How a ‘forgotten’ Minnesota monastery inspired The Brutalist

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The facade of St John's Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota. The church is finding new fame as the basis for the film, The Brutalist, about an immigrant architect who is haunted by the Holocaust.

PHOTOS: AFP

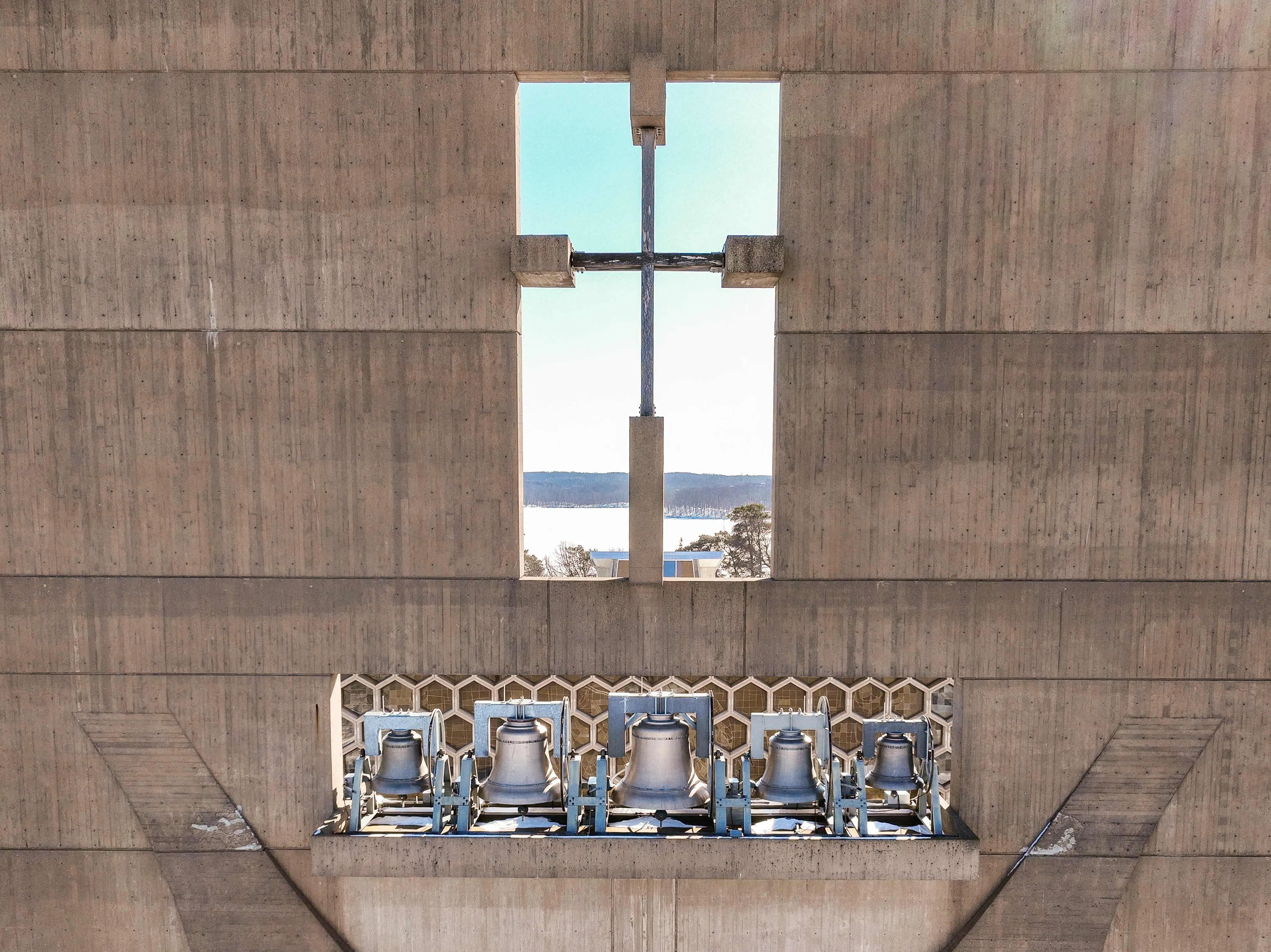

Collegeville (United States) – On a snowy prairie in Minnesota stands a monastery like no other. A concrete trapezoid banner encasing a bell tower looms over a giant, beehive-shaped front window composed of hundreds of gently shimmering hexagons.

