Are electric vehicles really greener?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

At the point of production, EVs have a larger carbon footprint than ICE cars.

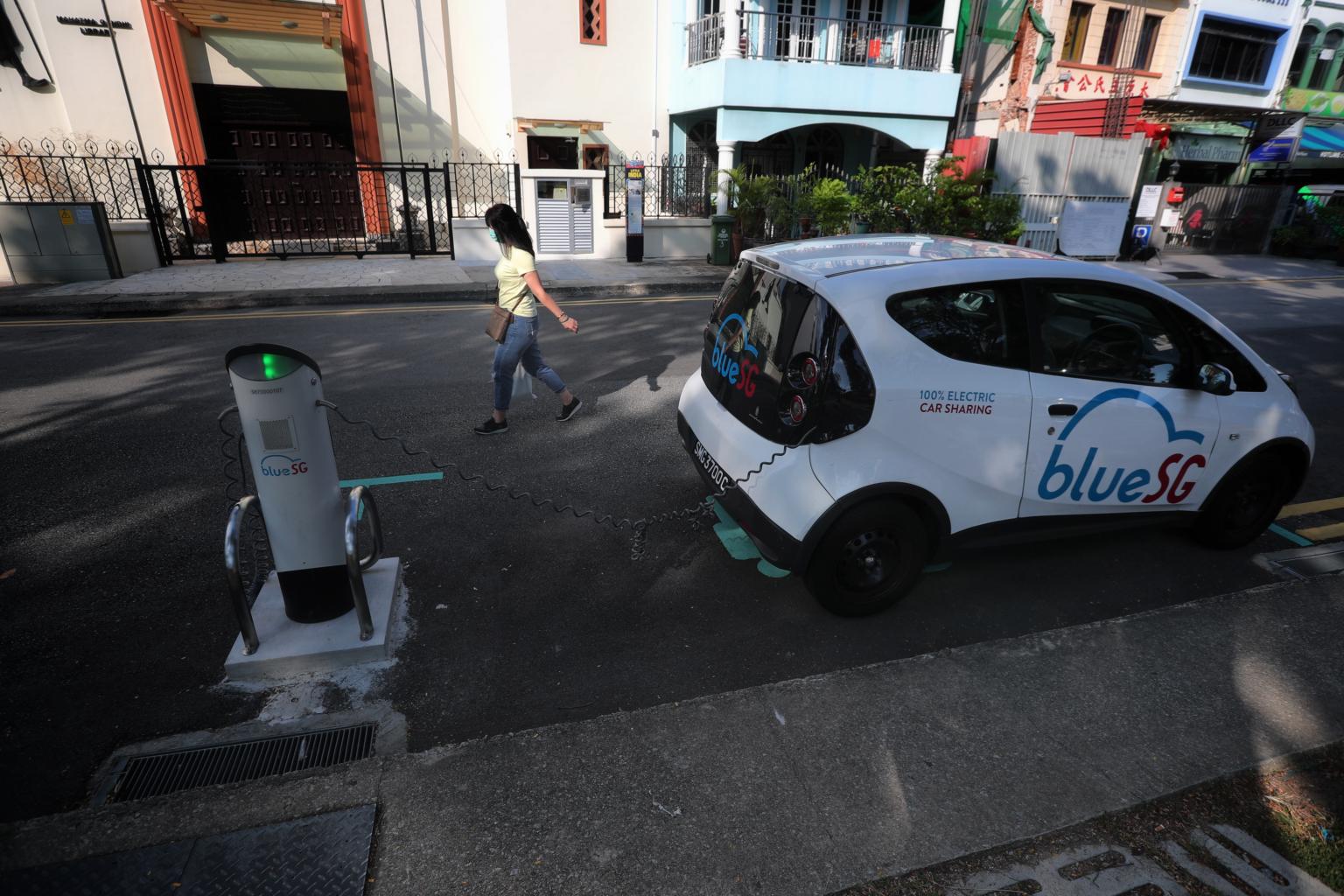

PHOTO: ST FILE

SINGAPORE - Electric vehicles (EVs) are cleaner and quieter where they matter - in densely built-up areas where there is close interaction between vehicles and people.

But what about on the whole? Are EVs really better for the environment when you take into account things like power generation and manufacturing processes?

You might have heard differing views, with some asserting that EVs are no better, or even worse, than equivalents driven by internal combustion engines (ICE).

Well, the Wall Street Journal commissioned the University of Toronto to get to the bottom of the issue. And the findings, released in March, are surprising.

At the point of production, EVs have a larger carbon footprint than ICE cars. This is mostly because lithium-ion batteries are rather resource-intensive.

To be precise, a mid-sized electric sedan emits 12.2 tonnes of CO2 when produced, compared with 7.4 tonnes for an ICE rival.

After about 8,000km of use, the EV emits 12.8 tonnes of CO2, compared with 9.2 from the ICE car.

And at the 16,500km mark - clocked annually by the average family car in Singapore - the EV is responsible for 13.4 tonnes of carbon, versus 11 tonnes by the ICE vehicle.

The two reach parity at around 33,300km, or double what the average family car clocks here.

And at 49,500km - a distance clocked each year by many taxis and private-hire cars - the EV pulls ahead with 15.9 tonnes of CO2, versus the ICE's 18.3 tonnes.

By 165,000km - the distance clocked by the average family car over 10 years - the EV is responsible for 24.4 tonnes of CO2, versus 43.6 tonnes by the ICE rival.

The study also found that for the United States to meet goals set in the Paris Agreement, all cars will have to be electric by 2035.

Is that the only way to limit global temperatures from rising by more than 2 deg C in this century? Actually, the study found that going full electric is not the only way.

An alternative would be to promote EVs alongside strategies such as reducing vehicle size and weight, improving efficiency and cutting down on mileage clocked.

In Singapore, converting all light vehicles to electric propulsion would result in a reduction of 1.5 million to two million tonnes in emissions per year, former Transport Minister Ong Ye Kung said last month.

This translates to a reduction of just around 4 per cent of Singapore's total emissions.

While not insignificant, it is not a huge figure. This is because heavy vehicles such as lorries and buses contribute significantly to emissions.

If these vehicles can run on battery power, the nationwide reduction in emissions would be larger.

Industries remain the largest contributor to emissions here, with one of the biggest culprits being the petrochemical sector. The country's constant drive for urban renewal is also responsible.

Hence, for a double-digit reduction in emissions, Singapore must wean itself off oil-based industries and adopt a longer-term strategy in land use and urban redevelopment.

As for the University of Toronto study, there was no mention of issues such as battery degradation and battery recycling.

Today's ICE vehicles are highly recyclable, but the recycling of EVs is still at its early stages.

Battery degradation is another issue which requires a closer look.

If an EV's battery has to be replaced once in its lifetime, the resources and emissions involved will be substantially higher than the figures arrived at by the university.

This is another reason battery-swopping schemes should not be encouraged. They are resource-intensive, requiring up to two batteries a vehicle on the road.

The way to go is still to roll out a comprehensive and affordable charging network. If charging is costly or inconvenient, motorists are likely to stick to or revert to ICE cars.

A study by the University of California in April found that around a fifth of EV owners in California - seen to be the most EV-friendly state in the US - had gone back to ICE cars because they found charging to be inconvenient.

On this front, Singapore's aim to have 60,000 public charging points by 2030 is encouraging.

But average charging rates have to come down. They are currently nearly double the household electricity rate, making it uneconomical for EV owners who do not have access to home-based charging.

If we are really serious about converting a huge portion of our cars to electric, this has to change.