One of a kind: How three Singapore professionals carved out niche careers

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Water sommelier Sam Wu, bow-maker Paul Goh and intimacy coordinator Rayann Condy are three people in Singapore pursuing their interests via highly niche jobs.

PHOTOS: GAVIN FOO, AZMI ATHNI, AWARE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Doctor, lawyer, content creator, football player – these are some of the jobs to which kids these days might aspire. But how about violin bow-maker or water sommelier?

Arguably, in modern capitalist society, the most important thing about your day job is the pay cheque you get out of it.

In Singapore, that sense is heightened by parental and environmental pressures to pursue “prestigious” careers in fields like medicine or law.

But even as technology might make today’s jobs obsolete by tomorrow, society’s preconceived notions of what makes a viable career are evolving.

More people are trying to find meaning in the work they do and not just a high salary.

According to a 2024 survey by the Jobs That Make Sense platform and Manpower recruitment agency, 98 per cent of 2,000 adults surveyed in South-east Asia said having meaning at work was important to them.

Many have taken “meaning” to be pursuing their passion and interests – sometimes venturing where few others have gone and forging a new professional trajectory for themselves.

The Straits Times talks to three people who have charted unconventional career paths – and in doing so, have become one of just a few people, if not the only person, doing that job in Singapore.

The intimacy coordinator: Rayann Condy

Ms Rayann Condy (far left) intimacy coordinating and directing on a film set in Taiwan in April.

PHOTO: CHRIS STOWERS

Romance is a beloved genre in film and television, but on-screen portrayals of intimacy often make for awkward viewing.

This is partly because of the sense of taboo that comes with watching something that is usually a private affair.

And one cannot help but think: Even if the actors in these shows and movies are professional pretenders, surely it has to be strange and uncomfortable to get so up close and personal with your co-worker, right?

In recent years, due to the #MeToo movement that gained prominence in 2017, it has become increasingly clear that the answer is frequently “yes, very much so”.

The concept of intimacy coordinators or intimacy directors – members of the crew who help the production navigate these tricky scenes – has gained prominence in Hollywood in the years since.

Now, thanks to Canada-born, Australia-raised theatre veteran Rayann Condy, Singapore productions can embed intimacy coordinators within their own crews.

In 2024, she worked as an intimacy coordinator/director on local productions such as Pangdemonium’s staging of the play Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? and Mediacorp’s period boxing drama The Last Bout.

Ms Condy, who is in her 40s, is one of a very small group of professionals who take on intimacy coordination work in Singapore.

She may be the only person here with a formal, Sag-Aftra-accredited certification from Intimacy Directors and Coordinators, the largest organisation that trains and certifies intimacy professionals worldwide. Sag-Aftra is an American labour union representing a range of media professionals including actors, stunt performers and voiceover artists.

“I began studying for my certification at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. I did the first two levels – which are open to anyone – remotely over Zoom. The third and final level is by application only, and I had to fly over to New York a few times early in 2023 to do in-person sessions for those,” says Ms Condy, who arrived in Singapore in 2004 and is now a permanent resident.

A common misconception about intimacy coordinators is that they are sex coaches or couples’ therapists. But they are more akin to choreographers and welfare officers, and ensure that actors’ personal boundaries are respected without compromising the director’s storytelling goals.

Ms Condy says her income depends on the project. “In other parts of the world like the US, UK and Australia, rates are laid out by the performing arts unions and have been benchmarked to what fight choreographers are paid.”

Ms Rayann Condy (second from left) intimacy coordinating and directing on a film set in Taiwan in April.

PHOTO: CHRIS STOWERS

Much of her training revolved around advocacy, negotiation practices, conflict resolution and understanding power structures within the context of a film set or theatre stage.

On a recent job, she found her training coming in useful during a costume fitting.

“The director – a very well-meaning person – told one of the actors: ‘I feel like this character’s shirt should be a bit more open. Could we shave your chest hair?’ And I immediately saw the actor’s face flicker and shoulders tense up,” she notes.

As intimacy coordinator, Ms Condy saw that as her cue to interject before the actor felt obliged to compromise.

“I had to say, ‘That looked like a no to me.’ And the director immediately accepted that, offered another solution that was acceptable and everyone moved on. The actor felt respected and the director still got what they needed from the scene.”

Had Ms Condy not intervened, the actor might have given in and ended up feeling uncomfortable or violated – over a matter that the director may not even have felt that strongly about.

“What I try to do is bring it back to the storytelling. What are we trying to communicate here and what are some ways we can do this? Let’s take a step back and try to problem-solve, rather than question why someone doesn’t want to do something. That’s one boundary, and one question, which I don’t entertain,” she says.

It is both a help and hindrance that she is an experienced actor and director herself, she notes.

