New exhibition on old kampungs offers inspiration for modern architects

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The Lost Cities Series: Kampong Port Cities Of Pre-Colonial Era looks at how to create a comfortable microclimate without wasting precious natural resources.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

SINGAPORE – Around 700 years ago, before the rise of metropolises in South-east Asia, there were kampung port cities. These were built with organic materials, according to the principles of what is now known as “passive design”. The approach is guided by the local climate to maintain a comfortable temperature in the home.

This green urban design is the inspiration for The Lost Cities Series: Kampong Port Cities Of Pre-Colonial Era, a free exhibition which will run until Oct 1 at Fort Canning Centre.

It is jointly organised by multidisciplinary architectural practice The Oval Partnership in collaboration with numerous partners, including Associate Professor Johannes Widodo, director of graduate programmes in architectural conservation at the National University of Singapore (NUS), as well as student research groups from Singapore Management University (SMU) and Singapore Institute of Technology.

Mr Chris Law, co-founder of The Oval Partnership, came up with the idea for the initiative.

In line with his firm’s mission to study and preserve the region’s natural history, he says that it is conducting research with top institutions of higher learning and co-creating with communities where The Oval Partnership has a presence.

“Today, many people still see sustainable architecture as just solving the problem of carbon emissions,” says Mr Law, who co-founded The Oval Partnership in 1992 with Mr Patrick Bruce.

Besides Singapore, the international architecture and urban design practice has offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai and London.

The firm is known for its work on sustainable urbanism, community development and public space design.

In 2022, its team met key members of the National Heritage Board to participate in the Singapore Night Festival, as they were interested in the diversity and narrative potential of the annual arts event.

Mr Law says the tenets of modern architecture, which were drawn up in the early 20th century to respond to challenges such as housing and infrastructure, were conceived to provide solutions using mainly concrete, steel and glass.

Kampung – the Malay word for “small village” – buildings were not trying to solve climate problems.

“Kampung buildings worked with the climate and were at one with nature. The original kampung cities were very nearly net zero, and this is inspiring in the light of the current climate crisis,” Mr Law adds.

According to Prof Widodo, the primary concern today and in the future is climate change, and research has shown that the region’s vernacular architecture and settlements from the past are the best sustainability practices based on carbon neutrality.

“They used organic materials and passive design to create a comfortable microclimate without wasting anything,” he says. “We need to learn and understand the ‘DNA’ of our ancestors’ environmental, cultural, social, economic and architectural wisdom to mitigate the current crisis in our built environment.”

The Lost Cities Series: Kampong Port Cities Of Pre-Colonial Era looks at the lessons that the "kampung spirit" and its tropical architecture hold for modern designers and urban planners.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

Prof Widodo is a jury member for the Unesco Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation and a founding member and director of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (Icomos) National Committee of Singapore.

He says: “It is not about low-rise clusters or organic growth. It is about ethics and basic design principles which can be implemented in contemporary urban planning, urban design and architectural design. Singapore’s City in Nature vision and our drive towards the Green Plan 2030 are good examples of implementing Kampong Port Cities ideas.”

He says adapting to the tropical climate and a hybrid-cosmopolitan culture is the essence of social resilience, human wellness and creative innovations.

An example of implementing Kampong Port Cities principles in a contemporary structure is NUS’ SDE4 building at the College of Design and Engineering.

It features cross-ventilation, a large projected roof that provides shade and harvests rainwater, and an orientation towards the prevailing wind direction which also blocks the east-west direction of the sun.

One of the visitors at the exhibition preview on Wednesday, Mr Anupam Yog, found the interplay of tangible built structures and intangible poetry and artworks thought-provoking.

“As a placemaker who is involved in creating spaces and sparking off new ideas, I found the juxtaposition of the physicality of the exhibits and the artist’s takes on kampung culture quite inspiring,” says Mr Yog, 43, who is managing partner at XDG Labs, an experience design group, and vice-chair of the Placemaking Council at the Urban Land Institute, a global non-profit research and education organisation.

“The regenerative nature of the kampung is a source of tropical wisdom dating back to the 14th century in the region and I hope it can be preserved for future generations of designers to inform their works.”

The immersive exhibition is segmented into three facets – Past, Present and Future – with each zone serving up a slice of kampung culture that is not only relevant, but also sparks creative ways to revisit urban development.

The immersive exhibition is segmented into three facets – Past, Present and Future.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

The Past (Zone 1): Immersive Kampung Port City trek through time

The illustration at the first stop in the exhibition sets the tone with a recreation of a pre-colonial kampung dwelling called Kampong Kuala Cantik.

