‘Spend first, worry later’: Why Buy Now, Pay Later is making a comeback in 2025

Sign up now: Get tips on how to grow your career and money

Once a niche offering, Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) services are now everywhere in Singapore's retail landscape.

PHOTO: UNSPLASH

SINGAPORE – Mr Amirul’s first brush with the world of Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) came in 2021, when he was in national service.

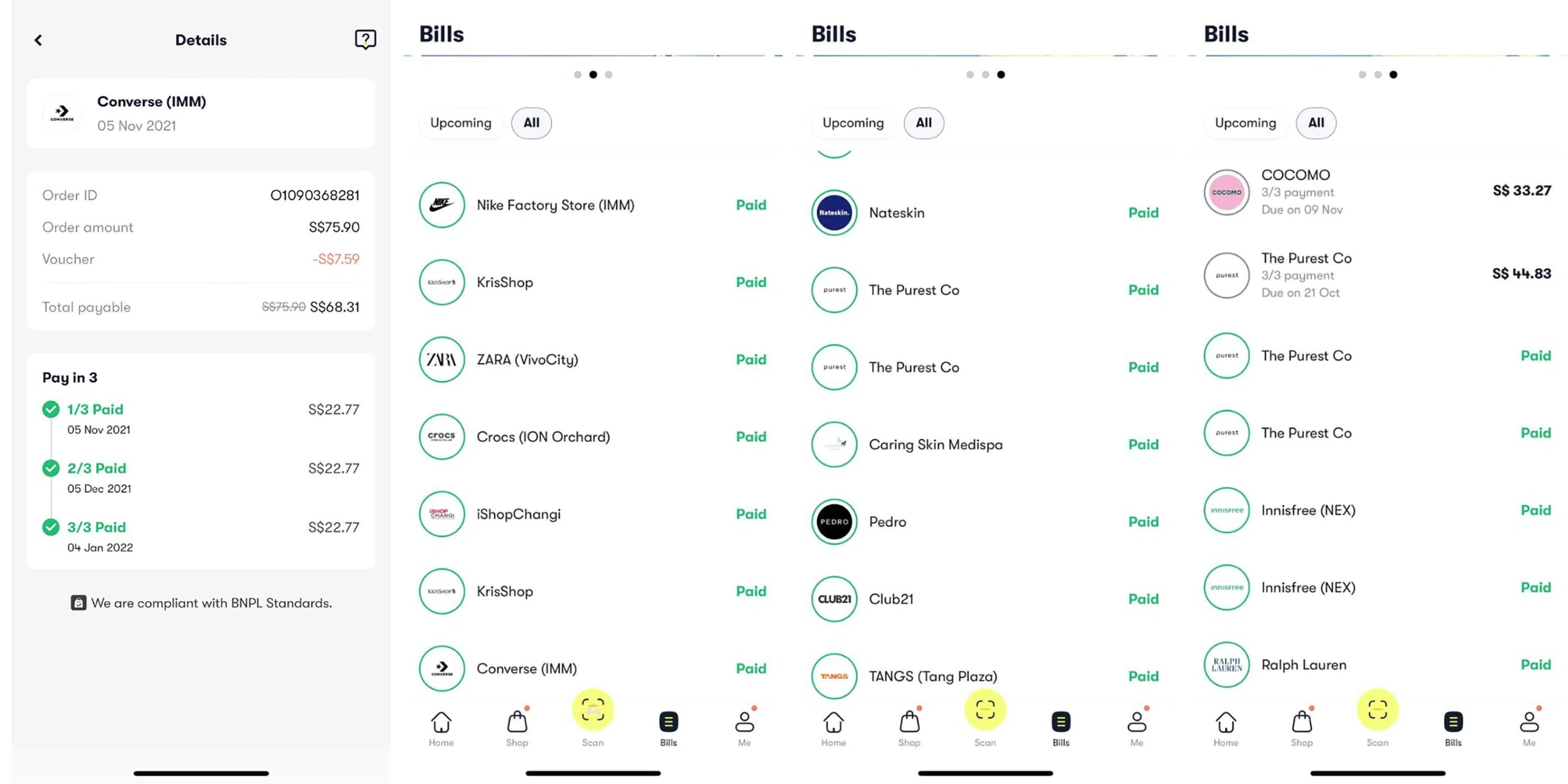

The then-20-year-old discovered that he could turn a $75.90 pair of Converse trainers into three interest-free payments of $22.77 via an app called Atome. Plus, it came with the extra incentive of a 10 per cent discount voucher.

