It’s always election season somewhere in Singapore: Inside HDB’s colour democracy

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Every day, residents across Singapore are casting their vote on municipal-level issues like flat repainting.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

SINGAPORE – When the residents of a Teck Whye Avenue housing estate went to the polls in 2017, they were not choosing political candidates or parties.

They were deciding on whether the exterior of their flats should be repainted in a Mondrian-inspired red, white, blue and yellow scheme or something more conventional.

The unusual choice claimed a landslide victory.

The design inspired by Dutch abstract artist Piet Mondrian won 75 per cent of the votes in the seven blocks that make up the Housing Board estate, beating two alternatives.

It was an outcome lauded by both residents and netizens at the time.

Mr Dhaval Bhate, a 36-year-old former resident of the estate, says the striking colours added to Teck Whye’s uniqueness. The estate’s 25-storey seventh block was among the tallest HDB flats in the west of Singapore at the time.

“One often needs to read the road signs just to know where you are in Singapore because most HDB blocks look almost the same, whether it’s Bedok or Clementi,” says the tech start-up worker, a “perpetual renter” who has moved house 13 times in 19 years.

“But that’s the thing about those Teck Whye blocks. They stood out, they really had character.”

What happened in Teck Whye happens almost every day in Singapore. Over 77 per cent of the island’s resident population live in public housing blocks, which are typically repainted every seven years.

This everyday democratic exercise has become a distinctive feature of urban life in the Republic.

When purple goes wrong

Some Tiong Bahru residents were upset by the purple scheme used in the repainting of their block.

ST PHOTO: TARYN NG

The stakes of these consultations bubbled to the surface during a public spat at an HDB estate in Tiong Bahru in May.

Some residents expressed anger over a block in Boon Tiong Road being repainted a “gaudy” purple without a vote.

This prompted an intervention from Mr Foo Cexiang, a newly elected Member of Parliament, to organise a vote. He is an MP for the Tanjong Pagar GRC and oversees the estate’s Boon Tiong area.

The vote, held over three days in May, resulted in 40 per cent opting for a brown scheme.

“More than 200 residents of Boon Tiong took the time to attend our town hall sessions, and more than 550 households participated in the voting, showing how invested residents are in shaping their neighbourhood together,” Mr Foo tells The Straits Times.

He notes that there is no protocol on how the repainting process should be conducted.

“From my recent experience, such consultations can strengthen the community spirit and deepen a sense of belonging,” he adds.

A “colour scheme survey form” box outside the Boon Tiong RC Centre.

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

According to experts, this clamour around flat colours reflects a broader trend towards participatory governance.

Referring to the backlash sparked by the Tiong Bahru purple-paint episode, Nanyang Technological University lecturer Felix Tan says: “I believe that this episode demonstrates how important participatory governance is to Singaporeans.”

The public policy lecturer adds: “There is a general expectation that citizens – and residents – should be given the opportunity to have a voice in such matters.”

Colour democracy in action

There is no standard playbook for colour consultations, says Dr George Wong, an assistant professor of sociology at Singapore Management University, who studies such municipal issues and grassroots organisations.

“But I don’t think it means there is no coordination or there is no consultation,” he adds.

ST contacted HDB for comment, but it declined.

In practice, the process varies widely across neighbourhoods.

For one thing, a vote is not always required. Dr Wong notes that in most neighbourhoods he has studied, there exists some kind of deliberative process – but the extent of residents’ involvement differs.

“In most cases, what MPs or grassroots advisers would do is at the very least include the residents’ network and grassroots leaders,” he adds.

While some MPs might believe it is important to understand what other residents think, others might be confident that their grassroots leaders know what residents want – especially if there is no feedback or complaint to indicate otherwise.

