World may not be as ready for electric vehicles as predicted

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

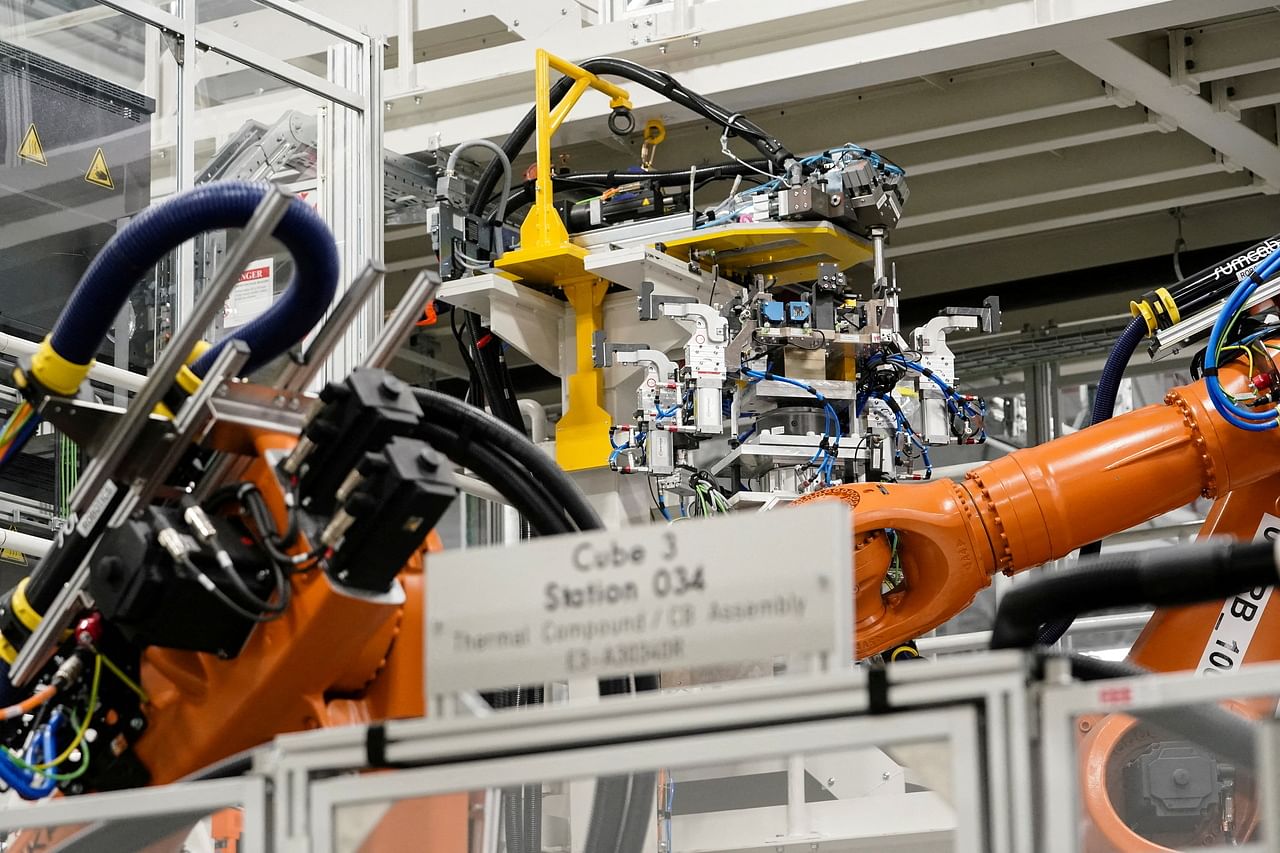

A looming issue for the industry is whether there will be enough battery manufacturing capacity to supply all manufacturers.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

NEW YORK (REUTERS) - The debate over how soon a significant share of individual car and truck buyers in the world's major car markets want to switch to an electric vehicle (EV) is supposed to be over.

But is it?

Let us start with Wall Street. Investors have gone cold on most EV company shares, slashing US$400 billion (S$557 billion) from the market caps of 10 leading EV start-ups in the past six months.

Of the combined market caps of those 10, Tesla makes up US$935 billion, or more than 90 per cent of the total. Rivian, with a market value of US$28.5 billion, accounts for more than 40 per cent of the remainder.

Rivian shares are down 69 per cent for the year to date, which makes General Motors' flat performance for the year look stellar. Remember when Detroit chief executives wanted to be valued like tech companies? Not so much anymore.

Investors are reacting to a wide range of factors, including the end of free money from the United States Federal Reserve. But there are a lot of questions about how ready the world and the battery vehicle industry are to have half or more new vehicles sold be electric by 2030.

A looming issue for the EV industry is whether there will be enough battery manufacturing capacity to supply all the vehicles manufacturers intend to build by the end of the decade.

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a consultancy which tracks global battery capacity and raw materials supplies in detail, sees a nearly 9 per cent shortfall in battery production versus EV demand by 2030.

The good news for EV manufacturers is that between now and 2025, Benchmark forecasts EV battery-makers will have more than enough capacity to supply projected EV production. The next five years are less certain.

Benchmark senior analyst Aran Waid cautions that it can take two to five years for a new battery plant to produce at 80 to 85 per cent capacity, and mature plants in China can still run at as low as 65 per cent capacity.

This is why car industry executives are scrambling to lock in battery-supply deals, and why governments - including the United States Joe Biden administration - are prepared to subsidise battery production and supply-chain development.

This week, the Biden administration kicked off a roadshow to encourage US battery-manufacturing companies to apply for more than US$3 billion in Energy Department grants aimed at amplifying private investment in battery manufacturing and related activities, though not raw material mining.

The details of the programme are not set and the short-term impact will be minimal - if you set aside the potential political benefits of promoting EV jobs in the Midwest ahead of the mid-term elections.

"It's a step towards the White House's goal for half of vehicle sales to be electric by 2030, but it will take years for the effect to impact the vehicle industry," said Ms Lisa Whalen, an auto and mobility analyst at Morning Consult.

Many companies will compete for the federal money. The US car sector's anxiety about depending on China for battery materials could lift start-ups that want to create North American-based battery manufacturing capacity.

Separately, Seattle start-up Group14 Technologies landed US$400 million in fresh capital from a group led by Porsche to develop its silicon anode technology.

It is not just Washington that is giving the American EV industry a helping hand. Georgia has promised US$1.5 billion in subsidies to Rivian's proposed EV manufacturing complex there. The authorities in Shanghai sent workers to help Tesla restart its factory there after a Covid-19 shutdown.

Batteries and assembly plants are important, but adequate production capacity alone does not assure that markets are ready for a mass switch to electric vehicles.

Machines are seen on a battery tray assembly line in Woodstock, Alabama, on March 15, 2022.

PHOTO: X03421

LeasePlan, a company that manages 1.8 million vehicles globally, has done a new study on how ready US states are to support substantial EV fleets. It has concluded none of them are.

LeasePlan said it looked at the ratio of EVs to public chargers, availability of public chargers, level of state incentives, current market shares for electric vehicles and climate suitability, which means how cold a place can get.

On those measures, it found that the best-prepared states are Nevada, Mississippi and Hawaii. That may come as a surprise to California, the US state with by far the highest market share of EVs at 12.5 per cent, according to US Energy Department data.

To put things in perspective, California's EV share is nothing compared with Norway's, where 65 per cent of all vehicles sold last year were fully electric.

But it is ahead of Singapore, where 8 per cent of new cars sold in the first quarter of 2022 were EVs. And according to consulting firm McKinsey, EVs made up 2.5 per cent of all light vehicles sold around the world in 2019.