That kicked off what Mr Amirul, now 23, describes as his fashion and skincare phase of spending $100 to $200 a month on the BNPL platform. No credit checks or lengthy sign-up process were necessary.

The tutor, who declined to give his last name, says the price of skincare products that would have cost $60 to $100 apiece upfront seemed quite reasonable after being split into smaller monthly instalments.

Therein lies the appeal of buying now and paying later.

Experts and multiple studies point to how this distinctive pricing mechanism eases the pain of buying and allows consumers to justify price tags that they might otherwise baulk at – all through a sleek and user-friendly interface.

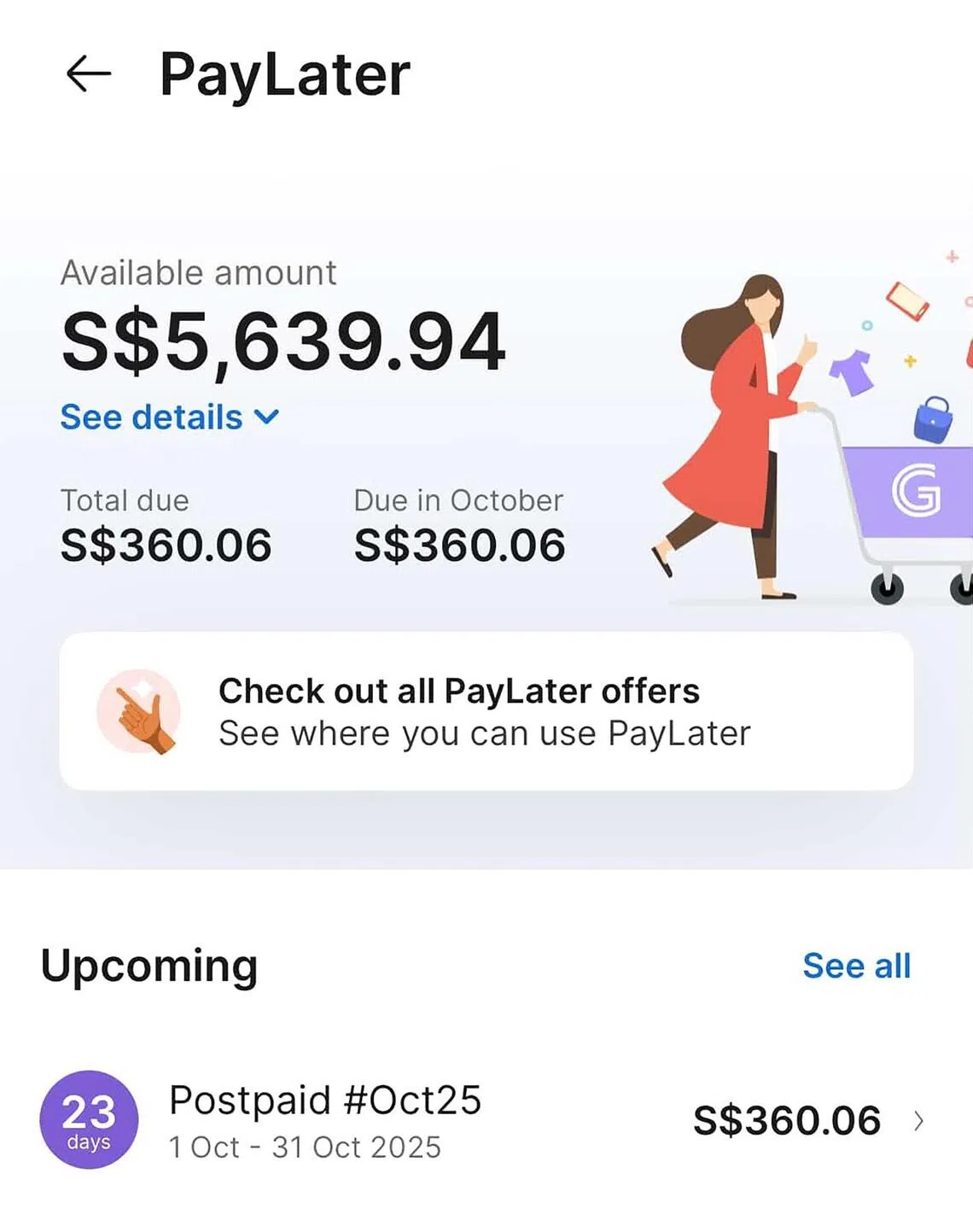

Mr Amirul has since put his Atome spending spree behind him, but now spends around $300 to $500 a month on rides and food deliveries through Grab PayLater, a BNPL provider built into the super-app’s payments system.

