At The Movies: Godzilla Minus One makes monsters scary again

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

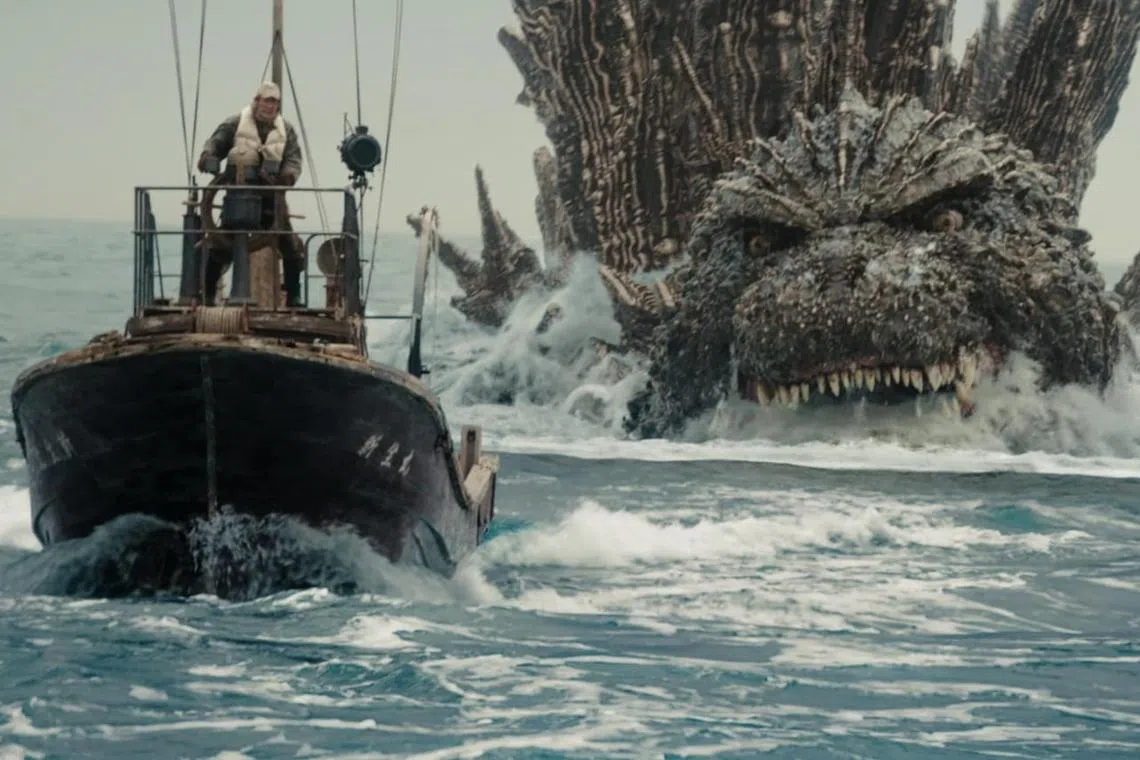

For aquatic scares, Godzilla Minus One takes inspiration from Jaws (1975).

PHOTO: TOHO

Godzilla Minus One (PG13)

125 minutes, available on Netflix

4 stars

The story: After World War II, Japanese pilot Koichi (Ryunosuke Kamiki) is physically unharmed, but traumatised by an incident on a remote island involving a beast the locals call Godzilla. He returns to a shattered Tokyo, with both parents killed by an air raid and starvation looming. Even as he tries to put his past behind him with fellow survivor Noriko (Minami Hamabe) and an orphaned baby, the creature he thought he left behind returns to threaten everyone he loves.

It has been a long wait, but here it is at last, on Netflix. This Oscar-winning creature feature opened in overseas cinemas last year, meeting with critical and commercial success, but was unavailable in Singapore because in certain regions, two Godzilla movies cannot be released at the same time.

This modest Japanese production costing US$12 million (S$16 million) had to give way to Hollywood’s Godzilla X Kong: The New Empire (2024), which cost 10 times more to make.

Godzilla Minus One, winner in the Best Visual Effects category at the 2024 Academy Awards, puts in what the American product leaves out: The monster being monstrous.

Taking cues from Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Jurassic Park (1993), Japanese writer-director Takashi Yamazaki draws scares from the title character’s ability to lurk beneath the waves, striking suddenly from the depths.

On land, the beast – Tyrannosaurus-sized in the first chapter – puts its teeth to work on human bodies. When it grows to skyscraper heights, the feet and tail squash people like bugs. The computer-generated images of mayhem are sharp and packed with detail, a departure from Hollywood’s current obsession with murky battle scenes.

The story does not attempt to give the monster a sense of purpose. There are no thoughts behind the eyes, only animal aggression. Contrast this with the current American versions, which try to Marvel-ise the story so it fits within a Monsterverse, resulting in movies bogged down with exposition, introductions and spin-off lead-ins.

The story also could not be simpler, or more Japanese.

The disgraced Koichi represents a post-war Japan burdened with the shame of defeat. But through self-sacrifice, resilience and teaming up with people who believe in him, his arc goes from tragic to triumphant. American heroes rise because they are blessed with talent; Japanese characters become heroes because they try harder than anyone else.

Godzilla is nature, ferocious and unknowable. The previous Japanese production Shin Godzilla (2016) took the form of political satire, with officials more concerned about saving their jobs than with saving lives in the face of impending disaster.

In Godzilla Minus One, the line “the monster is our problem, we will have to save ourselves” is said a couple of times. In a land beset by tsunamis, earthquakes and nuclear accidents, it is a phrase heavy with meaning.

Hot take: This love letter to ordinary Japanese citizens who pull together to get the country out of hard times succeeds in delivering genuine emotion along with monster action.