Here, fictional village leader “Chief Esah” guides visitors to explore a resilient society living in harmony with nature.

The region’s cities along the Strait of Malacca in the 14th century were important ports of call for cargo-laden ships on the lucrative Silk Road of the Sea that linked the East and the West, according to Professor Anthony Reid, a leading historian of South-east Asia who is known for his two-volume 1990 work, Southeast Asia In The Age Of Commerce, 1450-1680.

The port cities included Melaka in then Malaya (now Malaysia), Temasek (which was renamed Singapura and, later, Singapore) and ports in Kedah and the Indonesian province of Aceh.

Prof Reid wrote that South-east Asia was the principal source of commodities that were in great demand in the 15th and 16th centuries in the world’s markets, such as pepper, cloves, nutmeg and camphor.

The region also drew merchants from all over the world because of its sturdy tree species that flourished close to the shoreline, such as teak and dipterocarps for shipbuilding and repairs, as well as the Sunda Shelf’s rich fishing grounds.

The Oval Partnership’s Mr Chris Law says it was one of the earliest regions of international trade, where merchants from Gujarat in India, the Arabian Gulf and China brought their wares to the great coastal marketplaces.

“It was an era when wealth was created by knowledge, and networks and women were also known to have played important roles in society,” he adds.

A miniature of a kampung house recreated by miniature artist Wilfred Cheah.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

The Present (Zone 2): Kampung culture alive and well

The wrecking ball of modernisation has wiped out all traces of pre-colonial kampungs, except for two: one in Kampong Lorong Buangkok in Hougang and the other on the neighbouring island of Pulau Ubin.

While the physical landscapes of these kampungs have changed, the essence of these rustic net-zero structures – made of wood found in the vicinity and handcrafted on-site – continues to resonate with younger generations.

Ms Nicole Teh, architectural designer at The Oval Partnership in Singapore, worked with Singapore Management University students on on-site creative research workshops at Kampong Lorong Buangkok and Pulau Ubin.

“The visits and oral interviews with residents of the two kampungs were a tangible reflection of the narrative my mum shared with me about kampung life,” says the 32-year-old, whose mother lived in a kampung in the 1960s.

“There was camaraderie and trust, and residents did not lock their doors, because families welcomed neighbours who often stopped by unannounced.”

The research group found kampung architecture intriguing.

“Each element and component tells a story,” says Ms Teh. “Kampungs are renowned for their strong sense of community, tightly knit social connections and reflecting the ‘soul’ of the place, characterised by a generous expanse of public spaces.”

The group also discovered through their talks with residents that kampung houses are built through collaborative efforts among families and neighbours.

Ms Teh says: “As architects delve into the task of encapsulating the intrinsic ‘soul’ of these spaces, they might also consider looking into a participatory architectural approach that actively involves residents in the process of design, thus sculpting an environment that resonates with the collective aspirations of the community.”