In September alone, he racked up $800 in expenses on Grab PayLater.

“There’s this term called luxury poverty,” Mr Amirul says ruefully, referring to the pursuit of non-essential goods and services when long-term financial milestones such as owning a home feel out of reach, particularly among the younger generation.

“PayLater is like ‘spend first, worry later’. It’s for things that you don’t need, but want.”

The Atome app interface and the transaction that started the Buy Now, Pay Later practice for tutor Amirul, who declined to give his last name.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF AMIRUL

BNPL’s comeback

His experience encapsulates a broader trend sweeping Singapore’s retail scene in an uncertain economic climate.

Once a retail novelty, BNPL has become almost-ubiquitous across the super-apps and platforms that increasingly dominate commerce in Singapore.

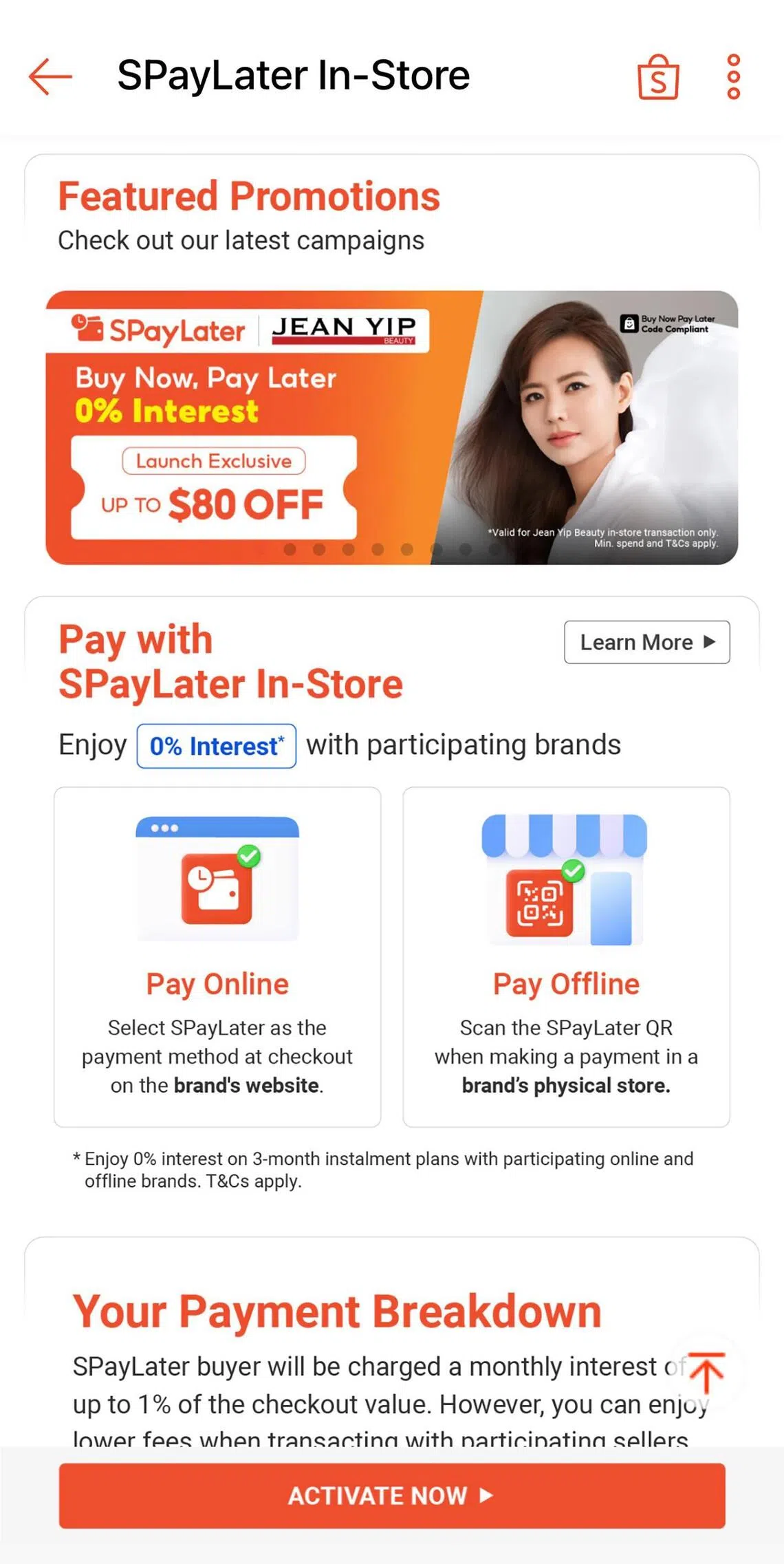

On the Grab app, users regularly receive notifications offering $10 off when making purchases through the Grab PayLater function. Meanwhile, e-commerce app Shopee blasts users with advertisements promoting its SPayLater feature, enticing users to break up the cost of their haircuts from, say, salon chain Jean Yip, into three interest-free payments.

