Japan’s sake-making up for Unesco Heritage bid even as domestic market shrinks

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Vintage sake pairing with Japanese cuisine.

PHOTO: PASONA GROUP

TOKYO – Japan’s sake breweries are staring down the threat of declining demand at home as consumer preferences shift to other alcoholic beverages like beer and wine – if they are still drinking at all, with teetotalism rising among a health-conscious population.

In response, some breweries are aiming to alter perceptions of sake as a cheap, quotidian alcoholic beverage by positioning it as a more premium option.

The upside, however, is the growing attention and demand for Japanese sake abroad.

Moreover, Japan has put up a bid to recognise traditional sake-making techniques using koji mould – which converts starch in the ingredients into sugar – as Unesco Intangible Cultural Heritage, with a decision due in December.

“Traditional knowledge and skills of sake-making have been developed through the accumulation of experience by chief sake makers (toji) and sake brewery workers (kurabito) since before the establishment and spread of modern science, and have been built up as a manual process,” Japan said in its Unesco bid documents.

“These knowledge and skills have been handed down in various regions of Japan in various forms according to the local climate and environment,” it added, noting that Japanese alcohol production is essential to various aspects of everyday life, culture and rituals from funerals to celebrations.

The term Japanese “sake” in English often refers to the alcoholic beverage brewed from fermented rice, which is also known as nihonshu or seishu in Japanese.

But the term “sake” in Japanese may also be a catch-all for Japanese liquor in general, including shochu (distilled alcohol), awamori (a distilled alcohol native to Okinawa) and mirin (a rice wine commonly used in cooking).

The domestic market for Japanese sake has been shrinking. In 2023, the domestic sake consignment stood at just 390,000 kilolitres, about a fifth of its peak in 1973 when 1.7 million kilolitres were shipped within Japan.

At the same time, the number of active sake brewery licences in Japan has plunged by more than half, from 3,533 in 1970 to 1,544 in 2023, according to National Tax Agency data.

It is in this environment that some sake breweries are trying to create new value by resurrecting the long-lost tradition of maturing sake – “ageing like fine sake” may well be the new “ageing like fine wine”.

Vintage sake, known as koshu in Japanese, was for centuries the beverage of choice for aristocrats since at least the Kamakura Period (1185-1333) until the early years of the Meiji Era beginning in 1868, when the practice of ageing sake was phased out.

Others like Asahi Shuzo, which produces one of Japan’s most famous sake brands Dassai, are trying to capture a bigger slice of the burgeoning overseas market.

In 2023, Asahi Shuzo opened a brewery in New York to produce Dassai Blue sake, which in April 2024 was reverse-imported back into Japan for the first time, in a limited-time campaign.

Sake and wine differ in how they are produced – the former from rice and the latter from grapes – but both are sophisticated fermented alcoholic beverages that sommeliers and restaurateurs say can vastly elevate the fine dining experience.

Look no further than to how Japanese sake is increasingly being featured in fine dining menus across Japanese kaiseki and French haute cuisine, as a testament to both cuisines’ affinity.

This drive to reinvent sake as an upmarket premium product is evident in how the proportion of quality-grade sake, which includes the highest-class junmai-daiginjo, distributed in Japan increased from 26 per cent in 1998 to 37 per cent in 2023, according to agriculture ministry data.

Further fuelling demand are growing sake exports in tangent with the rise in Japanese soft power, surging from 8,000 kilolitres in 1998 to a record 36,000 kilolitres in 2022, with a total value of 47.5 billion yen (S$410 million).

This dipped slightly to 29,000 kilolitres worth 41.1 billion yen in 2023 as the post-pandemic surge in demand tapered off, although stakeholders expect the export market to grow even further as more foreigners are exposed to Japanese sake amid the tourism boom.

It is in this climate that Asahi Shuzo – based in Iwakuni in Yamaguchi prefecture – is expanding its horizons, leveraging on the name recognition of Dassai, which regularly features on the menu at leaders’ summits in Japan.

Asahi Shuzo is the first Japanese sake brewery to launch on the East Coast of the United States, even as there are others on the West Coast, such as an outpost of Kyoto-based Gekkeikan that use California-grown short-grain rice.

Its 5,110 sq m brewery in Hyde Park (5 St Andrews Road, Hyde Park, New York; go to dassai.com

Asahi Shuzo’s sake brewery in New York produces Dassai Blue sake.

