Rise of stepfamilies in the US and its impact on eldercare

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

As studies show that ties in stepfamilies are usually weaker than those in biological ones, experts are concerned that a "step gap" can affect eldercare.

PHOTO: PIXABAY

UNITED STATES – The encounter happened years ago, but professor emerita Beverly Brandt remembers it vividly.

She was leaving her office at Arizona State University, where she taught design history, to run an errand for her ailing stepfather. He had moved into a retirement community nearby after his wife, Prof Brandt’s mother, died of cancer.

As his caregiver, Prof Brandt spoke with him daily and visited twice a week. She coordinated medical appointments, prescriptions, requests for facility staff – the endless responsibilities of maintaining a man in his 90s.

Maybe she looked especially frazzled that day, she said, because a long-time colleague drew her aside with a startling question.

“Beverly, why are you doing this?” he said. “He’s not a blood relative. He’s just a stepfather. You don’t have any obligations.”

“I was dumbfounded,” Prof Brandt, 72, recalled. “I still can’t understand it.”

She was five when her father died. Three years later, she said, her mother married Mr Mark Littler, an accounting executive and a “wonderful” parent.

Retired professor Beverly Brandt with a photograph of her stepfather, Mr Mark Littler, whom she took care of for over 12 years until he died at 98.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

“He’d come home from a gruelling job, change out of his good clothes, then carry me around the living room on his back,” she recalled. Later, he introduced her to the symphony and the theatre, funded her graduate education and mentored her as she entered the academic world.

Even as he descended into dementia, he continued to recognise her and know her name. Why would she abandon him?

But the views her colleague expressed were most likely not unusual. Studies repeatedly show that, unlike the enduring relationship between Prof Brandt and Mr Littler, ties in stepfamilies are usually weaker than those in biological ones.

Because the number of American stepfamilies has steadily risen, sociologists and researchers now worry about a “step gap” that could affect eldercare. Given the country’s dependence on family caregivers, the gap could strand many seniors who need help.

“We have more reconfigured families than ever before, and these families may increasingly rely on someone who’s not a biological child,” said Professor Deborah Carr, a Boston University sociologist.

“In general, those relationships tend to be less close. Children are less likely to provide assistance to a step-parent.”

Calculating the growth in stepfamilies is not simple, but a demographic analysis published in 2023 estimated that about 16 per cent of Americans over age 70 have at least one stepchild. Among couples in which one partner is over 50, more than 40 per cent do.

This partly reflects the high divorce rate of the 1960s and 1970s, Prof Carr said, but also the more recent growth of “grey divorce”, followed by remarriage or repartnering.