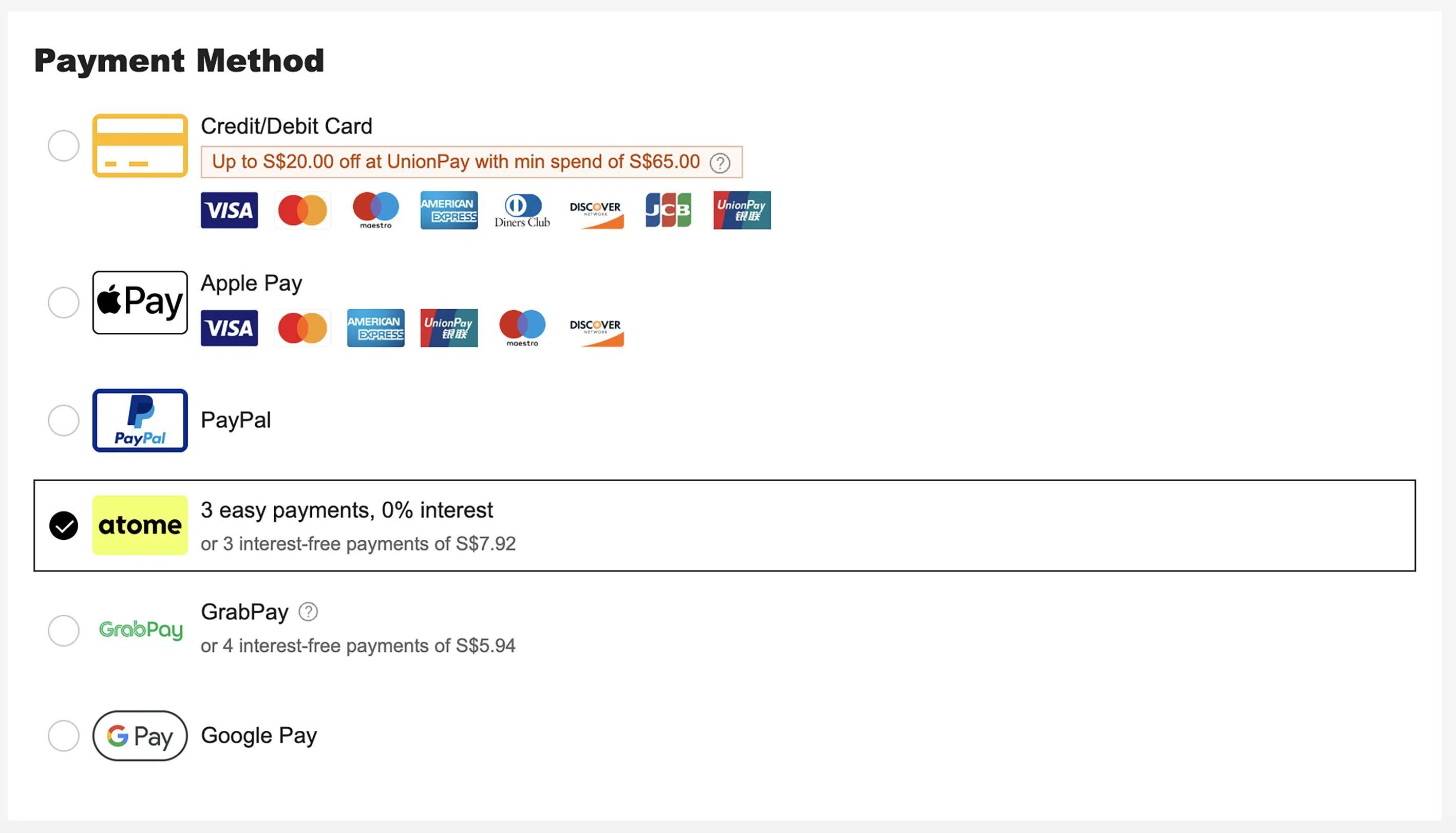

BNPL options are also now widely available – from fast fashion retailer Shein and menswear brand Benjamin Barker to ticketing platform Ticketmaster and travel booking platform Trip.com.

BNPL providers are now a visible presence across online retailers.

