Cooking with ADHD can be overwhelming, but these cooks are finding ways to thrive

Sign up now: Weekly recommendations for the best eats in town

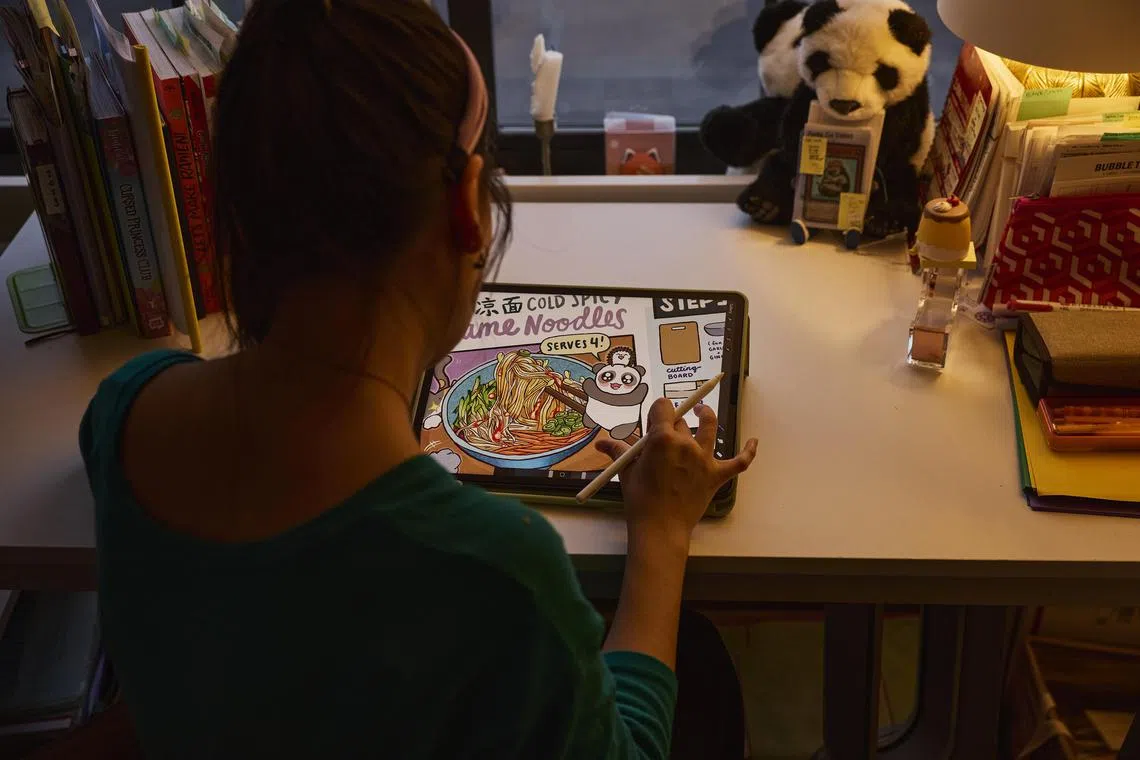

In the past, Ms Linda Yi, who has ADHD, had trouble remembering recipes and the steps to put a dish together. Now, she has turned to doodling and drawing recipes to recall better.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Follow topic:

From a young age, Ms Linda Yi was drawn to the kitchen and loved watching her parents make Sichuan dishes inspired by their native Chengdu.

But when she asked them to go over a step or recipe she had watched them make dozens of times, they would reply the same way: “You still don’t remember?”

In her mid-20s, when she became one of the 4.4 per cent of adults aged 18 to 44 diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, her relationship to cooking changed for the better.

The diagnosis helped her “see the areas of my brain that need support”, and to adapt, as many cooks with the disorder have.

For many adults, ADHD symptoms can present differently than they do in children, and in some cases, become more severe amid job, relationship and household stressors, according to the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And these challenges prove especially true in the kitchen.

One of the major issues, YouTube creator Jessica McCabe explains in her book, How To ADHD, relates to “executive function”, or the cognitive processes that tell you how to prioritise tasks, sustain attention and effectively plan for long- and short-term goals.

These play an important role whether you are shopping for ingredients or making sure your food does not overcook.

“The executive function system is like the conductor of your brain’s orchestra,” said Dr Marcy Caldwell, owner and director of the Center for ADHD, a therapy and coaching practice based in Philadelphia.

She cites cooking as being among the most complex activities calling for executive function. It can be overwhelming for her patients because it generally happens at the end of the day, when energy is depleted and medication may be wearing off.

For Ms Yi, now 34 and who lives in New York, feelings of exhaustion and frustration were intense. “It always felt like my brain was a sieve, and, as I was putting things in, things were falling out.”

Ms Linda Yi at her home in New York. ADHD, which affects executive function, can cause distinct challenges in the kitchen, leaving many to develop their own accommodations.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

She began taking notes while her parents cooked and turned those cooking instructions “into doodles with panda cubs or cats”, she said.

She posted the “doodles” on her Panda Cub Stories Instagram account in 2019 – she switched it from a personal account she started in 2011 – and gained a following, finding joy in exploring making her family’s dishes in a way that let her colourfully and playfully imbue the sights, sounds and tastes of cooking alongside written instructions.

For her, recording recipes in a creative way, instead of relying on memory, became central to helping her with executive function. Now, when she enters her kitchen with her recipe cards in tow, she prioritises working with her brain instead of against it.

She has even started Panda Cub Diner, an online cooking club focusing on Sichuan dishes.

On her YouTube channel, McCabe discusses her struggles cooking with the disorder. For example, she employs strategies to keep her from wandering off, and uses ingredients like pre-cut vegetables and frozen goods to simplify preparation work. Recipes with fewer steps and bowls to clean up and keep track of, like sheet-pan meals or slow cooker meals, are also helpful.

And, yes, she says even takeout can make the act of cooking or feeding easier, urging her followers to “lose the shame or guilt around” these tools.

“It’s not a luxury,” she said. “It’s an accommodation.”

The challenges of ADHD can also extend to chefs working in the fast-paced, high-stress environment of a professional kitchen.

As a young line cook, Spencer Horovitz, chef and owner of the dinner series Hadeem in San Francisco, often felt as if a career in the culinary field was not possible. A line cook’s work typically starts many hours before service, requiring prolonged focus, task prioritisation and time management.

“It felt like I was treading water to get to the level that it seems other cooks are starting at,” he said.

In the past, Ms Linda Yi, who has ADHD, had trouble remembering recipes and the steps to put a dish together. Now, she has turned to doodling and drawing recipes to recall better.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

While he could “laser in on a dish and replicate it a bunch”, during dinner services, he said, sustained projects such as preparing ingredients and dish components proved difficult.

Other chefs assumed he did not care about the work, and he was fired several times. “People would say, ‘You just need to try harder and muscle through it,’” Horovitz said, “and that’s just not the case.”

He realised he needed to find ways to support himself. “If I would take care of my knives, then I should take care of my body too,” he recalled telling himself.

He started taking medication, eating more healthily, prioritising sleep, limiting alcohol and drinking more water. “Just having a rubric and learning to add structure to my diet was extremely helpful,” he said.

Since focusing her work on ADHD 15 years ago, Dr Caldwell has seen a steady stream of chefs in her practice, she said. Yet she does not use prescriptive solutions.

“It’s about the process of developing your own strategies that support how your brain works,” she said. That may mean cooking alone or “body-doubling”, cooking with someone virtually to introduce accountability, as Ms Yi does in her club, and muting or turning off the camera when overstimulated. “It’s really important for people with ADHD to know their brain isn’t better or worse. It’s just different.” NYTIMES