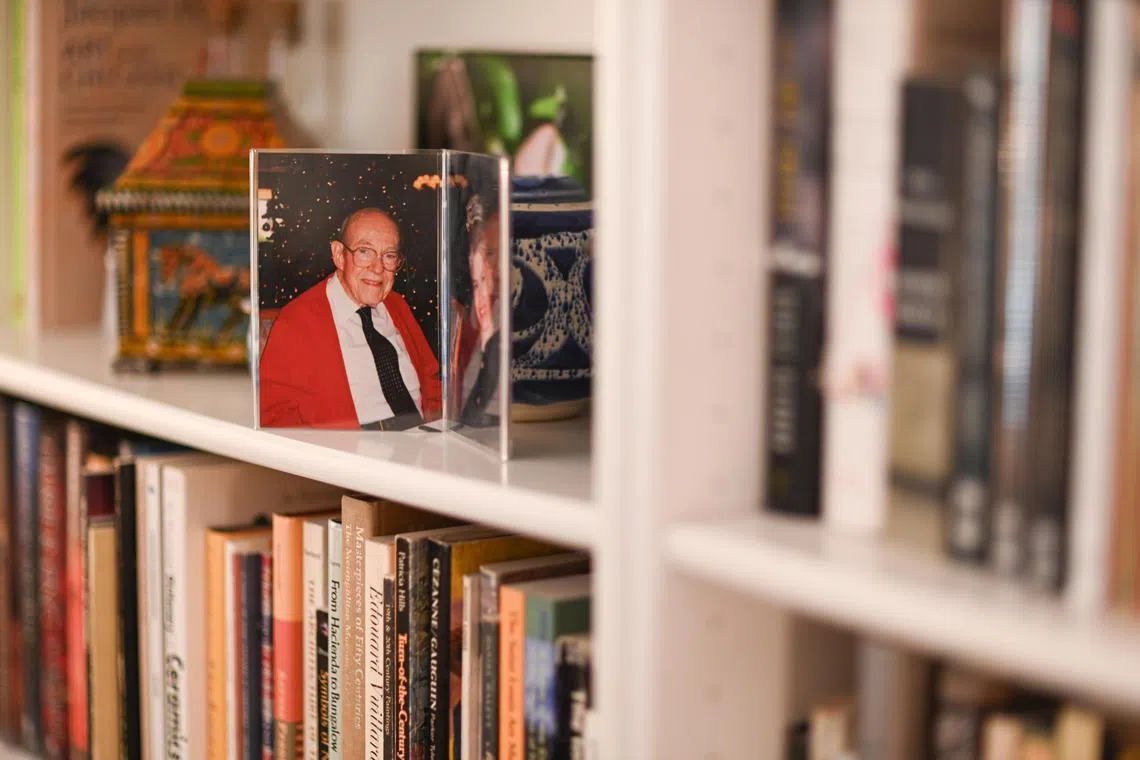

A photograph of Mark Littler at the home of his stepdaughter, Beverly Brandt.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

The proportion of older adults in second or later marriages climbed from 19 per cent in 1980 to 30 per cent in 2015. The number of older adults cohabitating, whose family ties also generally prove less close, has soared as well.

“When divorces occur later in life and children are adults, it really changes the equation,” said Professor Merril Silverstein, a sociologist at Syracuse University who has investigated intergenerational relationships.

The age at which a step-parent entered a child’s life, and whether they lived together and for how long, influences the quality of the relationship, studies show.

“When a new father comes in and you’re in your 50s, are you going to call him dad?” Prof Silverstein asked.

Prof Brandt’s older brother and sister spent less time in a home shared with their stepfather, she said, and neither developed as strong a relationship with him as she did.

The circumstances that lead to stepfamily formation also play a role. Did a parent remarry after being widowed? Or was the marital dissolution due, instead, to divorce?

As parents age, “there’s a lot of negotiation and uncertainties”, Prof Silverstein said. “Who has the right to make decisions for step-parents becomes murky.” Such families can experience what is called “role ambiguity”, he said, creating doubts about “what the social expectations are”.

Overall, stepchildren provide less care to older adults. A 2021 study led by Dr Sarah Patterson, a sociologist and demographer at the University of Michigan, found “a substantial ‘step gap’” in national data.

Among older adults in need of assistance, almost half of those with only biological children received care from them. Among those in stepfamilies, fewer than a quarter did.

“Even older adults themselves are less likely to expect stepchildren to help them later in life,” Dr Patterson said. Her team found that in stepfamilies, seniors were more likely to get help from partners than those in biological families.

Because stepfamilies are larger, the pool of potential caregivers expands. But a 2019 study found that the decreased likelihood of adult children spending time supporting a step-parent, compared with a biological one, outweighed the increased size of the family network.

Policymakers could encourage eldercare within stepfamilies by including them in family-leave laws. Although the federal Family Medical Leave Act explicitly includes stepchildren in its definition of sons or daughters, family definitions vary significantly in the 13 states (and the District of Columbia) that have enacted family-leave laws, and in employer-provided programmes.

“Some policies may not clearly include stepchildren, making it challenging for them to access the same benefits as biological children,” Ms Nicole Jorwic, chief of advocacy for the organisation Caring Across Generations, said in an e-mail.

Prof Brandt, wondering to herself what planet her colleague hailed from to warrant such an inquiry, left campus to handle whatever problem her stepfather was experiencing that day. Over 12 years, she supervised his move from the facility’s assisted living section to its nursing home to memory care. She was with him when he died at 98.

“I’d do it all over again,” she said. “In a heartbeat.” NYTIMES