PHOTO: SHEIN

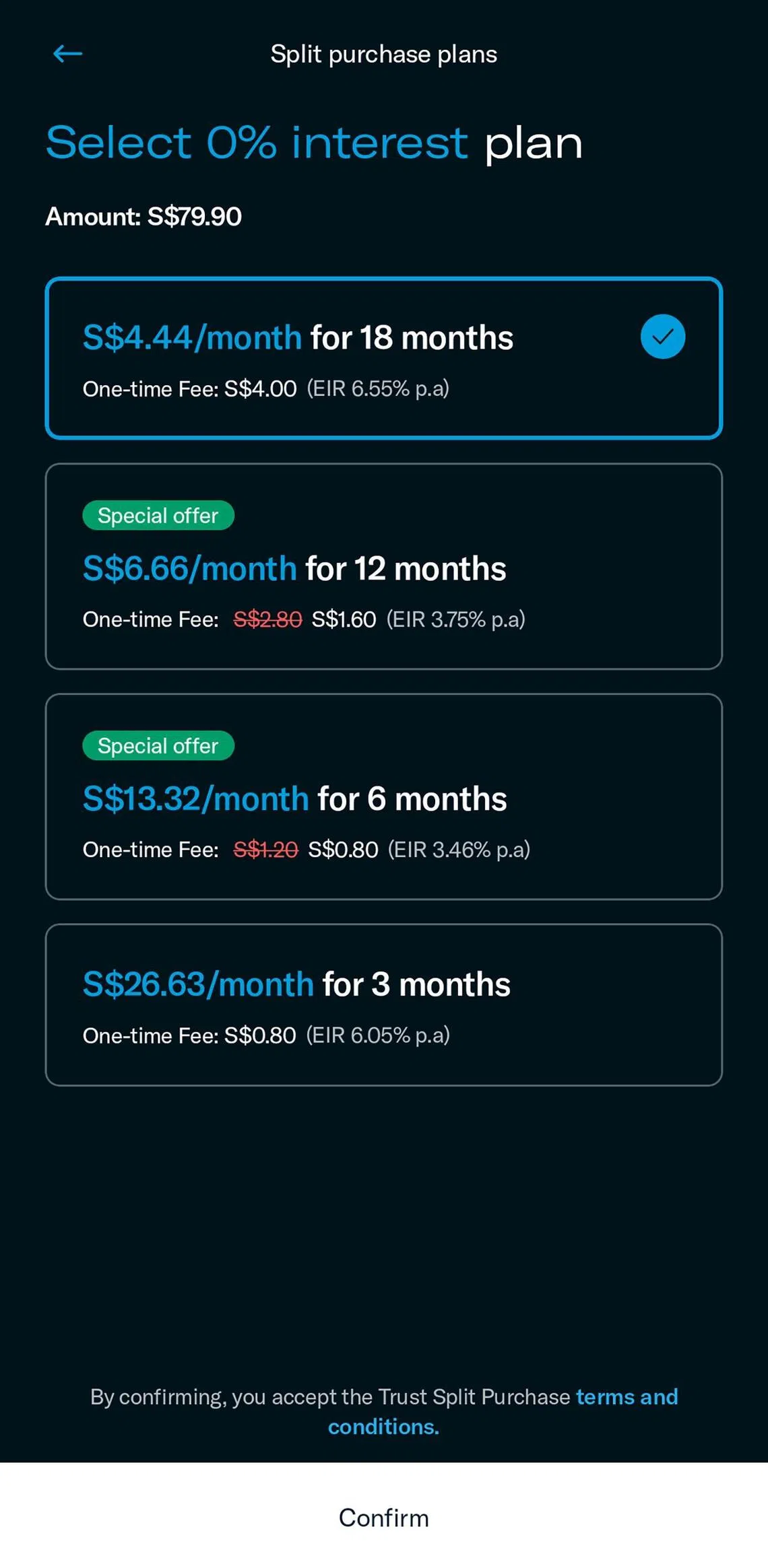

Not to be left behind, banks are responding with their own instalment plans. On digital banking app Trust, users get notifications asking if they would like to split up large credit card payments.

What is noteworthy is that this surge in BNPL adoption is not the first.

Banks, including Trust Bank, have responded with their own instalment plans.

PHOTO: TRUST BANK

When BNPL providers made their debut in Singapore during the early 2020s, it was soon followed by the retreat by forerunner entities such as Australian BNPL provider Zip in 2022, fintech start-up Pace in 2023 and rewards platform ShopBack in 2024.

Elsewhere in the world, the business model is showing its cracks. Swedish fintech firm Klarna, a BNPL pioneer, launched its initial public offering in September 2025. It was valued at US$17 billion (S$22 billion), a fall from its peak valuation of US$45.6 billion in 2021.

Klarna’s net losses in the first quarter of 2025 grew to US$99 million, more than double the US$47 million figure it reported a year ago.

As BNPL’s unique financial risks become apparent, the mid-2020s has brought with it tightening regulations from governments across the globe.

In the United States, the largest BNPL market, research by the country’s Federal Reserve found that those who report lower overall financial well-being are most likely to use BNPL. Most of these consumers say they use it as it is the only way they can afford a specific purchase.

So, what makes this wave of adoption different, and why might it go further and last longer?

According to experts, today’s growing trend of BNPL has expanded beyond big-ticket household items and retail categories it has traditionally thrived in, such as fashion, and into the realm of everyday purchases, particularly among Gen Z and younger millennials.

“This expansion into everyday essential services, not just discretionary retail, is a big (and concerning) shift,” says Dr Ben Charoenwong, associate professor of finance at the Insead business school.

“If you need a loan to buy a burger or a beauty product, was that purchase affordable in the first place? That’s the core concern with BNPL expanding into everyday transactions.”

