Some cancer cells said to escape destruction by immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

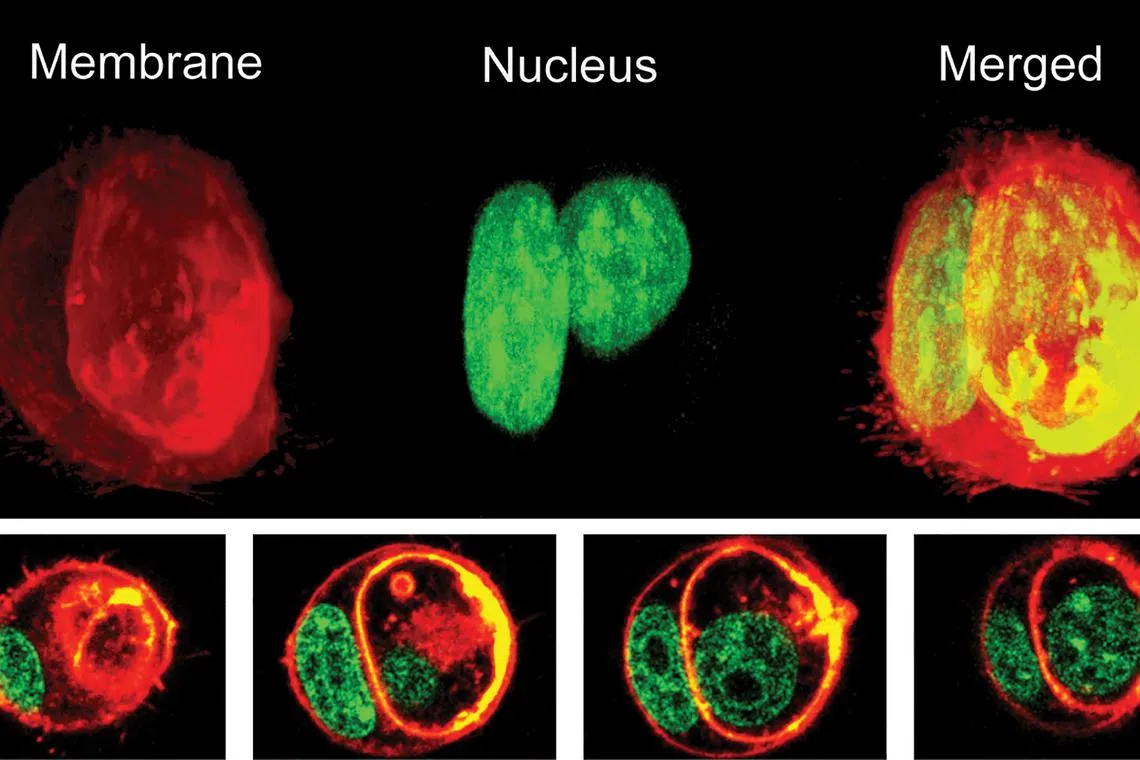

A 3D projection of tumour cells organised in cell-in-cell formation, with the cells’ nuclei and membrane being attacked by a T-cell, in blue.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Follow topic:

UNITED STATES – In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells.

The finding, they suggested in an article published recently in the journal eLife, may explain why some cancers can be resistant to treatments that should have destroyed them.

The research began when Dr Yaron Carmi, an assistant professor at Tel Aviv University, was studying which T cells of the immune system might be the most potent in killing cancers. He started with laboratory experiments that examined treatment-resistant melanoma and breast cancers in mice, studying why an attack by T cells engineered to destroy those tumours did not obliterate them.

He was looking at checkpoint inhibitors, a particular type of cancer therapy. They involve removing proteins that ordinarily block T cells from attacking tumours and are used to treat various cancers, including melanoma, colon cancer and lung cancer. But sometimes, after a tumour seems to have been vanquished by T cells, it bounces back.

Dr Carmi, who loves looking at cells under microscopes, started peering at the tumours while the T cells were attacking them.

“I wanted to see the killing, the actual killing,” he said.

Every time, though, he saw some giant cells that remained after the T cells had done their job.

“I wasn’t sure what it was, so I thought I would take a closer look,” he said.

The giant cells turned out to be cancer cells that were harbouring other cancer cells, protecting them from destruction. Once the cancer cells escaped to their hiding places, T cells could not get to them, even if the immune system killed the cancer cells serving as cellular bunkers.

Cancer cells, he said, can remain in hiding for weeks or months.

When he removed the T cells from the petri dishes, the cancer cells came out of their shelters.

He looked at human cells from breast cancers, colon cancers and melanomas and saw the same phenomenon. But blood cancers and glioblastomas, the deadly brain cancers, did not form the cell-in-cell structures.

Perhaps, Dr Carmi reasoned, it might be possible to prevent cancer cells from taking refuge. He decided to examine the genes involved in this defence mechanism. Blocking those genes, he discovered, also blocked the ability of T cells to attack the tumours.

“I realised this is the limit of what the immune system can do,” he said. “Our immune systems cannot win.”

Images provided by Dr Yaron Carmi and Amit Gutwillig show a series of 3D projections and optical slices across the height of tumour cells organised in cell-in-cell formation.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Others, while fascinated by the discovery, say many questions remain.

“It’s definitely an interesting paper with some strong, compelling observations,” said Dr Michel Sadelain, an immunologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where he heads the centre’s gene transfer and gene expression laboratory. But, he asked, how relevant is the finding in disabling immunotherapies in the real world?

Dr Marcela Maus, director of the cellular immunotherapy programme at the Mass General Cancer Center, said the discovery showed what might be a new cancer cell defence mechanism.

“We have seen that tumours can hide from the immune system, including a kind of ‘impersonating’ immune cells, but I don’t think we’ve seen tumour cells hide inside each other,” she said. “I do think it needs to be replicated to gain full traction.”

Dr Jedd Wolchok, director of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, had the same reaction.

“I’ve heard about cancer cells feeding off themselves, feeding off their neighbours, putting out exosomes,” he said, referring to little pouches of signalling chemicals. “I guess this is the next step: hiding inside your neighbour.”

One possible remedy, he said, might be to foil the cancer cells by treating a patient with immunotherapy for a short time, stopping, then treating him or her again. That could be in keeping with new questions about how long patients should be treated with these expensive and toxic drugs. The current advice is to treat for two years.

But, Dr Wolchok said, “Many of us are asking, ‘Can you get away with less?’”

He cautioned, though, that the immunotherapy the Tel Aviv group used was not a standard one in cancer patients.

For now, he said, while the discovery is “a really innovative observation”, it remains to be seen whether it will lead to improvements in the treatment of cancer patients. NYTIMES