At The Movies

Obsessive love gets a bold, modern makeover in Wuthering Heights

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

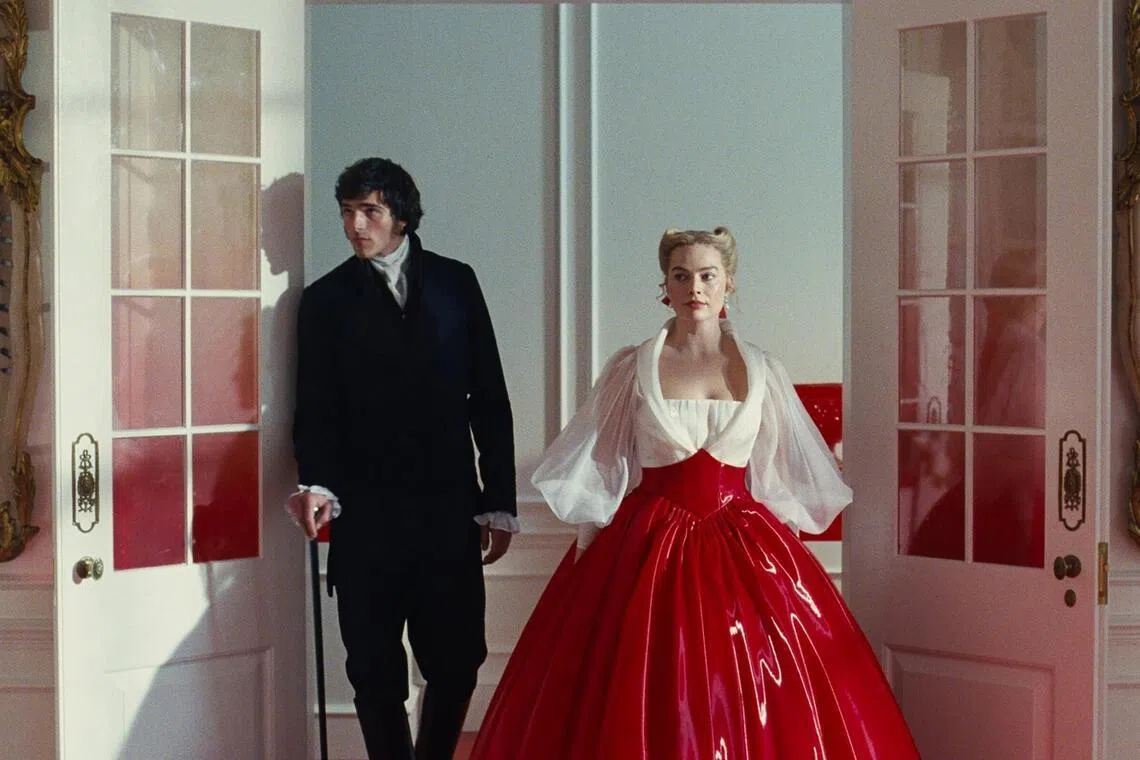

Margot Robbie (left) and Jacob Elordi in Wuthering Heights.

PHOTO: WBEI

Wuthering Heights (M18)

136 minutes, opens on Feb 12

★★★★☆

The story: The already struggling Earnshaw family is further burdened when Mr Earnshaw (Martin Clunes) adopts a homeless child. His daughter Catherine names him Heathcliff, after her dead brother. As they grow older, so does their affection for each other, but the class gap is unbridgeable. Wealthy new neighbour Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif) enters the picture, driving a wedge between Catherine (Margot Robbie) and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi).

English film-maker Emerald Fennell’s previous two films, the revenge drama Promising Young Woman (2020) and thriller Saltburn (2023), dealt with love and sex as games of domination.

Her focus remains unchanged in Wuthering Heights, despite it being her first adaptation of an existing work. She – pardon the pun – strips English author Emily Bronte’s 1847 novel of the same name to its bare components. The sexual drama between Catherine and Heathcliff now takes centre stage.

Fennell has gained a reputation as a feminist iconoclast smashing cinematic tropes created by men, but she ought to be as celebrated for her skills in visual storytelling. Early scenes with Catherine as a child (played by Charlotte Mellington) reveal volumes about her character with much dialogue, making the adult easier to forgive.