PHOTO: ASAHI SHUZO

Dassai Blue is made using water from New York’s Hudson Valley and – like in Japan – premium Yamada Nishiki short-grain rice that Asahi Shuzo is working with US farmers to grow. The first batch of Dassai Blue was released in New York on Sept 25, 2023.

“We want to expand the presence of sake in an important market and grow its value as a high-quality premium alcoholic beverage,” fourth-generation president Kazuhiro Sakurai, 48, says.

“Japanese sake accounts for only 0.2 per cent of the total alcoholic beverage consumption in the US, and we want to take on the challenge of growing its share.”

Asahi Shuzo has long embodied the spirit of breaking new ground, including a one-time collaboration with the late acclaimed chef Joel Robuchon on the Dassai Joel Robuchon restaurant in Paris.

It has already once found success by going upmarket. In the 1980s, as the firm was struggling, it pivoted towards exclusively producing the highest quality junmai-daiginjo, in a decision that has paid off handsomely.

Asahi Shuzo had been an industry pioneer in practices such as year-round brewing, and in polishing rice down to 23 per cent as compared with the industry norms at the time of 50 per cent.

Now, in setting its sights on the US, it has invested 8.5 billion yen into the Hyde Park brewery, which has an annual capacity of up to 140,000 cases of Dassai Blue sake, at nine litres a case.

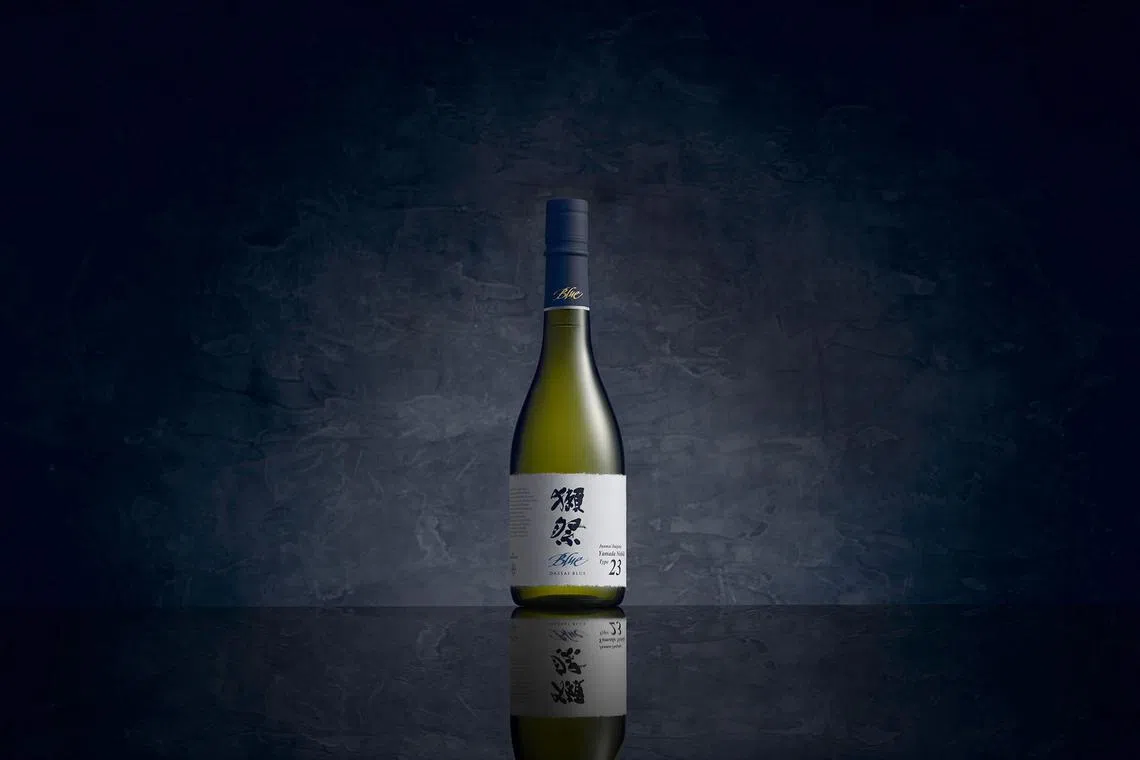

There are two types of Dassai Blue: Type 23, with rice polished down to 23 per cent, and Type 50, with rice polished down to 50 per cent.

Dassai Blue Type 23. Asahi Shuzo’s president Kazuhiro Sakurai hopes New York-made Dassai Blue can one day surpass the Dassai produced at its Japan brewery.

