K-pop boy band Big Ocean are making waves with sign language

Sign up now: Get tips on how to grow your career and money

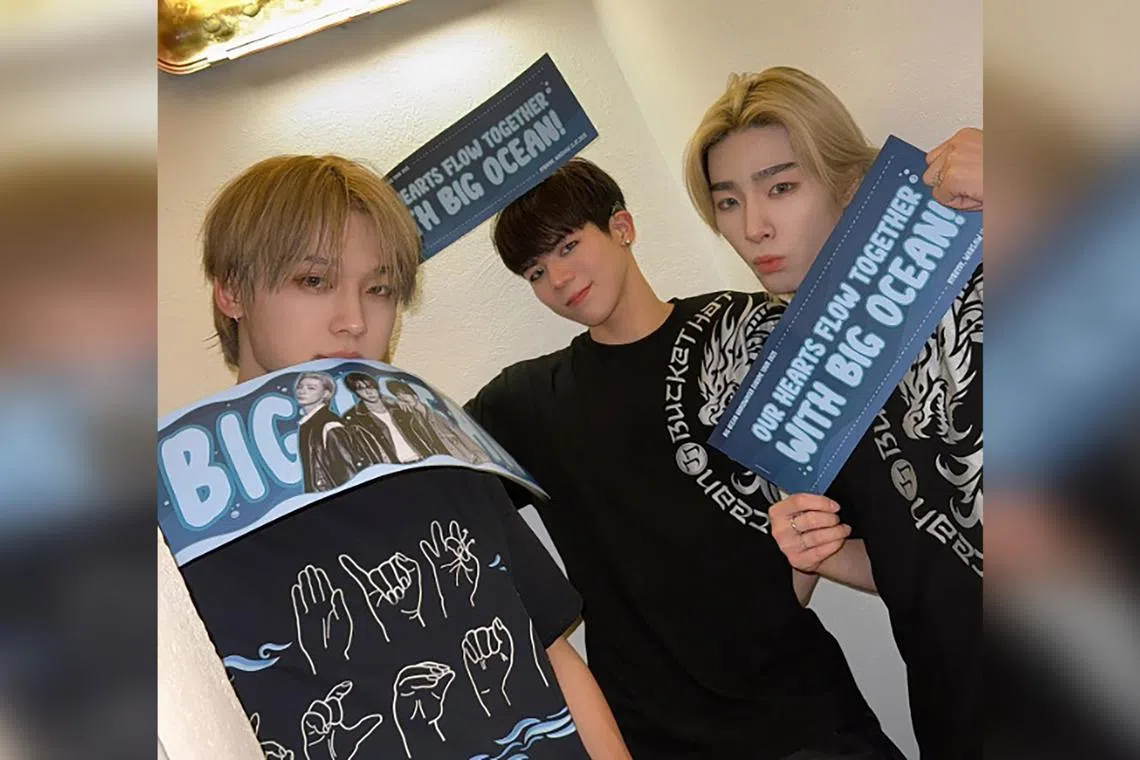

K-pop boy band Big Ocean comprise (from left) Park Hyun-jin, Lee Chan-yeon and Kim Ji-seok.

PHOTO: BIG_OCEAN.OFFICIAL/INSTAGRAM

Ephrat Livni

Follow topic:

WASHINGTON – Like other K-pop sensations, Big Ocean sing, rap, dance and attract swooning fans. But this new group’s meteoric rise is fuelled by a skill it seems no other boy band boasts: signing.

The band members – Lee Chan-yeon, 27; Park Hyun-jin, 25; and Kim Ji-seok, 22 – are all deaf or hard of hearing. They use the latest audio technology to help make their music, coordinate their choreography with flashing metronomes and vibrating watches, and incorporate Korean Sign Language (KSL) into videos and performances.

“Just like divers rely on signs to communicate underwater, we use sign language to convey meaning where sound alone might fall short,” Lee said. “For us, KSL is not just an element – it’s the heart of our performance.”

The group released their debut single Glow in 2024, on Korea’s Day of People with Disabilities, and they did their first televised performance incorporating KSL, generating local buzz that reverberated beyond national borders. Soon after, they followed up with Blow, a single heavy on English lyrics and American Sign Language.

