Newly discovered origami patterns put the bloom on the fold

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

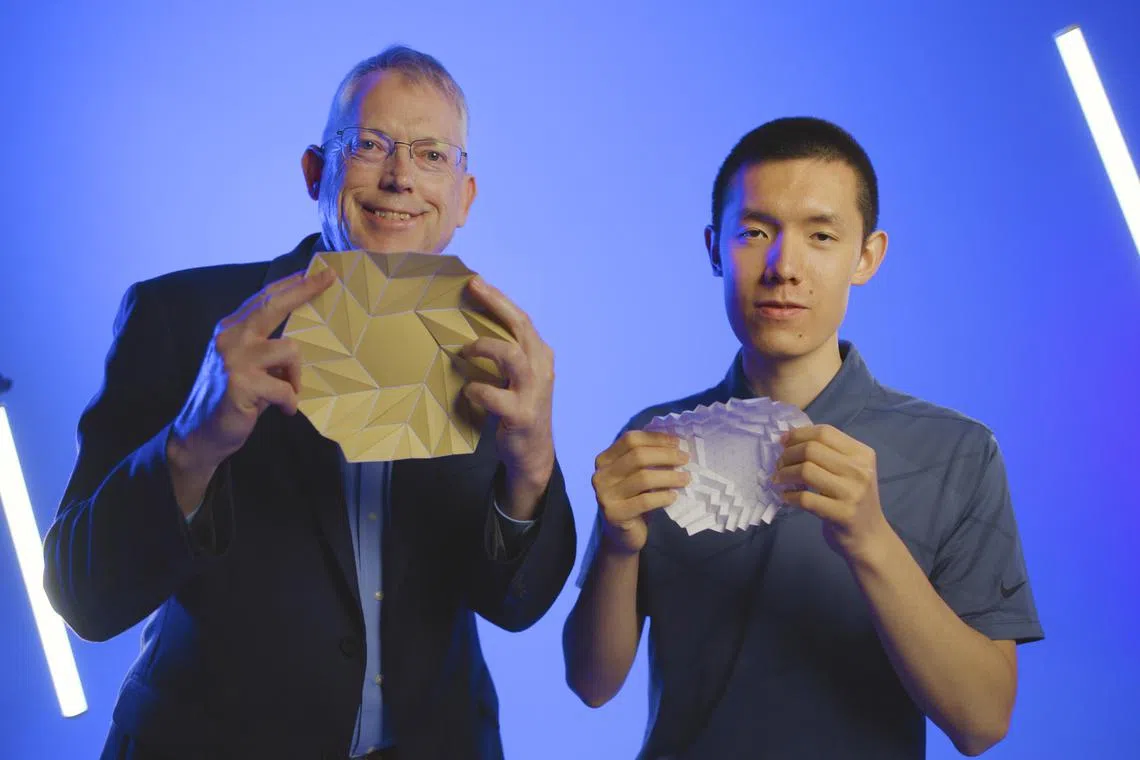

Brigham Young University's Prof Larry Howell and Mr Wang Zhongyuan with some of the origami designs.

PHOTO: BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY

NEW YORK – The art of origami goes back centuries – enough time to explore every possible crease that can be made in a sheet of paper, one might think.

And yet, researchers have now found a new class of origami that they call bloom patterns. Resembling idealised flowers, many bloom patterns are rotationally symmetric around the centre.

The bloom patterns, with their set of attractive properties, appear promising for future engineering uses, especially for large structures that are sent to outer space. They fold up flat and compactly, they can be constructed out of one flat sheet, and they can be extended to ever larger shapes.

The discoveries originated from the paper-folding explorations of Mr Wang Zhongyuan, a sophomore at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Utah.

“I love to do origami, but if I can use origami to make practical applications that benefit the world, that will be a dream come true,” he said in a video produced by BYU.

Mr Wang, with Professor Larry Howell from BYU’s department of mechanical engineering, and Robert Lang, an origami artist and theorist who lives in Pasadena, California, reported their findings in a paper published recently in the journal Proceedings Of The Royal Society A.

The researchers have also provided an archive of images, videos and other help for anyone wishing to fold their own bloom patterns.

A photo provided by Brigham Young University shows an origami piece with bloom patterns.

PHOTO: BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY

Lang said the biggest novelty here is that the bloom patterns fold flat.

Origami artists have long used patterns that they call “flashers”, which are also radially symmetric and expandable. But in their folded configuration, flashers are cylindrical, not flat. Other rotationally symmetric origami patterns – including one called a simple flat twist – fold flat, but cannot be readily extended to larger sizes.

In an e-mail, Mr Wang said he started folding origami when he was eight or nine years old, growing up in Beijing. Then, he followed online tutorials. In his explorations, he folded a few bloom patterns centred on a hexagonal base.

“At that time, I was trying a lot of new patterns. It wasn’t until several years later that I recognised that these patterns are truly special.”

Browsing videos on YouTube, he learnt about Prof Howell and his work turning origami into applications he never imagined, Mr Wang said. Prof Howell, for instance, is working with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration on an origami design for a future space telescope.

Mr Wang applied to BYU to join Prof Howell’s research group.

Lang visited Prof Howell’s laboratory in December 2024 and met Mr Wang and the bloom pattern for the first time. Lang told Mr Wang: “I don’t recall seeing something like this before.”

Lang said Mr Wang had found this elegant way of not just scaling a simple flat twist, but developing an entire family of these things. “This is a very pleasant surprise.”

The bloom patterns can be broken down into repeating tiles of creased patterns, called wedges, around a central polygon. Larger structures, which can still be folded flat, are created by expanding the wedges into larger shapes with additional creases. When folded, the wedges stack up in a helical shape.

Prof Howell said a search through the scientific literature turned up a few individual bloom patterns that had been folded previously, but the new paper provides a general mathematical framework that describes a new class of possible foldings.

“It has basically an infinite number of origami patterns,” he said.

Professor Tomohiro Tachi from the University of Tokyo and an origami expert who was not involved with the research, said: “Their key contribution lies in providing a generalisable method for generating these patterns.”

That increases the repertoire of origami designs available to scientists, engineers and designers, Prof Tachi said.

Prof Howell’s research group has made physical manifestations of the bloom patterns, not just out of paper, but also from other materials like 3D-printed plastics.

Real-world applications, like solar panels, will not be as thin as paper, and the folds may need to be wider to accommodate the thickness of the tiles. Still, the fundamental flat-folding nature of bloom patterns means it should be easier to pack a structure into the limited space of a rocket.

Lang added that the advances are not just practical but aesthetic. He pointed out a bowl-shaped pattern by Mr Wang, with its sides curving upwards like an intricate vase.

“The real folded thing – he’s actually folded those – is really beautiful,” Lang said. “I would not be surprised to see that in a museum.” NYTIMES