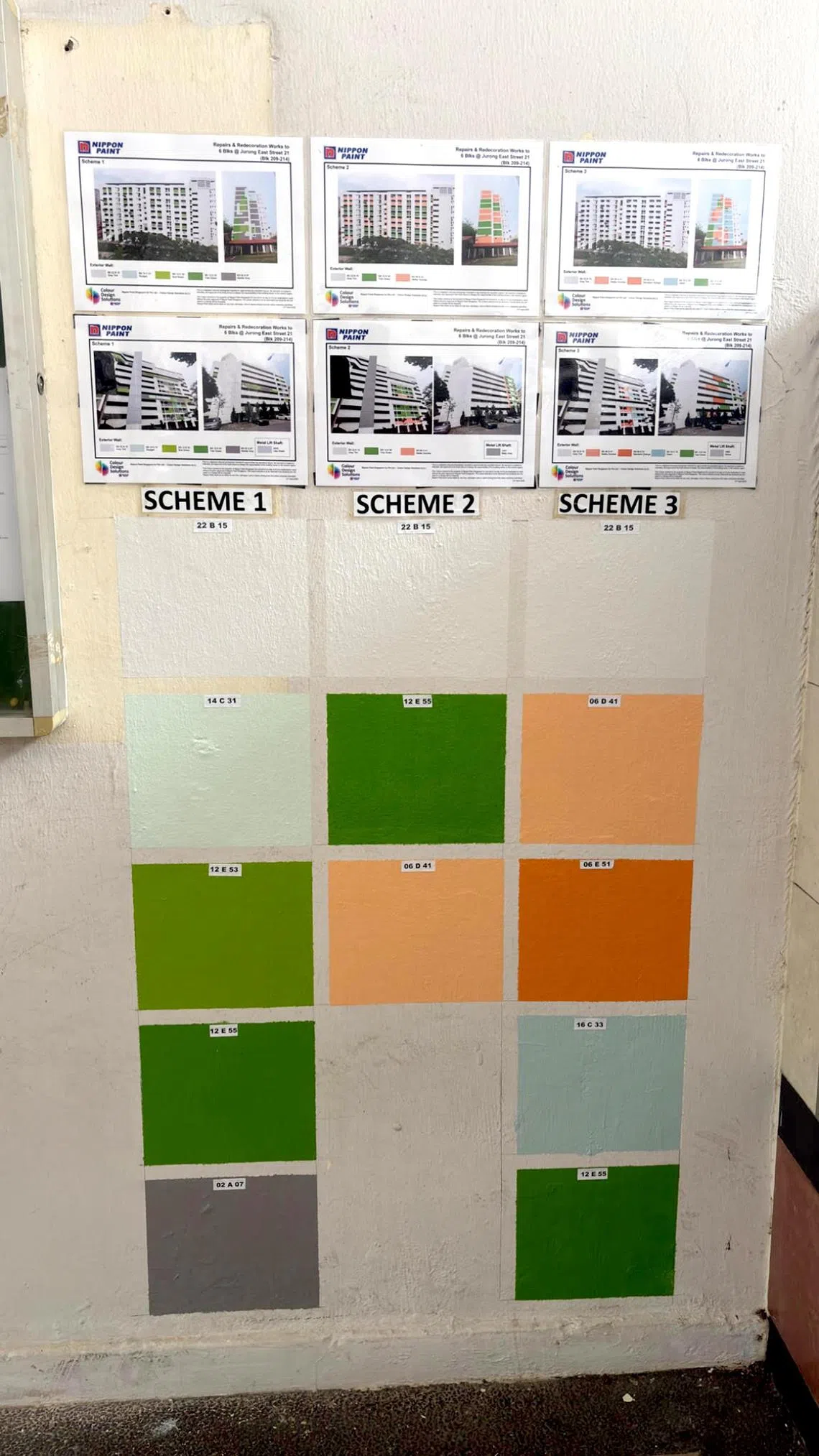

At this Jurong East HDB estate, residents could choose from three colour schemes.

PHOTO: DEVINDRAN JEYATHURAI

When votes do occur, the process varies widely.

Ms Mariel Loh, a 32-year-old research executive, says that during the consultation process at her Jurong West estate in 2023, around half of the residents voted.

ST reported in 2016 that the turnout rate of residents voting in such colour consultations was between 30 and 40 per cent.

Ms Loh voted for a maroon-grey scheme that lost to blue and yellow. “I’m appalled at my neighbours’ tastes,” she quips, though she admits the winning colours eventually grew on her.

“The colour options that we got weren’t exactly awesome. The other option was a hospital green combination that was dead last in the votes.”

While most residents speaking to ST are satisfied with the ease of voting – taking place either online or through physical ballots, depending on the neighbourhood – some complain about the limited choices on offer.

Depending on where they live, residents could pick from as few as two options or as many as four.

“I’m not crazy about the choices,” says Mr Devindran Jeyathurai, a 54-year-old polytechnic lecturer, about the consultation at his Jurong East housing estate in June. “It feels like these are the colours that Nippon Paint couldn’t sell.”