Dr Gordon Tan, an assistant professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) who is conducting a study on public attitudes towards BNPL, adds: “Things are becoming more expensive, ever since Covid-19, and the prices haven’t really come down.”

Enter BNPL, he notes, with marketing and interfaces that present it as a friendly tool for budget management, rather than another source of debt through credit.

“It’s a perfect tool for people to realise their aspirational spending,” he says. “BNPL has inserted itself into this narrative that even though things have become more expensive, there is BNPL to help you to still spend ‘within your means’.”

Credit, but not credit

For Mr Khairihadri Kahar, 34, that is the narrative he has bought. Using Atome has been a regular part of his holiday planning since 2019.

“My parents taught me to use my own money instead of spending someone else’s,” he says, explaining his rationale for using the BNPL provider instead of a credit card when paying for flights and hotel reservations. “Spend the money you have. If you don’t have, don’t spend.”

It matters less to Mr Khairihadri that BNPL is essentially credit, albeit presented differently.

While such thinking might sound contradictory, this is simply BNPL in action.

Dr Daniel Rabetti, an assistant professor at the NUS Business School, explains that BNPL’s distinct pricing mechanism makes consumers likely to spend more. When faced with three $100 instalments versus a $300 upfront charge, the brain processes the transaction differently, even though the total remains unchanged.

This cognitive trick forms the core of BNPL’s business proposition to merchants, who pay higher fees to these purveyors than to traditional debit or credit cards, betting that customers will spend more when payments feel smaller.

For comparison, Dr Charoenwong says merchants typically pay 2 to 3 per cent of each transaction in fees to credit cards, whereas BNPL providers might charge merchants between 2 and 8 per cent.

What helps is that BNPL is treated as a type of debt distinct from traditional credit.

