New book traces hawkers back to 14th-century Singapore

Sign up now: Weekly recommendations for the best eats in town

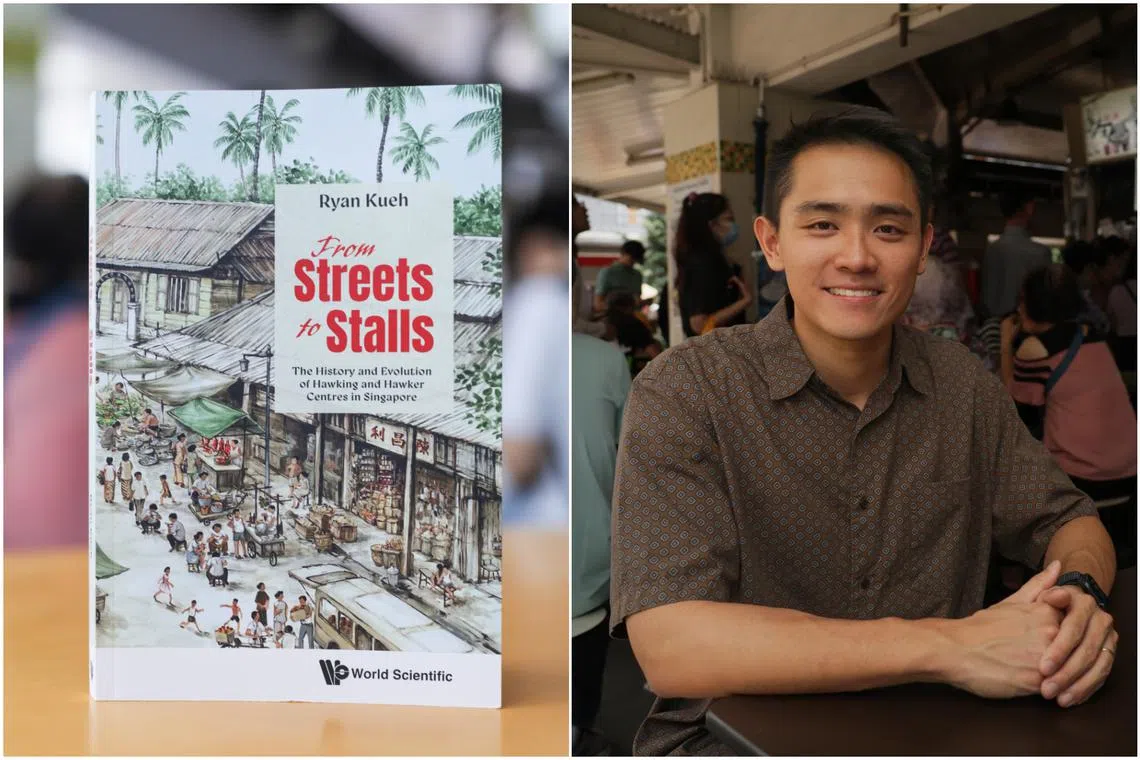

Singaporean author Ryan Kueh's 174-page book looks at the history and evolution of hawking and hawker centres here.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

SINGAPORE – Before Singapore became Singapore, in Temasek times, there were hawkers, according to a new book, From Streets To Stalls, by Singaporean author Ryan Kueh.

His 174-page book looks at the history and evolution of hawking and hawker centres here.

From research, he found that the three conditions that make it likely for hawkers to ply their trade were present at the time, when Temasek was a thriving trading hub. There was the flow of travellers and merchants coming here to trade, local artisans who were able to sell their goods and services, and currency to facilitate trading.

The 27-year-old says he was inspired to research hawker centres as a politics, philosophy, economics and history student at Yale-NUS College in early 2021.

This was just after Singapore’s hawker centres were added to Unesco’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

Kueh says: “For me, as a Singaporean who grew up in the age of hawker centres, it was quite surprising that we got the Unesco recognition over Malaysia and Thailand. I wanted to do more research into it.”

The nomination form, he adds, made the case not for street food, but for street food “performed through hawker centres”, as he puts it.

His family has ties to the hawker trade too. His maternal grandparents sold Teochew fish soup in the Serangoon area in the 1980s. His parents, who were dating at the time, helped out at the stall.

After they closed the business, his grandmother worked in a bakery in Chong Pang in Yishun, and Kueh remembers going to the hawker centre there when growing up.

From his paternal grandmother, who grew up in a pig farming village in Bah Soon Pah, he learnt about how the hawking landscape had changed over the years.

But mostly, the book, put out by World Scientific Publishing, is built on scholarly research rather than anecdotes. It looks at the proliferation of itinerant hawkers plying the trade during British rule, which led to hygiene and other lapses. Legislation and the rise of hawker shelters, proper structures with running water, were introduced to clean up the trade.

Kueh also looks at how the industry was shaped after Singapore gained independence.

Hawker centres started out being functional – places that brought order, hygiene and racial equality to the trade.

They have since evolved to become much more – places that reinforce Singapore’s standing as a multicultural and multiracial nation.

Along the way, hawker centres also became political spaces.

Kueh says: “It’s where candidates go on walkabouts or to campaign for the General Election. They turn up in a hawker centre in long pants and a shirt – they want to be seen. So hawker centres are more political than the community centre.”

Like many Singaporeans, Kueh, who will soon start work at a global management consulting firm, engages actively with hawker centres and culture.

He asks to meet this reporter at Clementi 448 Market & Food Centre because that was where he hung out as a university student. He likes the Whampoa Soya Bean stall there.

He lives in Jurong with his parents, and goes to Taman Jurong Food Centre once a week with his father for Feng Zhen Lor Mee.

Golden Mile Food Centre is where he met his wife-to-be, Ms Claudia Tan, 24, who works for a philanthropic organisation. The year was 2021, and a mutual friend introduced them over a Hokkien mee taste test there.

They will be moving into a Housing Board flat in Sin Ming near Shunfu Mart, and that is where he plans to introduce his children, if he has any, to hawker culture.

“We are so fortunate, this will be a great way to introduce them to hawker food,” he says. “Hopefully, that place will be where we can create new memories.”

Ask him what his favourite hawker food is and he says he goes around trying prawn noodle soup, adding that he likes the one at The Old Stall Hokkien Street Famous Prawn Mee at Alexandra Village. “I always make it a point to get extra prawn, pork ribs and soup,” he says.

At Jurong West 505 Market & Food Centre, he likes the chicken porridge at Soh Kee Cooked Food.

His next book project, even as he juggles work and getting married in 2025, is food-related too. He wants to look at how Singaporean Chinese and Nanyang Chinese food evolved.

The inspiration this time comes from two sources. The first is gastronaut and medical doctor Wong Chiang Yin’s 2021 book, How To Eat, which looks at hawker and Cantonese food origins, among other gastronomic subjects.

“I was struck by what he wrote, about how char siew in Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong taste different,” Kueh says.

The second inspiration comes from conversations with fellow students at Tsinghua University in Beijing, where he pursued a Master of Global Affairs degree in 2023 and 2024 as part of the Schwarzman Scholars programme.

“They had a hard time figuring out the difference between Nanyang and southern Chinese food,” he says. “That Chinese people can cook fishhead curry.”

From Streets To Stalls ($30.52) by Ryan Kueh is available from kinokuniya.com.sg