At this Tampines HDB estate, residents could pick between two colour schemes, with the current palette for comparison.

PHOTO: MATTHEW WEE

These are not trivial concerns.

Flat repainting may seem like a minor maintenance issue, but it plays a major role in shaping the visual character of neighbourhoods, says Dr Lee Kwan Ok, professor of real estate at NUS Business School.

In Singapore, public housing is not just a place to live, but also a defining element of the urban landscape. Repainting affects both the economic value of flats (through perceived upkeep and visual appeal) and their social value (as part of a shared community identity).

“Residents naturally care about how their blocks look – not only because they live there, but also because the aesthetics signal something about the status and cohesion of the community,” says Dr Lee.

“So, it makes sense that this process occasionally sparks outcry, especially if colour schemes feel imposed or disconnected from residents’ preferences.”

Why the differences in consultation?

Teck Whye Avenue’s distinctive look was the result of brainstorming and discussion between grassroots leaders and residents’ committees.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

According to Dr Wong, unevenness in how consultation is done across neighbourhoods results from three main factors: the MP or grassroots advisers, neighbourhood-specific legacies and the role of street-level bureaucrats.

Older neighbourhoods tend to have a greater interest in preserving an established aesthetic appearance, while neighbourhoods with younger populations are more open to unconventional designs.

Some MPs have a greater appetite for engaging residents. And civil servants from organisations with a local presence on the ground – such as HDB, National Environment Agency and National Parks Board – as well as town council property officers, also have some agency in shaping how stakeholders make sense of the consultation process.

In the case of Teck Whye’s multicoloured flats, the palette was the result of brainstorming and discussion by the town council, residents’ committees and paint specialists.

The area’s MP, then health minister Gan Kim Yong, told ST in 2018 he was “initially quite concerned” about the bold idea, “but since the residents were supportive in trying it out, I supported it and it turned out well”.

Towards participatory governance

ST PHOTO: SHINTARO TAY

While Singapore has traditionally taken a top-down approach to urban development, there is a growing recognition that everyday users of a space should have a voice in shaping it, says Dr Lee.

Flat repainting is one of the most visible examples, but there is a host of other micro-consultations taking place across Singapore today.

These include the public feedback process around transport signage

Though small in scale, these are signs of a larger movement towards a more responsive and participatory urban planning culture, says Dr Lee.

“It signals a recognition that design – whether at the scale of a building facade or a transport node – deeply influences lived experience.”

For another example of what this looks like in practice: Ang Mo Kio resident Mr Tan, who declined to give his first name, points to his estate voting on the installation of netting as a solution for high-rise littering, alongside a vote on colour schemes.

Such netting, installed on a building’s facade, prevents litter from being thrown onto a flat’s exterior ledges by residents on upper floors.

PHOTOS: ST READER

A majority of residents voted in favour in 2022. “After the washing, repainting and installing of the nets, the littering problem was eradicated completely,” says the 29-year-old transportation worker.

With a more educated population, there is a growing desire to have a say in matters that have direct and personal impact, says Dr Yeo Kang Shua, an associate professor of architectural history at Singapore University of Technology and Design.

An artist’s impression of an HDB estate. Under HDB’s Neighbourhood Renewal Programme, 17 projects across the island will get a $165 million facelift tailored to residents’ feedback.

PHOTO: A D LAB

This goes beyond municipal issues like sheltered walkways, and extends to broader, longer-term matters that influence Singapore’s built environment.

Dr Yeo believes increased public outreach has helped more Singaporeans recognise how the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s (URA) Master Plan may eventually shape their daily lives. He now observes more people attending the draft Master Plan exhibitions organised by the URA and submitting feedback.

Dr Wong says: “In the past 10 to 15 years, the Government has become more invested in co-creative processes. I see that happening a lot on the local level, different kinds of experimentations going on and different ways of deliberating with residents.”

“Ultimately, the political actors and street-level bureaucrats all want to find a sweet spot in which we can include both deliberation and decision-making,” he adds.

Finding the sweet spot

With participatory governance on the rise, why does dissatisfaction still occur?

One reason could be a perceived lack of agency. Some residents say that in their experience, consultations at the municipal level can feel like voting yes or no on predetermined plans.

Diversity of colour schemes on offer was a common complaint among residents speaking to ST.