In September 2024, they were named Billboard’s rookies of the month. And recently, they made the Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia Entertainment & Sports List.

In July, the band performed at an anime festival in Brazil and a United Nations tech event in Switzerland, before touring Europe for the second time since spring. Their first American tour starts later in July.

Big Ocean now have 997,000 followers on Instagram and more than 696,000 on TikTok. Fans, who call themselves “Pados” after the Korean word for wave, are devoted, and many are learning sign languages from the band, who make numerous tutorials.

But fame was never assured, said Ms Haley Cha, chief executive of Parastar Entertainment, Big Ocean’s management company. “We had many difficulties in developing this band,” she added.

Even the members sometimes questioned their dream, she said. They had alternate careers, and it was not always clear to them or to others what they could achieve in music.

Park, who goes by P.J., was a YouTuber, creating content about hearing disabilities. Lee worked as an audiologist at a hospital. Kim had been an alpine skier.

Ms Cha said she used a variety of tactics to help them visualise stardom, including taking images of established K-pop idols and replacing the faces with those of the trio. They have since made videos and performed with industry luminaries.

A major breakthrough

Big Ocean’s rise did not happen in a vacuum. The band’s struggles and successes reflect broader advances for South Korea’s deaf community, nearly a decade after the country recognised KSL as an official language, distinct from spoken Korean.

About a quarter of a million South Koreans are deaf or hard of hearing. An estimated 84 per cent of them use sign language as a primary mode of communication, and more than one-third live in the capital, Seoul.

Historically, there were few educational opportunities for the deaf community, and there was little recognition of KSL, said Mr Jeonghwan Kim, president of the Seoul Association of the Deaf.

A national association for the deaf was established in 1946, but the emphasis on education during much of the 20th century was on speech training rather than signing.

That focus on speech in South Korea was part of a wider global trend that was hotly debated, particularly with the development of cochlear implants to aid hearing. Some argue that sign language as an expression of deaf culture and identity is marginalised when speech is emphasised.

Big Ocean blend singing with signing, and the path for South Korea’s embrace of the band was paved with legislation.

In 2016, the Korean Sign Language Act went into effect, recognising KSL as the official language of the deaf community. It was “a major breakthrough”, Mr Kim said, adding that it marked a substantial step forward in securing their “linguistic rights and cultural identity”.

The National Institute of Korean Language began working to promote KSL and develop educational materials, conducting research on sign language usage, building a dictionary and training instructors, according to Ms Hyesun Chung, a research officer in charge of KSL at the institute.

The institute has also tried to promote the idea “that deaf people have the right to enjoy and express their culture through their own language”, she said.

Those institutional changes have helped shift cultural views, leading to the acceptance of deaf artistes, including Big Ocean. The band, in turn, have raised awareness of deaf culture in South Korea and the world.

“Many deaf youth see their presence onstage as a powerful form of representation,” Mr Kim said. “Their work broadens the public’s perception of artistic expression beyond sound.”

Global reach

Big Ocean wanted to make waves worldwide, so the group studied ASL and International Sign (IS) to create shows that were more accessible across different cultures. “When fans sign back during concerts, it’s one of the most powerful forms of connection,” Kim Ji-seok said.

Fans do sign back, online and at performances, and the band’s emphasis on signing has helped to educate people about a basic fact: Every sign language is distinct from the corresponding spoken tongue, as well as from other sign languages.

For followers already in the know, Big Ocean’s use of sign language is extremely gratifying.

Responding to a recent IS video tutorial for the song Sinking, one commenter with hearing loss wrote: “Been blasting this through my headphones and emotionally signing it all night.”

For their part, the trio’s members seem delighted that they inspire people and are heartened by the world’s response. “Knowing that our music resonates with Pados worldwide motivates us to keep pushing boundaries,” Park said.

Lee noted that at a recent meeting, they met fans “who were overcoming cancer, surviving school bullying or healing from personal hardships” and who felt inspired by their work.

“One fan told us, ‘You’re proof that something that seems impossible can actually happen,’” he said. “That moment really stayed with me.” NYTIMES