The Future (Zone 3): Artists’ interpretations of the future of the urban kampung

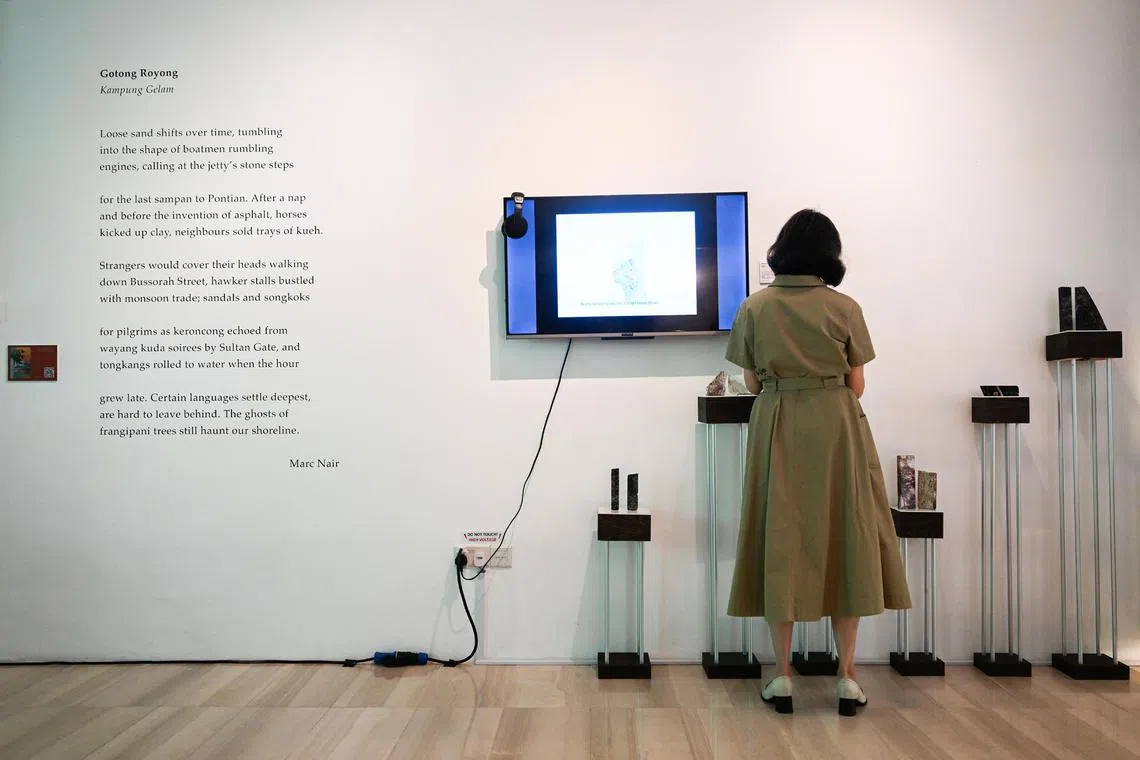

Gotong Royong Poem by Marc Nair is displayed on the wall (left) and Garden State Palimpsest by Zen Teh is on the screen in multimedia platforms at the exhibition.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

After the installations themed on the past and the present day, visitors move on to the final stage of their journey with a curated section showcasing the intangible aspects of kampung culture.

Three artists have been roped in to explore the significance of kampung culture through art and poetry, to show how it can enrich life in a bustling modern city such as Singapore.

French multidisciplinary artist Gilles Massot, whose works are based on the idea of “the space between things”, aims to establish links and decipher narratives existing between disciplines, people, occurrences and parts of the world.

His visual art practice explores the theory of photography and its relation to time and space. His works have been shown at the Singapore Art Museum and National Gallery Singapore here, and in France’s Maison Europeenne de la Photographie.

He was included in the line-up of artists by art historian Marie-Pierre Mol, a co-founder of Singapore-based Intersections Gallery, who curates a selection of Massot’s works in her online gallery.

En route to Singapore from France on Wednesday, Massot says in an e-mail interview: “Through images of local kampungs in my exhibit titled The Ulu Track, I document the evolution of Singapore together with the development of photographic technology in the last four decades, using photography techniques such as black-and-white photo processing and hand-tinting that were hallmarks of their time.”

Independent artist and educator Zen Teh, 35, who has a keen interest in subjects relating to the intersection of nature and human behaviour, explores Singapore’s constantly changing landscape and its residents’ relationship with the land through her art installation, Garden State Palimpsest.

She says: “The handcrafted photographic sculptures feature image layering on interior finishing materials such as granite and marble varieties, and are based on interpretations of interviews with former kampung dwellers.”

Marc Nair, educator, poet and multidisciplinary artist, who is also represented by Intersections Gallery, focuses on community spirit in his poem, Gotong Royong.

Educator, poet and multidisciplinary artist Marc Nair focuses on community spirit in his poem, Gotong Royong, which is featured in the exhibition.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF MARC NAIR

“Gotong royong” is Malay for “mutual assistance”, describing a voluntary act of community preservation which also refers to the kampung spirit.

Nair says the phrase has been bandied about in an effort to hark back to a more communal ethos, which is something that was lost in the wake of rapid modernisation.

His poem is a pastiche of scenes and memories of Kampong Gelam (now known as Kampong Glam) – not seen through the lens of nostalgia, but offering another way of seeing and remembering.

“The kampung represents a way of life that gives and receives in equal measure from the land,” says Nair, 41, who was the recipient of the 2016 Young Artist Award and has published 11 collections of poetry. His latest, published by Landmark Books in July, is titled The Earth In Our Bones.

He is launching a podcast series on Thursday called Estate Frequencies ( estatefrequencies.com

Nair says: “I first conceptualised this project as an homage to my housing estate. But as I wrote the script and interviewed residents for this project, I discovered instances of camaraderie, a desire for renewed community and a deep appreciation of what the estate means to people.

“And this, to me, is one way of embodying the essence of gotong royong.”

Book it / The Lost Cities Series: Kampong Port Cities of Pre-Colonial Era

Where: Fort Canning Centre, Fort Canning Park nightfestival.gov.sg/whats-on

When: Aug 18 to Oct 1

Admission: Free

Info:

Correction note: This article has been updated to reflect that the Oval Partnership has offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Singapore and London.