PHOTO: ELLIOT NAPIER

“It seems like the town council already has something in mind and just implements it with regards to neighbourhood infrastructure matters,” says Jurong resident Ms Loh.

On the other hand, NUS researcher Matthew Wee, 29, is satisfied with the consultation process for the repainting of his Tampines HDB estate.

He notes that it might be impractical to offer residents more of a say without bogging down proceedings. “I think Singaporeans like to complain, but they are also quite forgetful,” he says.

Crucially, participation may not equate to empowerment. Dr Wong notes that consultation is not an end in itself, but a means of ensuring that stakeholders feel the process has taken shape in a way that allows them to feel they have agency.

Where this falls short can come down to Singapore’s “political culture of performance”. This means government agencies and grassroots bodies often feel they need to show they have done their work and research, and not present an “unfinished product”, says Dr Wong.

This often means 80 per cent of the work is complete by the time residents are invited to provide feedback. Discussions revolve around implementation, rather than ideation or more foundational aspects.

Dr Nikhil Joshi, a senior lecturer at NUS’ department of architecture, observes a similar trend in macro-level consultations.

He says public feedback is often sought for high-profile and medium- to large-scale projects like the Rail Corridor or the revitalisation of Kampong Glam – in ways that may not feel empowering to communities involved.

“Community empowerment and involvement from inception to launch make the project more sustainable than mere ‘consultation’,” he says.

Consultation nation or complaint nation?

These underlying tensions partly explain why discussions of municipality-level issues can seem so complaint-centric to the public.

Dr Wong notes that when things go well, the public will not hear of it. But when tensions spill over, complaints about municipal-level issues can go viral online and make national headlines.

This occurs partly because most Singaporeans know the appropriate channels for raising their concerns, especially when compared with local governments elsewhere.

“In Singapore, the locality of your MP is so reduced that you can – if not meet them during a Meet-the-People Session – e-mail them and likely get a reply in the next few days,” says Dr Wong.

Complaints are often the result of a breakdown in communication or an expression of frustration by groups who feel left out – and are usually met with a swift response by street-level bureaucrats and grassroots representatives.

MP Baey Yam Keng told ST in 2023 that the red scheme in this Tampines estate might not have been appropriate and asked HDB to look into it.

PHOTO: SHIN MIN DAILY NEWS

For instance, in 2023, complaints about the red-tiled lift lobbies at a Tampines Build-To-Order flat – described by some residents as “scary” – led to a repainting process to make the lift lobbies look more like those of other HDB flats.

Similar stories regarding frustrating street barriers unintuitive designs for covered walkways residents’ displeasure over paint

In Dr Wong’s view, harnessing the power of residents’ complaints has become an integral part of Singapore’s urban politics.

Outspoken local residents are often pulled into grassroots organisations, he observes. “Why do people end up becoming grassroots leaders? Often because they were complainers themselves in the first place.”

Technology also plays a role. A total of 1.7 million municipal-level complaints are made each year, according to the Ministry of National Development in 2023. Of these complaints, 38 per cent were made through the OneService app.

“If you think about it, who’s on the ground most of the time? It’s the residents,” says Dr Wong, who adds that the app has created a new social dynamic where citizen surveillance highlights potential blind spots.

“Residents feel empowered because their complaint is solved – which they can see in real time – and someone sends them an e-mail saying, ‘Thank you, you’ve been a great resident.’”

Yet, between complaints and consultations, there is the indifferent middle.

In Teck Whye Avenue, where the Mondrian-style experiment may soon reach an end, there is notable apathy among residents about the participatory process that created it.

A Chua Chu Kang Town Council spokesperson says four new colour schemes for the estate’s repainting are being shortlisted for a poll to be held in July. The current Mondrian style will be one of the options.

Teck Whye residents were not certain of their colourful block’s aesthetic future.

ST PHOTO: TEO KAI XIANG

While most long-time residents speaking to ST appreciate their estate’s distinctive style, most are unaware that it had resulted from a vote. Most are also unaware of what would replace it, seven years on.

Madam Rani, a 66-year-old retiree who has lived in the estate for 17 years, notes the area’s increasing wear and tear as a concern, but adds that she does not find it troubling enough to speak to her representative about it.

Another long-time resident, Irene, a 65-year-old retiree who declined to share her surname, expresses indifference about the process.

“It’s okay. I won’t say if I like or don’t like it,” she says. “I hope they do the repainting soon, though.”