F1: Come for the drama, stay for the superhuman display of grit and precision

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

![ST20251002_202591100704 Azmi Athni saf103//

The Straits Times writer Sarah Koh poses in front of the BWT Alpine F1 Team garage at the Singapore circuit on Thursday, Oct 2, 2025.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

[NOTE: F1 photos are for editorial use only and NOT for sale.]](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/straitstimes/65fa0aaa1304f470b275bf36da8fe60855a5aa0238d973592792ca3b8be00f3d)

ST writer Sarah Koh poses beside a front wing belonging to the BWT Alpine Formula One Team, at the team's garage at the Marina Bay Street Circuit on Oct 2.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Not everyone wants to give up his or her life for work. As a 26-year-old, I have lost count of how many times the term “work-life balance” has escaped my mouth while chatting with peers in their 20s.

But for 29-year-old Formula One (F1) driver Pierre Gasly, compromising on his career that he has spent every waking hour of his life working towards is simply unthinkable. He is one of two drivers for the BWT Alpine Formula One Team.

Closing in on his 10th year in F1, he would likely not be judged harshly if he retired without winning a championship. But during a media roundtable held at the Marina Bay Street Circuit on Oct 2, ahead of the F1 Singapore Airlines Singapore Grand Prix race weekend, he adamantly declares he wants to be world champion, even if it means having to make personal sacrifices.

With more than 20 races a season, running from March to December, endless training on the driving simulator and media engagements, he has not spent more than 50 days back home in Milan, Italy, in a year. Those precious few days are spent with his family, friends, girlfriend – and on even more training.

“It’s a balance you need to find – some people understand it and support you along the way, and some people won’t understand why you don’t have time to give them, and then you lose people along the way,” says Gasly, who is 16th in the drivers’ standings.

“But I’m not someone willing to compromise on my professional life. I told all my friends that the day I finish F1, every single day I can be at your door at 8am knocking and saying, ‘Let’s grab a drink.’

“But don’t ask me to do that when I’m in the middle of my career,” he adds, with steely determination.

The racing team, which is based in Enstone, England, arrives at the Singapore Grand Prix at the back of the standing, behind nine other race teams which are just as driven to perform.

As a relatively new fan of the sport, I am in part drawn in by the heavy advertising in mainstream consciousness. Content such as Netflix docuseries F1: Drive To Survive (2019 to present) that gives viewers a behind-the-scenes look into F1, and motor racing no longer feels stuffy, but sexy.

Where the sport might have used to be seen as one that is enjoyed only by the wealthy, the increased exposure has helped to humanise it and the drivers.

But as I sit in the wake of Gasly’s response during a three-hour visit to the paddock on Oct 2, I realise that beneath the polished and glitzy exterior, the sport is a lifestyle that demands a superhuman level of discipline and grit.

It is the same for fellow driver and teammate Franco Colapinto. For a 22-year-old, he strikes a solemn vibe.

“When I sit in the car and start driving, it’s a moment I’ve always dreamt of since I was very little,” says the Argentinian.

All work and no play for now: BWT F1 team drivers Pierre Gasly (left) and Franco Colapinto talking about the sacrifices they’ve made for their racing career.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

“I left my country when I was 13 and I went without my family to live in a (racing team’s) factory. That’s what it takes to achieve your dream. But this also gives me extra motivation when difficult times come, because you know how much it took to arrive where you want to be.”

Hearing about this from anyone else on a regular day would be remarkable, but such stories tend to get lost in the noise when it comes to F1, which often presents itself publicly in the form of countless brand deals and a relentless chase for more speed, specs and sponsors.

And while the spotlight is mostly on the drivers, also much less talked about is the quiet commitment that everyone else in the grid possesses.

During my visit to the paddock and the Alpine F1 team’s garage, I thought I knew what to expect after three years of watching the sport – shiny cars, screaming fans waiting outside to catch a glimpse of their favourite drivers and rich people doing rich people things.

While I do see a handful of engineers and mechanics milling around and fiddling with car parts, as is often seen on TV, putting on a good show takes much more than that, says Alpine’s head of technical and integrated partnerships Ian Goddard.

Head of technical and integrated partnerships at BWT Alpine F1 team, Ian Goddard, giving a rundown of the team’s garage at the Marina Bay Street Circuit on Oct 2.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

Around 1,000 employees, to be specific, and that is just from one of the 10 teams on the grid. Though most are based in the Enstone Technical Centre back in Britain, about 100 of them travel around the world to the races.

Of these, 60 are engineers and technicians who mostly attend all the races in a year, says Mr Goddard. Probably without the multi-million-dollar pay packages and fame of the drivers, I think, as I watch them crawl under the cars, lug bulky car parts around and wield large tyres that look smaller on TV.

“Each of them weighs around 23kg,” says Mr Goddard with a smile, to my shock. After all, when the cars usually come in for a pit stop twice during a race, a team of 12 mechanics often makes it look like an effortless endeavour to change four tyres at breakneck speed.

The record for the fastest pit stop in 2025 so far is 1.91 seconds by the McLaren pit crew during the Italian Grand Prix. I am pretty sure I’ve had sneezes that lasted longer.