“One thing I had to learn early on was just switching off the directorial instincts when I’m in intimacy coordinator mode, because if not, you run the risk of stepping on toes.”

While she has been in the performing arts for more than two decades, there was a blip in her early 20s when she pivoted to something more practical – law – but switched back soon after.

“I did about three-quarters of my degree and then realised, you know what? I don’t actually want to be a lawyer. I still want to be in the arts, I want to carry on in the performing arts,” she says.

At that time in the early 2000s, some of the veteran teachers at Australia’s leading performing arts schools – the National Institute of Dramatic Art and the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts – set up an acting programme at Lasalle College of the Arts.

Ms Rayann Condy on set for a directorial project for Aware.

PHOTO: AWARE

“I came to Singapore and never quite left,” says Ms Condy, whose husband is Singaporean actor Brendon Fernandez.

In 2025, she hopes to make some headway in setting up Singapore’s own formal training and certification for intimacy coordination work. “The foundational courses are more affordable and can be done online – but it’s that final overseas leg which is a big hurdle.”

Meanwhile, she feels that she has found her “dream role”.

“As someone who has acted, directed and produced across theatre, television and film, this is a space where all my skills, experience and understanding of each role comes together,” she says.

“I only wish this job had existed when I was younger. At the same time, when navigating the trickier aspects of the work, it helps to have a bit more life experience – so maybe it came at a perfect time for me,” she adds.

The violin bow-maker: Paul Goh

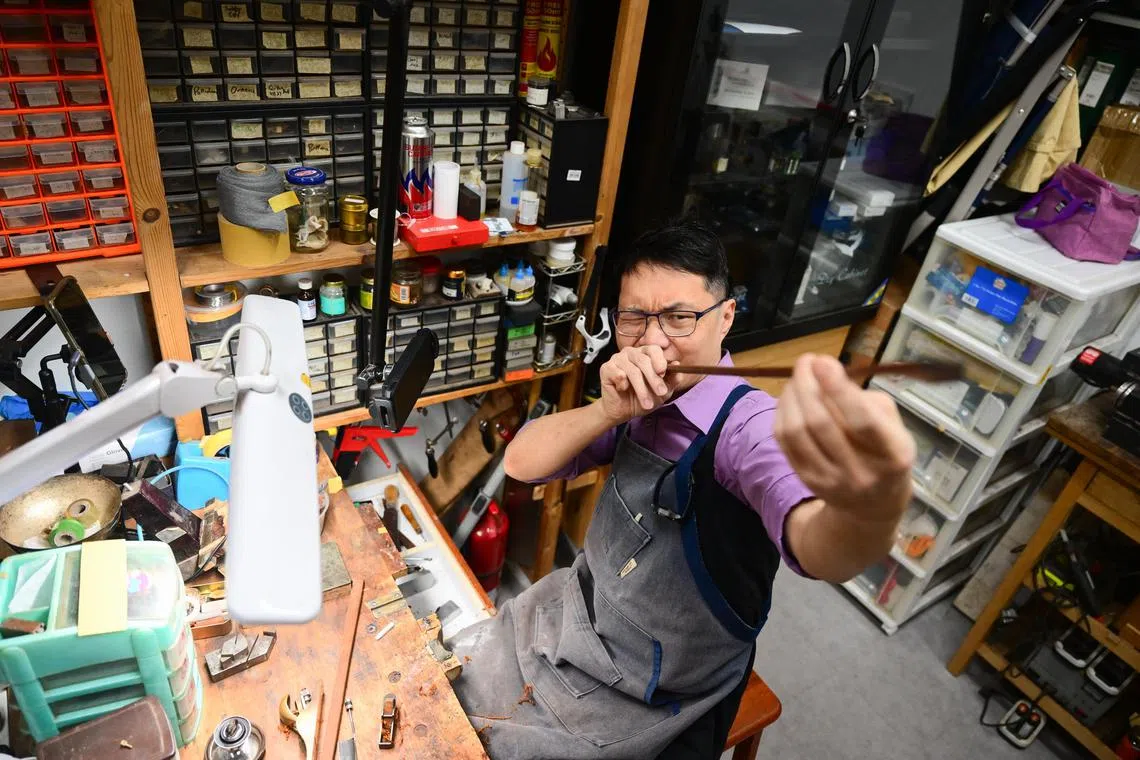

Mr Paul Goh learnt how to shape and smooth the wood for the purpose of creating a French bow

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

When Mr Paul Goh, 49, was a student in The Chinese High School – now part of Hwa Chong Institution – in the late 1980s to early 1990s, he played the viola in the school’s orchestra.

This meant he spent much of his time after school in the dingy orchestra room, located in one of the obscure crannies of the campus’ tower block. Clutter had accumulated there over the years, including a stack of condemned books.