Unlike applying for a credit card, new users are not put through a means test to access funds of up to $2,000 in Singapore. BNPL providers need only conduct checks on users looking to increase their spending limits, and report the data to a BNPL bureau separate from Singapore’s credit bureau.

This means that BNPL spending does not factor into one’s credit score.

As such, BNPL offers merchants access to a broader group of clients, such as those who lack access to traditional credit or might otherwise find it difficult to justify the maths behind a purchase.

The framing that BNPL companies use has proven particularly persuasive among one group of Singaporeans – Gen Z.

About 79 per cent of Singapore Gen Z – those born between 1997 and 2012 – have used BNPL, the highest percentage among all age groups, according to a 2024 report by payment processing firm WorldPay.

“I use it to buy small treats and luxuries. If not, life gets too miserable,” says Mr Brandon, a 27-year-old who works in the arts sector and asked not to share his last name. He estimates paying $100 to $150 to Atome and Grab PayLater each month.

He does not have a credit card because he has a low credit rating, for reasons he declines to elaborate on.

Buy Now, Pay Later app interfaces, such as the one on Grab, are sleek and easy to use.

PHOTO: GRAB

Some of his purchases include motorcycle accessories (back when he worked as a delivery rider), meals, cab rides and a new mobile phone, the Samsung Galaxy S23. “I wouldn’t have spent it if not for BNPL,” he says.

SUTD’s Dr Tan notes that such distrust of traditional credit is prevalent. “A lot of consumers, and especially younger generations who are slowly coming into credit now as they come of age, the way they look at credit is as a predatory form of finance,” he says.

After all, the credit crunch of the late 2000s left traditional credit with negative baggage in the eyes of the general public, an attitude that many have passed down to their children.

“BNPL services allude to this idea of freedom, or BNPL as a lifestyle,” he adds. This positioning is what enables BNPL services to attract users to their service, as an easy way to pay that lives on your smartphone and is unlike traditional ideas of debt.

The super-app difference

To be sure, not everyone – young or old – is persuaded by the allure of BNPL.

A WorldPay report found that BNPL made up just 3 per cent of e-commerce purchases in Singapore in 2024. The firm projects that figure to stay the same in 2030.

For many users, discounts are the primary reason to consider this payment option.

Mr Danish Lukawski, 29, a creative agency worker, uses BNPL services only when there are discounts that make the total cost of a purchase lower compared with paying upfront.

“I’ve bought things like high-value sneakers through Atome, only because it gave a 20 per cent discount,” he says, adding that he typically pays the loan amount in full at the first available opportunity, rather than servicing it over multiple months.

Online, there are occasional posts where netizens express confusion over how liable they are for debt incurred through BNPL.

“Will they send someone up to my house to collect an amount of $84?” wrote one user in April. In response to queries, the user, who declined to share his name, stated that his debt remains unpaid.

Even as BNPL firms worldwide struggle to prove their business models are financially feasible, what is playing out in Singapore now shows hints of what the future of paying in instalments could look like.

Smaller players such as ShopBack have retreated from the space, many of them likely calculating that the cost of acquiring new customers through hefty discounts is too high to encourage widespread adoption.

However, BNPL’s growing embrace by massive platforms such as Grab and Shopee follows a different logic.

Grab notifications promoting the app's Buy Now, Pay Later offering.

PHOTO: GRAB

Grab notifications promoting the app’s Buy Now, Pay Later offering.

PHOTO: GRAB

“It’s classic loss-leader behaviour,” says Dr Charoenwong. “They’re willing to subsidise it because it drives volume and generates valuable transaction data, which they can use to cross-sell.”

Each BNPL transaction reveals valuable data – from each customer’s spending patterns to different merchants’ customer base and financial needs. This is useful when expanding one’s reach into other financial services, or creating opportunities for lending to small businesses with better screening than one’s competitors.

Launched in 2019, Grab PayLater falls under the platform’s fast-growing financial services segment. The company projects that its total loan portfolio will exceed $1 billion by the end of 2025, according to its second-quarter financial report. This amount also includes lending through its digibanks and financial services arm GrabFin.

Meanwhile, SPayLater forms one part of Shopee parent company Sea’s expansion into the fintech space. Sea rebranded its fintech offerings to Monee in May, and has a current loan book of US$5 billion.

BNPL’s resurgence in 2025 is defined by its embrace by platforms, including Shopee, and super-apps.

