Donald Sutherland didn’t disappear into roles, and that was a good thing

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

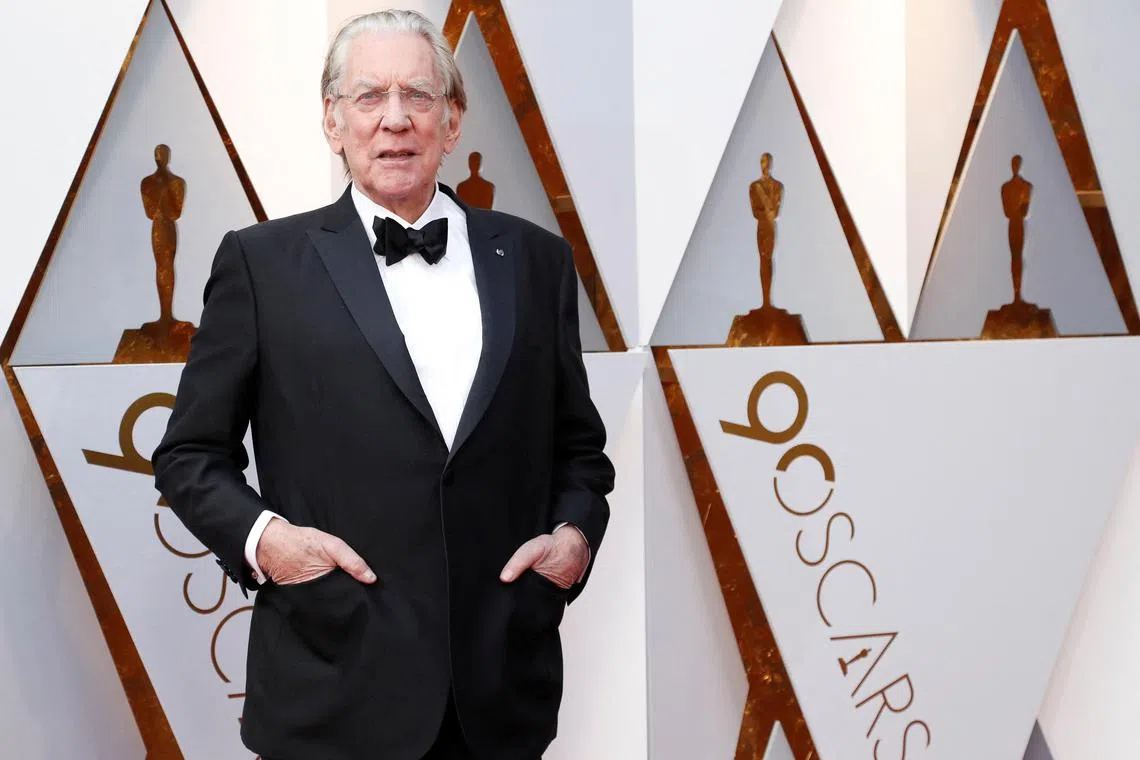

Actor Donald Sutherland worked constantly and, unlike some actors of his generation, never really seemed like he belonged to a single era.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Alissa Wilkinson

Follow topic:

NEW YORK – In a 2014 interview in GQ, Canadian actor Donald Sutherland recalled that a movie producer told him he was not getting a role he had auditioned for.

This was because “we’ve always thought of this as a guy-next-door sort of character, and we don’t think you look like you’ve ever lived next door to anybody”.

It is true. In film and TV roles that stretched over 60 years, Sutherland, who died on June 20 at age 88, never radiated the sense that he was some random guy you might cross paths with at the grocery store. If you did, you would remember him, maybe a little uneasily.

With a long face, piercing blue eyes, perpetually curled upper lip and arched, wary eyebrows, he had the look of someone who knew something important – a useful characteristic in a career that often involved movies about paranoia and dark secrets.

His voice could clear a range from excitedly high to a menacing bass that would make you feel like ducking for cover.

As an actor, he could do it all. His turn as the titular private detective opposite Jane Fonda in Alan Pakula’s 1971 Klute rides a tricky knife’s edge. Is he a good guy? Does that term have meaning in this case?

There was his role as a slowly more horrified scientist in Philip Kaufman’s 1978 Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, and his movie-stealing monologue as Mr X in Oliver Stone’s 1991 JFK, loaded with the urgency of obsession.

Even when playing a goofball – the womanising prankster surgeon Hawkeye Pierce in Robert Altman’s 1970 M*A*S*H, for instance, or Vernon L. Pinkley in Robert Aldrich’s 1967 The Dirty Dozen – his loping, laconic figure stood out against the background, someone who knew a little better than he let on.

Sutherland worked constantly and, unlike some actors of his generation, never really seemed like he belonged to a single era.

He had already been at it for more than 40 years when he showed up in Joe Wright’s 2005 Pride And Prejudice, in what seemed like a minor part: Mr Bennet, put-upon father to five daughters in yet another adaptation of Jane Austen’s novel.

In the book, Mr Bennet is sardonic and contemptuous of all but his oldest two daughters, Jane and Lizzy. The reader does not walk away with particularly warm feelings about him.

But Sutherland’s version of Mr Bennet was a revelation, without being a deviation. In a scene granting Lizzy (Keira Knightley) his blessing to marry her beloved Mr Darcy, tears sparkle in his eyes, which radiate both love and, crucially, respect for his headstrong daughter.

Suddenly this father was not just a character, but a person – a man who can see his daughter’s future in a moment and is almost as overcome as she is.

That movie does not represent the start of a Sutherland-aissance, since his career did not need reviving. But his early performances had been set in an age when institutions were not to be trusted, and movies were suspicious of anyone in power.

Sutherland himself had been on a National Security Agency watch list from 1971 to 1973, at the request of the FBI, thanks to his anti-war activism. He seemed to never lose his interest in confronting power.

So the role of President Coriolanus Snow, the antagonist in the deeply paranoid Hunger Games movies (2012 to 15), was a natural fit – and he thought so, too.

In the GQ interview, he said he had not been offered the role, but when he read the script for the first film, it “captured my passion”. At the time, he said, Snow had only a couple of lines, but “I thought it was an incredibly important film, and I wanted to be a part of it”.

He wrote a letter to director Gary Ross, expressing his passion for the project.

“Power,” it began. “That’s what this is about? Yes? Power and the forces that are manipulated by the powerful men and bureaucracies trying to maintain control and possession of that power?”

Later, he noted that Snow was, “quite probably, a brilliant man who’s succumbed to the siren song of power”.

Near the end of the letter, he noted that Snow did not look evil to the wealthy citizens of his world’s capital city, but that “Snow’s evil shows up in the form of the complacently confident threat that’s ever present in his eyes. His resolute stillness”.

In The Hunger Games films, that stillness is evident. There is very little sense of menace in Snow, as interpreted through Sutherland.

He is the sort of person whom someone like Katniss, the young woman caught in a whirlwind of events she both understands and wishes she did not have to understand, hopes she could trust.

It is Sutherland’s voice as much as his expression that gives that impression, perhaps because, as the actor understood, he is not a cardboard cut-out authoritarian.

He is an encapsulation of the idea that power, once grasped, is hard to let go of. The humanity that occasionally shines through Sutherland’s eyes as Snow makes it all the more heartbreaking.

The long list of Sutherland’s roles and accomplishments shows a man who understood emotion well. But it is this marriage of suspicion and empathy, human feeling and the fear of humanity gone wrong, that secured his place in acting history and made him an uncommon kind of star.

He did not disappear into a role, not exactly. He was too distinctive for that.

More often, the role disappeared into him, and the result was something unforgettable. NYTIMES