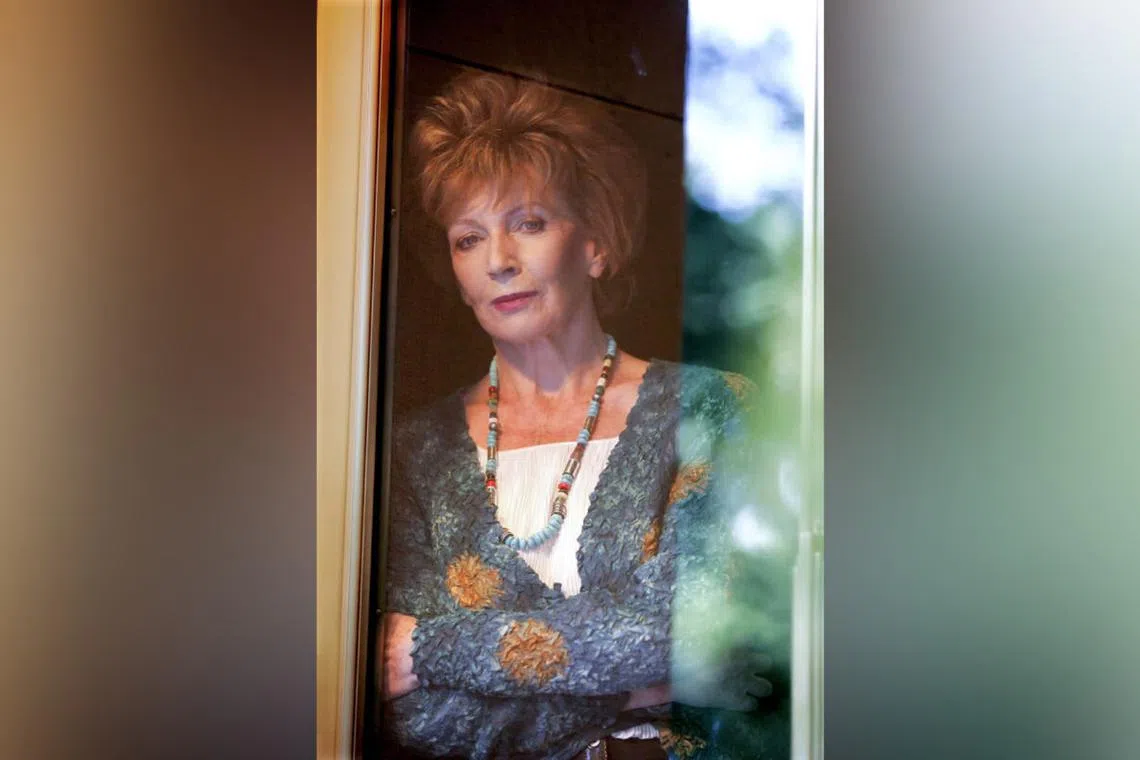

Irish author Edna O’Brien, writer who gave voice to women’s passions, dies at 93

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Edna O'Brien had spoken in recent years about being treated for cancer.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Follow topic:

NEW YORK – Edna O’Brien, the prolific Irish author whose evocative and explicit stories of loves lost earned her a literary reputation that matched the darkly complex lives of her tragic heroines, died on July 27. She was 93.

Her death was announced on social media by her publisher, Faber, which said only that she had died “after a long illness”. She had spoken in recent years about being treated for cancer.

O’Brien wrote dozens of novels and short-story collections over almost 60 years, starting in 1960 with The Country Girls, a book that dealt with the emotional conflicts of two Irish girls who rebel against their Roman Catholic upbringing.

Her books often depicted wilful but insecure women who loved men who were crass, unfaithful or already married. Much of her early work carried aspects of autobiography, which stirred whisperings about her morals and led to personal attacks against her back home in Ireland.

When her writing was first published, she was considered a literary pioneer whose distinctive style gave voice to women whose passions had never been portrayed with such honesty.

“I learnt from her,” American novelist Mary Gordon once said, “particularly her way of writing about the intensity and danger of childhood. She has described a kind of girl’s life that hadn’t been talked about before.”

But the boldness of her writing never endeared her to the women’s rights movement, which disliked her evocation of hard-luck singles and desperate mistresses. O’Brien took the rejection in stride.

“I don’t feel strongly about the things they feel strongly about,” she once said, referring to women’s rights advocates. “I feel strongly about childhood, truth or lies, and the real expression of feeling.”

For decades, her work was more highly praised outside Ireland than in her homeland, which she left for good in the 1960s. With her auburn hair, green eyes and Irish country lilt, she was seen by non-Irish critics as the embodiment of Ireland itself. But in Ireland, her persona struck many as too rich to be real. (The Irish literary critic Denis Donoghue called her “stage Irish.”)

Her work eventually won over many critics. In 2001, she received the Irish PEN lifetime achievement award, and in 2018, the PEN/Nabokov award for achievement in international literature.

But the early criticism left lasting marks. The Country Girls had shamed her conservative Roman Catholic parents in rural western Ireland. The book’s descriptions of the girls’ sexual escapades appalled many, and with the approval of the Catholic Church hierarchy the book was banned in Ireland, as were several subsequent ones.

The book was dedicated to O’Brien’s mother, but “my parents were too ashamed to be proud” and never recovered from the hurt, she said. After her mother died, O’Brien found a copy of The Country Girls that she had given her years before. The dedication page had been torn out, and offensive words had been blotted out with a pen.

But readers, particularly women, and critics in other countries, especially in the United States and Britain, found her work compelling, touching and truthful. She acquired a reputation as a woman given to frequent love affairs, but she maintained that having lovers did not make her promiscuous.

“I believe in love, not promiscuity, and they don’t go together,” she said in a 1995 New York Times interview. “I am a romantic. We’re very wise in our minds, but in our hearts, we’re very turbulent.”

Most of all, O’Brien felt she should be judged on her writing, which could be crisp, intense and risky, or overwrought, indistinct and worthy of a Hallmark card. Some of her strongest efforts came when she used the banality of rural life to explore deep emotions.

In House Of Splendid Isolation (1994), she wrote: “I think of the rows, rows over money, my husband putting on his cap to go out and escape from me, a black greasy cap that his ire had sweated into, bacon and cabbage, the dogs yelping for the leavings, downpours and in spite of it all there used to be inside me this river, an expectation for something marvelous. When did I lose it? When did it go? I want before I die to be myself again.”

Josephine Edna O’Brien was born on Dec 15, 1930. (She once told an interviewer, “If I die and you write my obituary, don’t give my age.”) Her parents, Michael and Lena (Cleary) O’Brien, lived on a farm in Tuamgraney, a rural hamlet in County Clare that O’Brien described as “a very frightening and arrestive place”.

Although she had three siblings, she was a solitary child who wandered through the woods near her home, dreaming up stories and filling copybooks with her tales. In 1941, she entered the Convent of Mercy in Loughrea, County Galway, intending to become a nun. She stayed five years before going to Dublin, where she worked in a pharmacy.

In Dublin, O’Brien read widely and began submitting short stories to newspaper competitions, encouraged by Czech-Irish novelist Ernest Gebler. Rebelling against the strictures of their rural community, they eloped in the early 1950s. The marriage did not last and, after their divorce, O’Brien took their two sons with her to London.

Gebler died in 1998. O’Brien’s survivors include her sons Sasha, an architect, and Carlo, a writer, along with several grandchildren. NYTIMES