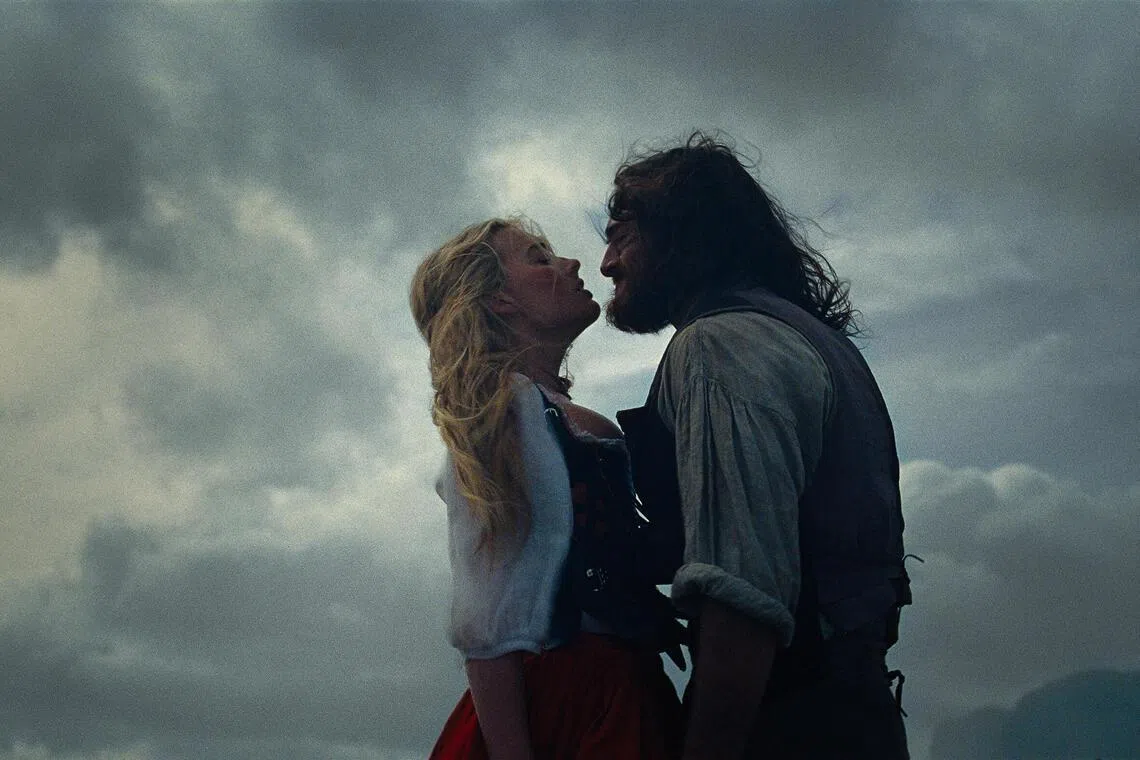

Jacob Elordi (left) and Margot Robbie in Wuthering Heights.

PHOTO: WBEI

And forgiveness is key. Robbie’s grown-up Catherine is a complicated mix of abiding kindness and shocking cruelty. Fennell, as in her previous films, dares viewers to not only like this unlikeable person, but also to fall in love with her, to tag along as Catherine figures out what she wants and how she must get it.

Elordi’s Heathcliff is mostly unknowable, but that is on purpose. In this story, his mysterious aura is reinforced at several points, adding to his allure.

The Australian actor’s physical presence – exposed in all its rippling glory in a couple of scenes – is crucial to the story. Fennell uses top-down lighting to outline the deep brow ridges, keeping Elordi’s eyes shadowed, emphasising his primal, dangerous nature.

The synth-heavy score of English composer Anthony Willis (who also worked on Promising Young Woman and Saltburn) and the pop of English singer Charli XCX underline Fennell’s modern take on obsessive love. Catherine and Heathcliff exist in the 19th century, so Catherine’s feelings of shame, guilt and disgust are amplified.

Fennell has fun imagining how people with money during that period might self-therapise, and this is where the story enters the psychological and symbolic terrain explored in films like Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999) or Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden (2016). Fennell, however, does it her way.

Oh, the games upper-class English people play. Her images might be confronting, even disturbing, but – without showing much skin – are undeniably erotic.

Hot take: Fennell’s visually striking, psychologically intense adaptation of the novel has a bold, modern sensibility.