PHOTO: SPAYLATER

Thus far, BNPL does not pay for itself. Or at least, not yet.

“It works best as subsidised customer acquisition, not as a standalone profitable business. That’s why you see the aggressive promotions,” says Dr Charoenwong. “It’s fundamentally about ecosystem lock-in, not lending profitability.

“The model works when you’ve got cheap capital and aggressive customer acquisition goals, but the unit economics remain questionable.”

In response to queries from The Straits Times about risks to consumers, a Grab spokesperson says: “Customer protection and responsible usage are the foundations of our service. We demonstrate this commitment through strictly applying the strong safeguards outlined in the BNPL Code of Conduct.”

The company’s safeguards include avoiding aggressive solicitation (especially for in-person marketing), allowing users to deactivate Grab PayLater at any time and using repayment patterns to set spending limits.

As for Shopee, its SPayLater spokesperson says in response to queries: “When we launched, customers were understandably cautious and tended to use BNPL for larger purchases. Over time, we have seen healthy and responsible adoption, with more users incorporating the service into their daily spending in thoughtful ways.”

Both companies declined to share figures on BNPL adoption by their users or the extent to which these offerings comprise their broader fintech portfolios.

What next for BNPL?

As BNPL expands globally, regulators are often left playing a game of catch-up.

A 2024 study by Malaysia’s Consumer Credit Oversight Board study found that 69 per cent of BNPL users surveyed depend entirely on it as their sole source of financing, with more than half using it for daily essentials. Malaysia introduced new consumer credit legislation in August to require mandatory licensing for BNPL providers.

In Indonesia, BNPL-related debt reached almost US$1.9 billion in May, marking a 40 per cent increase from the previous year, according to the country’s Financial Services Authority. In August, Indonesia introduced new restrictions, requiring users to be aged 18 or above, and have a monthly income of at least three million rupiah (S$235).

Singapore’s approach is distinct because of early self-regulation. BNPL companies developed a code of conduct in 2022 with guidance from the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS).

Some of the code of conduct’s key safeguards include an 18 or above age requirement, an explicit cap on fees – late fees, for instance, are capped and cannot be compounded – and mandatory suspension of service upon non-payment.

BNPL providers also share their users’ BNPL balance and payment information with one another, which the code indicates should be used to assess whether to increase a user’s spending limit.

This approach has helped weed out weaker players and instilling consumer confidence, as the sector moves away from its initial “Wild West” phase of the early 2020s, says Dr Rabetti.

“By international standards, Singapore’s BNPL safeguards are robust and more stringent than most,” he notes, adding that he believes current regulations are adequate, considering that BNPL makes up only a small fraction of transactions.

However, some experts disagree.

Dr Tan says: “It’s an easy form of credit, but it’s not regulated as such.” He argues that BNPL debt should be reported to the credit bureau as part of each consumer’s credit utilisation.

He adds that the policies used by BNPL companies to assess whether to raise or lower spending limits remains a black box, which marks a contrast from more stringent transparency requirements faced by banks and other financial institutions.

A source of moral ambiguity in the BNPL model is that providers have incentives to use their data to find the sweet spot of upping consumers’ spending, without the expense of loan defaults.

The industry’s current code of conduct is voluntary and industry-led, but not statutory. “MAS does not collect data on how many users are hitting their BNPL limits, which limits regulatory visibility,” says Dr Charoenwong.

Like others, he believes that mandatory credit bureau reporting should be instituted, as well as stricter limits on what categories of spending can be financed through BNPL.

That BNPL is increasingly expanding into essential services such as transportation and food creates new vulnerabilities, as people in debt may prioritise BNPL repayment to maintain access to these services, over other forms of debt. This presents new ethical considerations, he says.

“The fundamental question is whether we’re facilitating financial inclusion or just enabling consumption beyond people’s means,” he adds. “When BNPL is used for discretionary purchases or daily essentials, that signals financial fragility, not sophistication.”

As much of BNPL’s growth has been driven by venture capital funding and platform subsidies, in pursuit of greater scale and market share, the question that remains is just how sustainable BNPL is.

“As capital tightens, we’ll see whether the unit economics actually work or if this is just another chapter of fintech burning capital for growth,” says Dr Charoenwong.

One can only hope that Singapore’s more conservative regulatory approach will protect the market “from the excesses we’ve seen elsewhere”, he adds.