For half a century, the existence of this modernist masterpiece in the United States has been mainly known to the Benedictine monks who worship there, and the hordes of architects who make pilgrimages to St John’s Abbey each summer.

But these days, it is finding new fame as the basis for The Brutalist, the epic drama about an immigrant architect, haunted by the Holocaust, that is a favourite to win best picture at the Oscars.

The tale of the church’s genesis is as unlikely as the movie plot it inspired, spanning titans of architecture, ambitious monks, Vatican reform – and an almighty row over that beehive window.

Monks at the daily 5pm mass at St John’s Abbey.

PHOTO: AFP

Giving tours to guests, abbey member Alan Reed begins by asking his guests: “How could this have happened?

“That this small college at the time, in the middle of nowhere, run by a group of monks, would hire a world-famous architect... It is an amazing story.”

It begins with Baldwin Dworschak, a 44-year-old “buttoned-down” abbot, who inherited stewardship of a monastery rapidly outgrowing its historic grounds in the post-war US boom years of the 1950s.

At a time when the Catholic Church was reforming and modernising, the abbot and his advisers saw an opportunity to emulate the pioneering 12th-century European monks who ushered in the then-new Gothic style.

Arranged by a monk who had studied architecture, letters inviting commissions were sent out to Richard Neutra, Walter Gropius, Eero Saarinen and Marcel Breuer – among the world’s leading modernist architects at the time.

Amazingly, several responded, and Breuer – a Hungarian Jew who had trained at Germany’s influential Bauhaus school, and invented the sleek, tubular-steel chairs that furnish trendy offices to this day – was appointed to oversee the giant church in a far northern corner of the US.

The design he came up with was “something nobody had ever seen before”, said professor of architecture Victoria Young at the University of St Thomas in Minnesota, who wrote a book on Breuer’s “extraordinary” creation.

A close-up view of the open cross and bell system on the massive concrete bell tower of St John’s Abbey.

PHOTO: AFP

Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei – a former student of Breuer’s – once wrote that St John’s Abbey would be considered one of the greatest examples of 20th-century architecture if it were located in New York, not Minnesota.

Brady Corbet, the American director of The Brutalist, cites a book written by Hilary Thimmesh, a junior member of Abbot Dworschak’s committee, as a key source for his movie.

Corbet visited St John’s and stumbled upon Thimmesh’s memoir while doing extensive reading for the film.

Several parallels are clear: a Jewish architect designing a colossal Christian edifice on a remote US hilltop, in a controversial modernist style.

A view of the honeycomb-shaped stained-glass windows at St John’s Abbey.

PHOTO: AFP

A major source of dramatic tension in the film occurs when the client – a millionaire tycoon in the movie, rather than an abbot – brings in his own designer, undermining the original architect.

In real life, Breuer struck up a friendship with Abbot Dworschak, but they fell out when the monks brought in their own stained-glass window designer, spurning the work of Breuer’s close friend and former teacher Josef Albers.

In a bitter letter, Breuer calls the move a “sudden blow” and states it would be “better to do nothing” than go ahead with the monks’ preference. The new design must be “terminated immediately”, says another letter – to no avail.

Eventually, the real-life client and architect made up.

A statue of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child is illuminated in St John’s Abbey.

PHOTO: AFP

Some inevitable Hollywood hyperbole aside, an Oscar-nominated film bringing attention to their monastery’s hidden treasure is a source of pride for those connected to St John’s.

Architect Robert McCarter wrote a book on Breuer “because I felt Breuer had been forgotten, even by the profession, to some degree”, he said.

“There are many people who think that St John’s is, by far, his greatest building. That includes me,” he said.

Prof Young agreed. “It’s still a place that enough people don’t know about.”

A baptismal font at the entrance of St John’s Abbey.

PHOTO: AFP

For the monks of St John’s today, the film could offer a more practical lifeline.

The church is badly in need of repairs, with some concrete starting to crumble and steel beginning to rust. Their order has shrunk, from being the world’s largest male Benedictine monastery with 340 monks, to fewer than 100. It is far too few for such a cavernous space.

“If we could raise enough money”, the monks could at least heat the church in winter and cool it in summer, said abbey member Reed.

And the attention the film is getting? “The monks certainly are quite impressed,” he added. AFP

The 97th Academy Awards airs live on mewatch and Channel 5 on March 3 at 8am, with a same-day repeat telecast at 9.45pm.