PHOTO: ASAHI SHUZO

Mr Sakurai says the name Dassai Blue stems from a Japanese proverb about the indigo plant, whose dye has a deeper hue of blue than the plant from which it originates.

While he admits to challenges at the start, such as having to adjust to different levels of water hardness, he adds: “Instead of just trying to recreate the taste and aroma of Dassai that we make in Yamaguchi, we want to create the best possible sake in a new environment that can surpass the original Dassai.”

Asahi Shuzo is not in the vintage sake market, unlike some of its contemporaries that hope to revive the endangered heritage.

Maturing Japanese sake was once a common practice, though this petered out after the Meiji Revolution, when the then-government levied hefty taxes on alcohol makers.

The invention and proliferation of new technology allowed alcohol to be produced, bottled and distributed to market within a span of months, thus nurturing a new market for fresh sake.

At the same time, ageing sake required both time and space, which were luxuries that breweries and distilleries did not have amid the pressure to grow revenues to pay off taxes.

An unlikely advocate for the ongoing revival of vintage sake is human resources consultancy Pasona Group, which has invested in koshu through its subsidiary Takumi Sosei.

Takumi Sosei runs a flagship koshu speciality store and dining lounge Seikaiha Koshunoya on Awaji island (70 Nojimaokawa, Awaji, Hyogo; tel: +81-79-970-9111; speciality store opens 11am to 8pm; dining lounge opens 11.30am to 3pm and 5 to 9pm, except Thursdays; go to oldvintage.jp/en

There, visitors can sample koshu and savour meals made from fresh Awaji produce while gazing at the vast Seto Inland Sea.

A flight of vintage sake, dating to 2009, 2010 and 1984, at a restaurant on Awaji Island.

PHOTO: PASONA GROUP

It also has a store at Pasona’s headquarters in Minami-Aoyama in Tokyo (1F Pasona Square, 3-1-30 Minami-Aoyama, Minato-ku, Tokyo; tel: +81-36-832-7363; opens on weekdays from 10am to 5pm).

Matured sake has a fuller body and more luxuriously complex flavours than fresh sake, as the ageing process teases out sweetness, aroma and savoury umami.

“When you hear about vintage wine or mature whiskey, the image is that it must be very expensive,” says Takumi Sosei president Akihiko Yasumura. “But there is almost no market for aged sake in Japan.”

This market is something that Takumi Sosei hopes to create.

For a long time, the breweries that have persisted to produce vintage sake have gone at it virtually alone. Mr Yasumura hopes that having strength in numbers can help expand sales channels.

It now represents and distributes 88 brands of vintage alcoholic beverages, aged between 10 and 40 years, from 49 makers across 22 prefectures in Japan.

While most of its inventory is vintage nihonshu, it is also selling vintage shochu, awamori and umeshu (plum wine).

Furthermore, recognising that real estate, manpower and heavy maintenance costs are barriers for many small- and medium-sized breweries that are keen to age their products, Takumi Sosei has launched a joint alcohol storage facility that aims to create economies of scale.

A view of the storage facility for ageing sake, managed by Takumi Sosei.

PHOTO: PASONA GROUP

It is also working with breweries to produce a line of blended vintage sake under the label Inishie.

All these efforts come as the attention on vintage alcohol is clearly growing, Mr Yasumura says, adding that the time is ripe to increase public awareness and expand distribution channels both locally and abroad.

At the Singapore Sake Awards in 2023, two brands of umeshu made in 2009 – Bunzo, made in Kumamoto, and Matsufuji, made in Okinawa – took home the Platinum prize. So did 2007 Sanin Togo sake, which was brewed in Tottori. Aoitsuru sake, made in 1995, won the Bronze award. Results for 2024 are due on Nov 6.

Vintage sake has increasingly found a place on pairing menus in Japan, including at one-Michelin-starred Agnel D’Or in Osaka (2 Chome-4-4 Nishihonmachi, Nishi-ku, Osaka; tel: +81-64-981-1974; agneldor.com sakematured.com/en

Okada Honke in Hyogo prefecture is among the breweries working with Takumi Sosei. Founded in 1874, it produces the Seiten range of sake.

Sixth-generation president Yoichi Okada says: “Unlike junmai-daiginjo, it will take 10 years to mature a batch of vintage sake. We are now only at the starting line, but we want to produce a lot in anticipation of future demand.”

He adds: “I hope more people will know about matured sake and will get to savour it.”