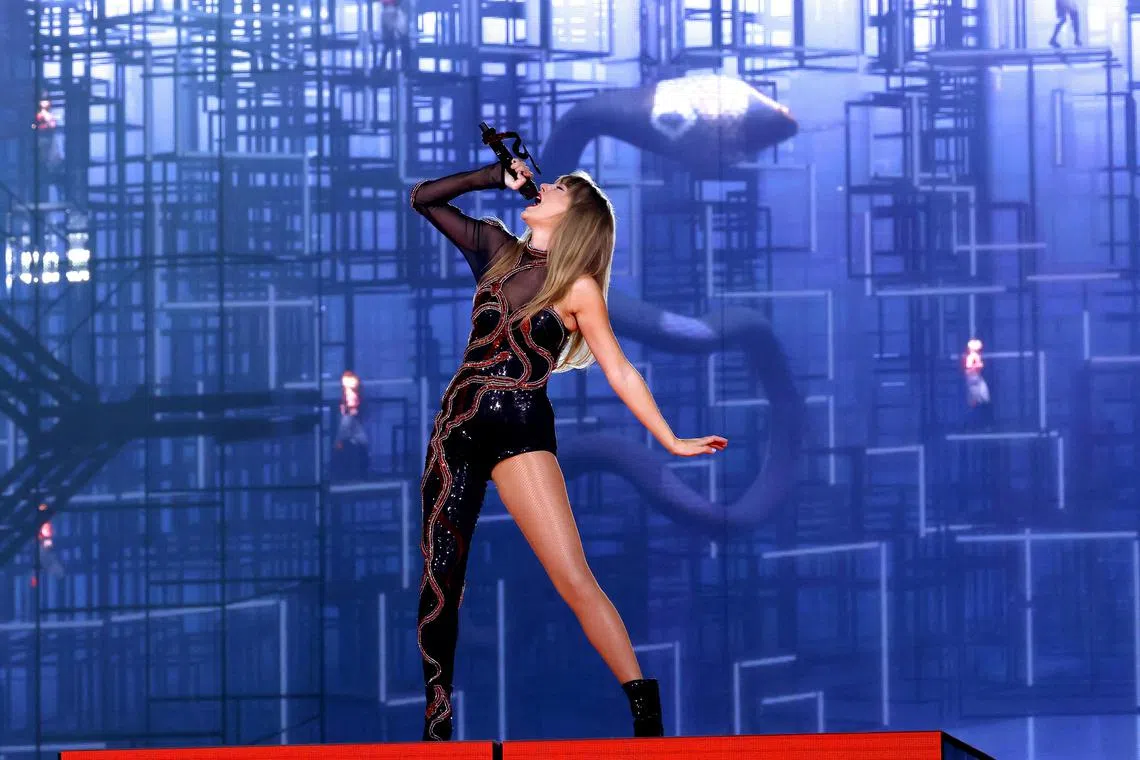

Though not as multitudinous as those born in the Year of the Dragon, snake babies count many notable figures among their ranks, such as Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881), German diarist Anne Frank (1929), Chinese President Xi Jinping (1953) and American pop superstar Taylor Swift (1989).

Swift, in particular, has a long and storied relationship with snakes. After being called one by reality star Kim Kardashian and her then-husband rapper Kanye West – coincidentally also a snake baby – she reclaimed the reptile, making it the central motif of her 2017 record Reputation.

In keeping with the snake theme, the superstar is expected to release the Taylor’s Version re-recording of that album in 2025.

American pop star Taylor Swift donned a snake bodysuit for the Reputation set of The Eras Tour.

PHOTO: AFP

Historically, Snake Years have been good for the arts, yielding massive, epoch-defining works of culture. Case in point: The first Star Wars movie premiered in 1977, The Simpsons in 1989 and Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone in 2001.

Closer to home, Singaporean novelist Amanda Lee Koe has launched her sophomore novel, aptly titled Sister Snake. This spirited retelling of the Legend Of The White Snake charts the paths of two immortal sisters across time and space.

If its plot is anything to go by, this will be a year for rebuilding broken relationships, rediscovering old pleasures and returning home – but hopefully sans the book’s chaos and bloodshed.