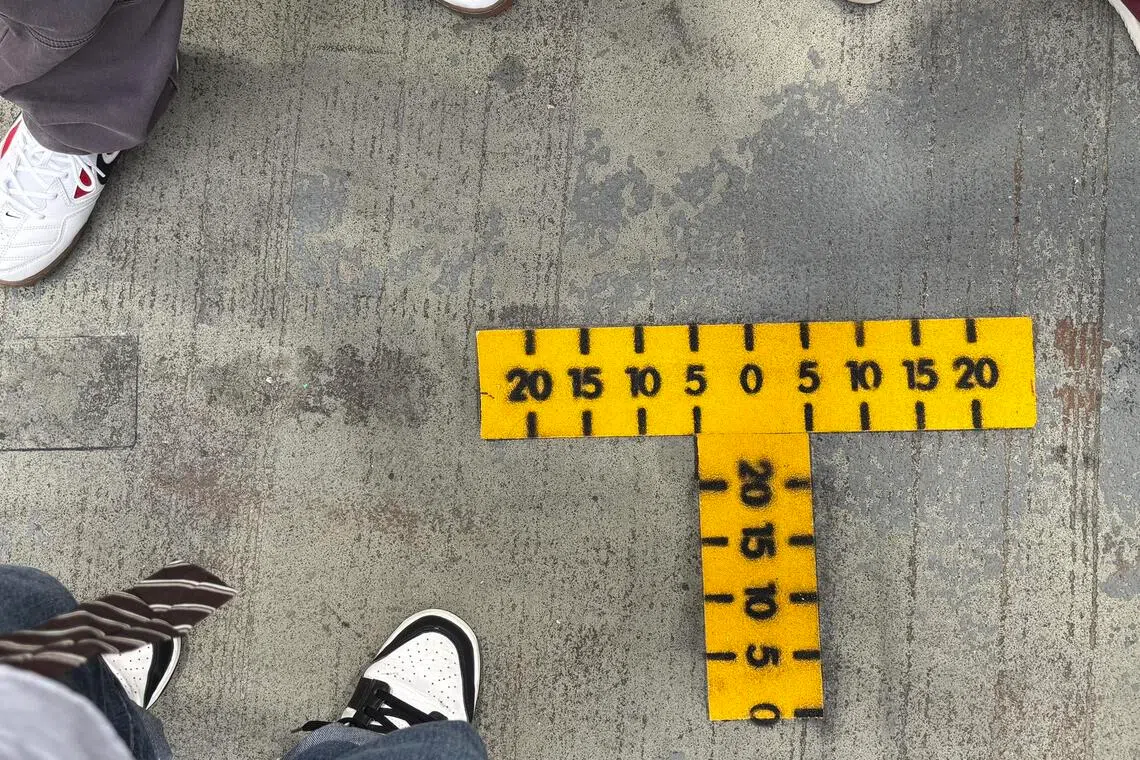

As I revel in the loud engine sounds going off and the strong smell of fuel, Mr Goddard directs our attention towards a 40cm-long yellow marking on the ground – small enough to go unnoticed by TV cameras.

He points out that as the cars come down the pit lane at anywhere between 60kmh and 80kmh, as stipulated by the race organiser, the driver needs to stop the car precisely within the markings, where mechanics crouch waiting to change out the tyres.

Drivers are expected to line up their tyres exactly against a 40cm-long yellow marking on the ground.

ST PHOTO: SARAH KOH

Even a slight deviation by a few centimetres by the driver would potentially mean piling on precious seconds, which in F1 speak, could very well decide whether a driver remains in contention for the championship.

What initially appears unremarkable turns out to be a perfect example of the extreme level of precision required to succeed in the sport.

As a journalist, I relish these bits of lore. But as a fan, it makes me rethink the way I view the sport. The number of times I have sat on the couch scoffing at any pit stop that lasts more than 2½ seconds makes me slightly ashamed to be anywhere near the team.

From one’s home, it is easy to take for granted the spectacle that flashes across the TV screen. Lap times down to the thousandths of a second are recorded and viewers are somehow able to hear what the drivers are saying as they barrel down the track in excess of 300kmh.

Nothing is left to chance in this sport. Situated in the cars and around each track sit 150 microphones and around 140 cameras, which help to collect 600TB of data each race day, the equivalent of 200 million songs.

The scale of hardware required to carry this data is also massive, with more than 600 F1 employees using Lenovo laptops, tablets, monitors, workstations, servers and Motorola smartphones on track to power a smooth broadcast for millions of viewers globally.

Such trackside devices are made to withstand the various weather conditions across the world, whether it is Singapore’s high humidity or 50 deg C temperature in the Middle East, says Mr Sumir Bhatia, Lenovo’s president of infrastructure solutions group in Asia-Pacific.

He adds: “Just three years ago, we were talking about data in 200 or 300TB. As fan experiences continue to grow, I can guarantee that by next year, we’ll be talking 800 to 900TB.”

I got into the sport partially due to the wild success of Drive To Survive, which has catapulted the sport into an entertainment reality show that highlights explosive moments such as dramatic arguments between drivers or team principals, and high-speed crashes.

But in the past three years, I have at times pondered whether my interest in F1 is considered performative if I do not have a deep appreciation of cars or if I could not list 10 world champions without Googling it.

However, this opportunity to see the sport in action up close shows me the true value of F1 to the viewer – the dedication from every side of the grid to pushing the boundaries of human possibility.

I do not know if I can commit to being a world-class racing driver one day, but maybe I will start by agreeing to get that driver’s licence my parents have been hounding me about.