One particular book caught his eye.

“It was a Chinese translation of a book about violin-making. I was fascinated by it, especially the part about bow-making, and the difference that the type and quality of the bow makes to the sound of the violin. It inspired me to experiment on my own bows.”

But the experiments remained a hobby. Mr Goh pursued a practical career in education; first obtaining a degree from the National Institute of Education (NIE) before returning to teach at his alma mater and then rotating into an executive role at the Ministry of Education (MOE).

Yet, as he headed into his 30s, he found himself wondering if there was something else out there for him.

“Some of the initial idealism of my youth had given way to a more realistic understanding of how things actually work,” he says.

As he pondered a career switch, he recalled the moment in the orchestra room with the violin-making book.

“I had continued as an amateur viola player even after leaving school, so I still had an interest in music. It got me thinking: I like music and I like to work with my hands, so why don’t I combine both?” he says during an interview at his workshop in Waterloo Centre.

Archetier Paul Goh at his workshop in Waterloo Centre.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

Mr Goh had a heart-to-heart chat with his wife Anna, now 47 and also in teaching. The couple had met while pursuing their undergraduate degrees at NIE.

“We figured that if I could make it as a bow-maker, it would allow me the flexibility to spend more time at home and with church work,” he says.

At the time, in 2006, the couple had two children aged three and one respectively. A third child came along some four years later.

With his wife’s support, Mr Goh flew to the United States once his MOE bond came to an end that year, and enrolled in the bow-making department of the Violin Making School of America in Utah. His family joined him a few months later.

There, he learnt the intricate craft of making modern bows for Western stringed instruments, as developed by Frenchman Francois Xavier Tourte at the turn of the 19th century.

His instructor was Mr Paul Prier, who was one of the sons of the school’s founder, the late acclaimed luthier Peter Paul Prier.

Learning under the younger Mr Prier was a largely self-directed affair, which suited Mr Goh well.

“I was very motivated to make the most of my time there, but I also found that I could sit at my workbench for hours and hours, just working at honing the craft.”

Mr Goh learnt how to shape and smooth out the wood for the purpose of creating a French bow; and how to create and assemble the other parts, such as the horse-tail hair that makes contact with the instrument, and the frog that holds the hair in place.

Archetier Paul Goh using heat to shape a bow at his workshop in Waterloo Centre.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

He also learnt how to listen to the wood that would comprise the main part of the bow, by listening to the sound of the strokes while planing the wood.

If made correctly, a bow can last many years. There are bows that are over 200 years old.

During his studies, he earned extra income by helping out at Mr Prier’s carbon-fibre bow-making business. Upon graduating, the company sent him to China for about a year, where he helped with quality control and used his command of Mandarin to work directly with suppliers.

The opportunity was crucial in helping him forge much-needed connections to start his own bow-making and repair business.

Meanwhile, in Singapore, his friends and acquaintances from the professional and amateur classical music scenes were impatiently waiting for the island’s first and only archetier to begin taking orders.

“Everyone was quite excited to finally have a bow-maker here – someone with the knowledge and craftsmanship to help with servicing and repair,” he says.

Previously, professional players would have to go overseas to purchase or fix their bows. “People didn’t really have the habit yet of servicing their bows,” adds Mr Goh.

Since his return to Singapore in 2009 to start his bow-making career in earnest, Mr Goh has not looked back. Anyone who wants to order a bow from him will have to wait at least a year for him to work through his waitlist.

They can expect to pay upwards of $5,000 each for a handmade bow made with materials such as pernambuco (a type of Brazilian hardwood), ebony wood, gold, silver, mammoth ivory, abalone shell and horse-tail hair.

“It takes anywhere from 50 to 80 hours for me to finish one bow, depending on the complexity. And that is followed by a whole process of fine-tuning the bow to the specific needs and comfort level of the client,” he says.

There have been low points – a period in 2011 to 2012 when he entered several international bow-making competitions but did not win the accolades he had hoped for.

“It was quite a depressing period. I failed to win anything at three different competitions, even though I thought my work was quite good,” he says.

He worked hard to hone his skills, and even flew out to Lille, France, in 2011 for a two-week stint with Mr Yannick Le Canu, a well-regarded and award-winning master archetier with a four-year waitlist for his bows.

The effort paid off: He won two certificates of merit at the Violin Society of America competition in 2016.

Another mentor also gave him some valuable advice, says Mr Goh.

“He said to me, ‘You’re doing well. You have a business and clients. Why are you worrying about competitions?’

“That’s when I realised: Yeah, why am I worrying about competitions? So I was able to put that behind me and focus on continuing to make my best work and, more importantly, serve my clients.”

