At The Movies: The Boy And The Heron finds Hayao Miyazaki looking back, fondly

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

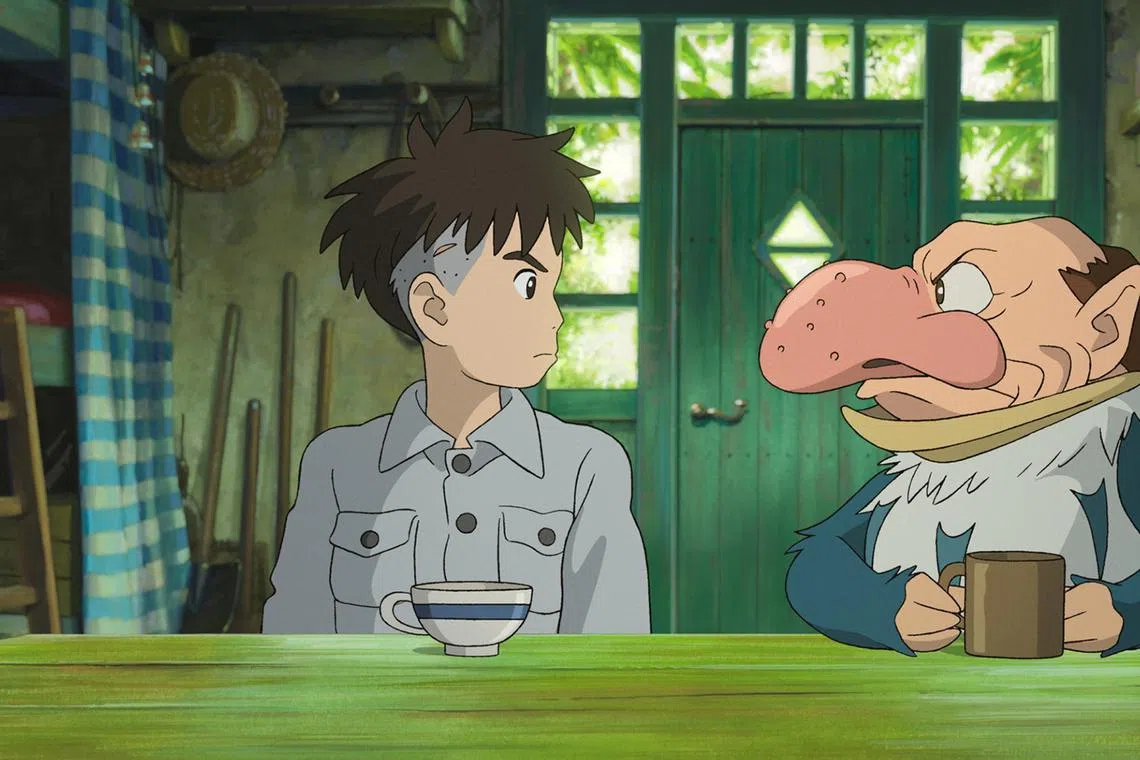

The Boy And The Heron is the latest film from Japanese animation master Hayao Miyazaki.

PHOTO: STUDIO GHIBLI

Follow topic:

The Boy And The Heron (PG13)

124 minutes, opens on Nov 30

4 stars

The story: Japan is in the midst of World War II. Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki) is an 11-year-old boy whose mother has died in an American air raid. His factory boss father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura) moves his family to the countryside. There, at a large estate, the boy meets his aunt-turned-stepmother Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura). The resident heron, normally a stand-offish bird, begins intruding into the family rooms, bringing a strange message about his dead mother. The boy’s curiosity draws him into a world of wonder and terror.

This semi-autobiographical story is based on Japanese writer-director Hayao Miyazaki’s wartime evacuation from the city to the countryside.

The revered maker of animation classics, most of them made under his Studio Ghibli banner, visits many of his favourite themes – adults who have lost the ability to dream are useless, a tissue-thin door separates the natural and supernatural realms, scary demons are only misunderstood people and fighting skill alone will never get a kid out of trouble.

For a kid to find his way home, it takes courage, imagination – and this is something you will rarely find in Western fantasy stories – and the willingness to put in hard work.

Mahito, like Chihiro in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001), is the main character and offers the only point of view.

The grown-ups around him do odd things. His widower father, for instance, marries another woman, as if his mother had been forgotten. No one wants to talk about the weird events happening around the old country home, least of all the elderly maids who look after him.

Older people are, of course, a Miyazaki staple – they carry wisdom. But more importantly, they are the conduits of habits no longer found in modern urbanised Japan.

The maids do plenty of cooking and the serving of food, which Miyazaki lovingly documents with close-ups. When the women get a gift of sweets – a rare treat during wartime – the film pauses to show their joy in eating them. The women display the same eagerness for tobacco.

In fact, the economies of the natural and supernatural worlds are filled in. Miyazaki illustrates the flow of goods both within the realms and between them. It is a trait that makes his stories complete and satisfying. Trade, not magic, is how things get done.

Mahito, like Chihiro in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001), is the main character and offers the only point of view.

PHOTO: STUDIO GHIBLI

Mahito’s father makes fighter plane parts. Workers are shown moving them here and there; it is how he can afford his lifestyle. For Miyazaki’s young protagonists, zapping problems with magic is rarely the solution. Tight situations are fixed when kids stop fretting about their needs and start thinking about the desires of others.

The visuals might not be as gorgeously complex and detailed as the frames of Spirited Away or Princess Mononoke (1997) – this work has a smaller, more intimate feel to it. It is Miyazaki looking at his childhood through a magical lens, after all.

Hot take: Animation master Miyazaki’s latest film is an enjoyable trip down memory lane, following a boy lost in a rustic Japan filled with hungry spirits and magical fisherfolk.