Despite charting an entirely new and uncertain path for himself, Mr Goh says he has no regrets in his pursuit of this unusual career.

“Every bow is a new challenge and I still find it so satisfying to create something with my bare hands – especially when it is used to make beautiful music.”

The water sommelier: Sam Wu

Mr Sam Wu is one of very few certified water sommeliers in Singapore.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

There is not much to say about water as a beverage, other than that it is something people drink to survive, rather than enjoy.

These days, people are even turning to colourful water bottles and artificial flavour enhancers to make it more fun to drink.

But Mr Sam Wu, certified water sommelier, has a different outlook.

“People sometimes think water is just water. And maybe that is true about tap water, but natural mineral water – from natural springs – can have very rich flavour profiles and may even have health benefits,” says the 33-year-old.

For instance, he says, if you have trouble sleeping, but are not keen on adding supplements to your daily vitamin regimen – magnesium-forward spring water might be of interest.

And for those concerned with their calcium intake, such as vegans or lactose-intolerant people, calcium-rich water could be an option.

“Some studies have shown that this might be one of the more efficient ways of delivering nutrients to your body, because the calcium in mineral water is highly bioavailable,” says Mr Wu. Bioavailability refers to the ability of a substance to be absorbed and used by the body.

While Mr Wu is a treasure trove of water knowledge now, it was not part of his vision when he graduated from university in London back in 2015.

He had completed his undergraduate studies in environmental engineering at University College London, followed by a master’s degree in sustainable energy at Imperial College London.

“But it did not really matter what I studied in school, because I always knew I would be joining my family’s apparel business once I graduated. As the eldest son, that was just what was expected of me,” says Mr Wu, who has a sister, 31, and a brother, 26.

But in 2017, after just a few years working at the company’s factory in Cambodia, Mr Wu found himself slipping into a mild bout of depression.

“I began to realise that the work just wasn’t for me. I didn’t enjoy it and could not drum up any passion for it. I was just forcing myself to get through it,” he says.

He found solace on social media and came across a video by a German man extolling the virtues of natural spring water. That man turned out to be water sommelier Martin Riese, a self-proclaimed water advocate.

To water sommelier Sam Wu, water is more than just a bland beverage.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

“I just thought it was so interesting that something as simple as water has so many layers to it. I wanted to learn more,” says Mr Wu.

He enrolled himself in a two-week water familiarisation course at the Doemens Academy near Munich, Germany. The academy, founded in 1895, has traditionally focused on brewery education and training, but launched a water sommelier course in 2011.

Mr Wu and 15 to 20 other students from all over the world partook in an intensive fortnight of water education. He learnt how to serve water and tasted more than 100 brands of bottled spring water to understand the finest nuances – from carbonation and off-flavours to the type of mineralisation.

For instance, he learnt that water with more calcium bicarbonate is fuller-bodied than water with more calcium sulphate, which tends to have a dry mouthfeel.

However, coming back to Singapore to make a living as a certified water sommelier was – and continues to be – a bit more challenging.

“Looking back, I think I was a bit crazy,” says Mr Wu with a laugh. “Especially when the Covid-19 pandemic hit a year later. I used that time to just spread the word via social media, to start seeding water education in Singapore. I was fortunate that my family was supportive and that they continue to support me.”

He slowly built a customer base by offering masterclasses and tasting experiences, and importing and supplying bottled water to hospitality businesses and consumers on his website ( thewatersommelier.sg

These brands include Vichy Catalan ($69.90 for 12 1-litre bottles), saline-forward, naturally carbonated water from Spain; and Hildon still water ($68.80 for 12 705ml bottles) from south-east England, which was reportedly favoured by the late Queen Elizabeth II of Britain.

There have been highlights, such as a partnership with Marina Bay Sands, to provide a selection of bottled still and sparkling waters to the hotel’s Paiza Collection suites.

More recent is a collaboration with Restaurant Fiz, which is under the ABR Holdings group that also manages the Earle Swensen’s restaurants in Singapore.

“I’ve known (ABR Holdings executive) Ang Jun Hung since university. When the group launched Restaurant Fiz in 2023, there was an intention to reinvent and deconstruct South-east Asian cuisine into fine dining – and that seemed like a natural partnership with the premium water that I supply and curate,” explains Mr Wu.

Despite these crucial alliances and partnerships, Mr Wu, who is single, admits that he still has a long way to go. “It’s a tough business. My pay cheque is very minimal and doesn’t even amount to a typical fresh graduate’s pay. But I’ve reached a point where I can say that I’m not bleeding out, that the business is sustainable and that I am able to grow my team to include four of us in total,” he says.

More importantly, he adds: “I get to do something I love and which is meaningful. Hopefully, I can help more people appreciate water as a beverage and all its complexities.”